Floods

Where are people and land at risk from flooding?

Data essay by Chris McDowall

Aotearoa is a steep and rugged country. Our settlements are concentrated in pockets of fertile floodplains, around river mouths or along coastlines. During the last few decades, these places have experienced increased river and coastal flooding. As sea levels rise and weather patterns change in response to climate change, floods are forecast to become both more frequent and more severe.

Rivers are wild things

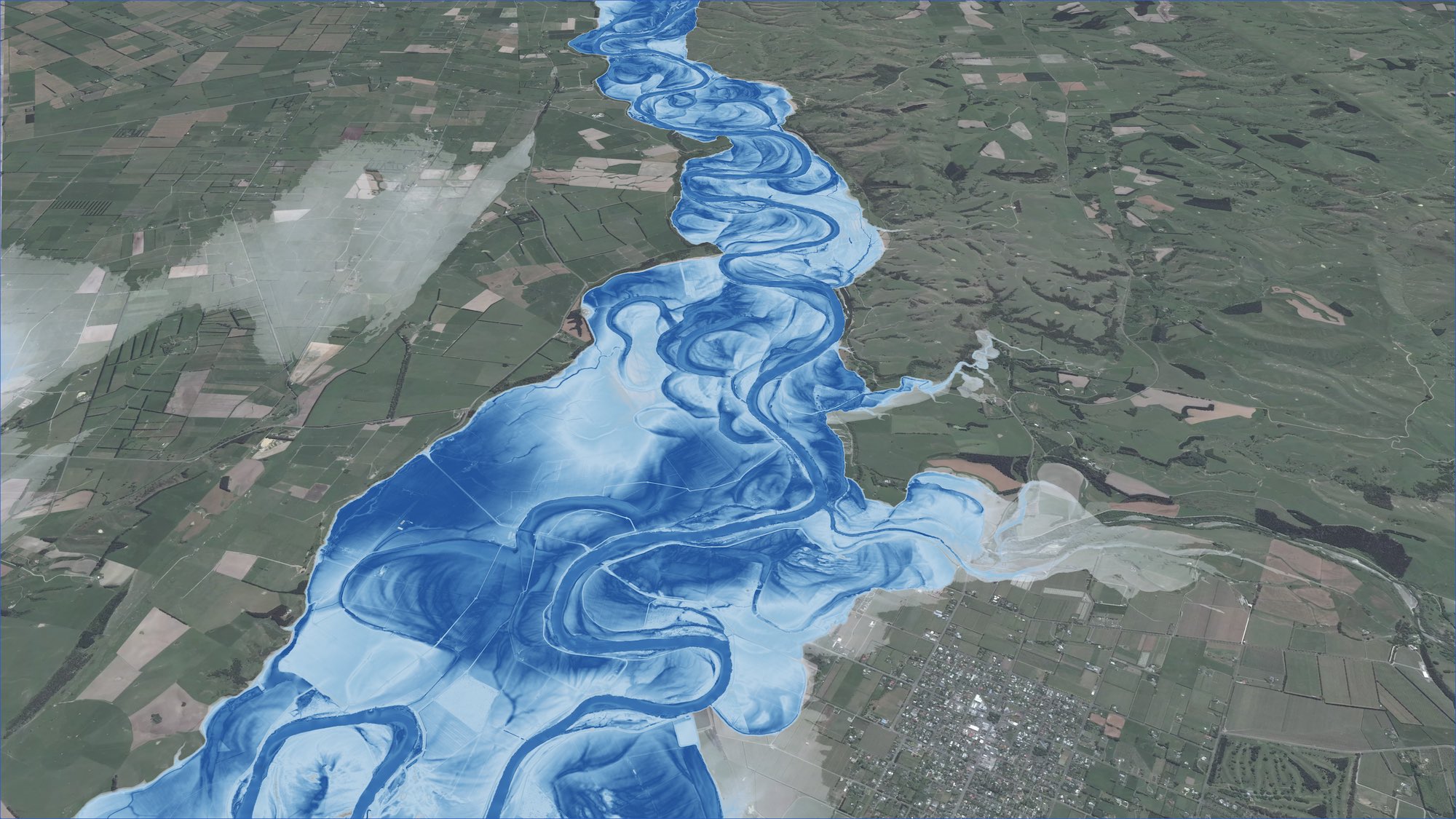

