The first in a semi-regular series that breaks down a poem to analyse what it’s really trying to tell us.

When it works, a poem is like a lightning bolt: it can illuminate an idea with an otherworldly clarity making it both true and strange at the same time. A poem can cause your heart to rise up your throat; can turn an idea around to face you and reflect your own self back. Startling stuff.

The poem has an extremely long and illustrious history: bridging class, politics, culture, even art forms. Performance poetry, in particular, has long been a community event and a medium for the people. There’s a fine line, at times, between performance poetry and music gigs, and poets and musicians (think Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for literature). The commonality between them being words (and through them images, stories, ideas) offered up with voice, craft and intention to a waiting audience who have both private and public reactions. There’s a musicality to poetry: when you listen to it read aloud there’s rhythm, patterns, major falls and minor lifts.

But what about on the page? Poetry in our heads? How many of us regularly read a poem and have our private way with it? It’s hard to say. The publishing of poetry is, for now, healthy in Aotearoa: we have a number of dedicated journals and publishers who ensure that we have new singles, collections and anthologies each year.

Still, a poem can appear like a trickster: tangly, even daunting. This series is intended to de-mystify poetry on the page and arm the reader with some tools to help find your way into them, no matter how freaky the poem might seem at first glance. We’ll go through some iconic poems and make our way to some contemporary hits. We’ll occasionally look at particularly poetic song lyrics, too.

First in this series is Waterfall by Lauris Edmond, published in 1975 in her first collection In Middle Air. It’s a poem about time and love as observed through the lens of nature. An extremely brief summary of Lauris Edmond OBE includes: born in Dannevirke in 1926 and died in Wellington 2000. In Middle Air was published when she was 51 years old and it won the PEN first book award. After that Edmond continued to publish and win many awards and is now considered one of our most successful poets (and novelist – her first book, High Country Weather, about an unhappy marriage is a celebrated feminist text).

Waterfall by Lauris Edmond

I do not ask for youth, nor for delay

in the rising of time’s irreversible river

that takes the jewelled arc of the waterfall

in which I glimpse, minute by glinting minute,

all that I have and all I am always losing

as sunlight lights each drop fast, fast falling.

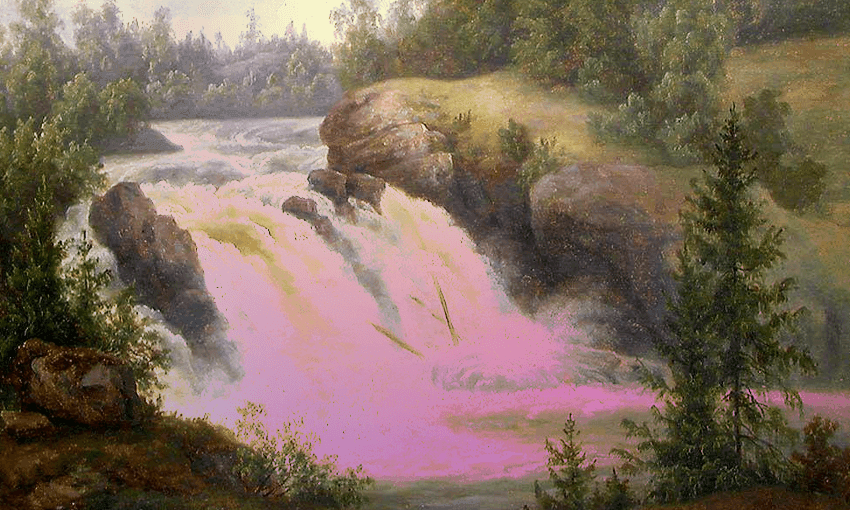

Reading notes: First, the title. We can all, I think, conjure a lush, gushing waterfall in our minds. The way a river is interrupted by the loud torrent, the sparkle of spray. When you think about it, waterfalls are everywhere in art, from the steamily romantic, to the action movie, to the landscape painting dripping with shadows and thick, oily paint. It’s an active image that will bring up different things for everyone, but a waterfall is also a shared image: we have a collective understanding of its basic elements.

The first stanza isn’t quite a request but there is, immediately, an idea of an impossible ask: “I do not ask for youth, nor for delay / in the rising of time’s irreversible river”. The poet is thinking of time as a river. The way it moves and rushes on by. They way it can exist and be lost at the same time. It’s a beautiful metaphor that turns our minds to the way that nature holds a truth about entropy (the process of breaking down), and life cycles, and time not really being linear at all.

The poet looks at the “jewelled arc of the waterfall” which is a reference to the drops of water that glisten in the sun. You could think of this as like looking at the fragments of life that sparkle in among the torrent and rush. This final fragment – “as sunlight lights each drop fast, fast falling” – uses repetition: “light” is there twice and so is “fast, fast”. This is gorgeous but devastating. Light is like magic (so fast it’s hard to understand), just like life can be magic (at times), but also so very fast, fast.

I do not dream that you, young again,

might come to me darkly in love’s green darkness

where the dust of the bracken spices the air

moss, crushed, gives out an astringent sweetness

and water holds our reflections

motionless, as if for ever.

Here we have the repetition of that “I do not…” which really asks us to suppose that really, they do. Or, they wish they could. That second line, “might come to me darkly in love’s green darkness” is extraordinarily evocative and plays with the imagery we might call up when we think about a waterfall. Later on there’s the word “moss” which perfectly sums up a “green darkness”. It’s interesting that the poet has repeated “dark”. Do we think of love as dark? Memories certainly can be: they can be like shadows. But the image continues with “where the dust of the bracken spices the air / moss, crushed, gives out an astringent sweetness”. This detail, the breaking down of the image into small parts, is designed to awaken our senses: taste (“astringent sweetness”) and smell (“spices the air”). This suggests that while love has the feeling of darkness, there is so much more to it. The stanza (word for a paragraph in a poem) returns to the water and the idea that nature can mirror life back to us: “water holds our reflections / motionless, as if for ever.”

I’m really fascinated by the decision to turn forever into two words – for ever. It suggests that the reflection serves an “ever”. It is a cunning fallacy: a motionless reflection will never be there forever, or at any time. It’ll only be there when you’re there to meet it.

It is enough now to come into a room

and find the kindness we have for each other

— calling it love — in eyes that are shrewd

but trustful still, face chastened by years

of careful judgement; to sit in the afternoons

in mild conversation, without nostalgia.

This stanza is a break in the waterfall image. We’re now in a “room”. We’ve entered the present (“now”) and the domestic. In this piece of time (the now) love has turned into “kindness”. There’s been a shift in the relationship: “eyes that are shrewd / but trustful still, face chastened by years / of careful judgement”. Time has caused something like a chemical reaction: love has transformed into something else. The words “eyes, “shrewd”, “trustful still” and “careful judgement” all suggest a deep knowing. The phrase “face chastened by years / of careful judgement” is an interesting one. There’s the idea of aging, but also that the relationship has changed the look of someone, the expressions they hold on their faces, the way they react to each other. The final lines, “to sit in the afternoons / in mild conversation, without nostalgia” is gentle, slow and makes you think of a certain kind of content. The connection isn’t passionate or racy at this point but being together isn’t hard and they’re not trying to be something that’s gone by (“without nostalgia”).

But when you leave me, with your jauntiness

sinewed by resolution more than strength

— suddenly then I love you with a quick

intensity, remembering that water,

however luminous and grand, falls fast

and only once to the dark pool below.

Aw. This is like a twist to the heart string. What does “when you leave me” really refer to? It could be the daily leaving of simply exiting a room or the house. But it might also refer to the end of life. The phrase “with your jauntiness” makes this idea even more poignant: you would miss someone who is jaunty (doesn’t it make you think of things like charm, bubbly, optimism, joy?). This idea is compounded by the second line: “sinewed by resolution more than strength”. This asks you to consider that the person doing the leaving might well be older, that the body might not support jauntiness like it once did, but the mind of this person is still resolved to embody that chirpy state.

The final four lines take us full circle, back to the waterfall and its symbol of fleeting passion. “Suddenly then I love with with a quick / intensity”. That’s it! A waterfall is a quick intensity (orgasmic, even). The line falls quickly down to the idea of brevity. The phrase “however luminous and grand” suggests something that is robust and heavy and timeless. But of course in this case it’s not. A waterfall “falls fast / and only once to the dark pool below.”

What a stunning way to leave us: to remind us that life is short. What happens after the rush is unknown (“dark”) and we only get one shot at it.

Does it make you want to look, shrewdly, at the people you love? Does it make you sad and thrilled at the same time? Will you ever look at a waterfall in the same way again? Thanks to Lauris Edmond, hopefully not.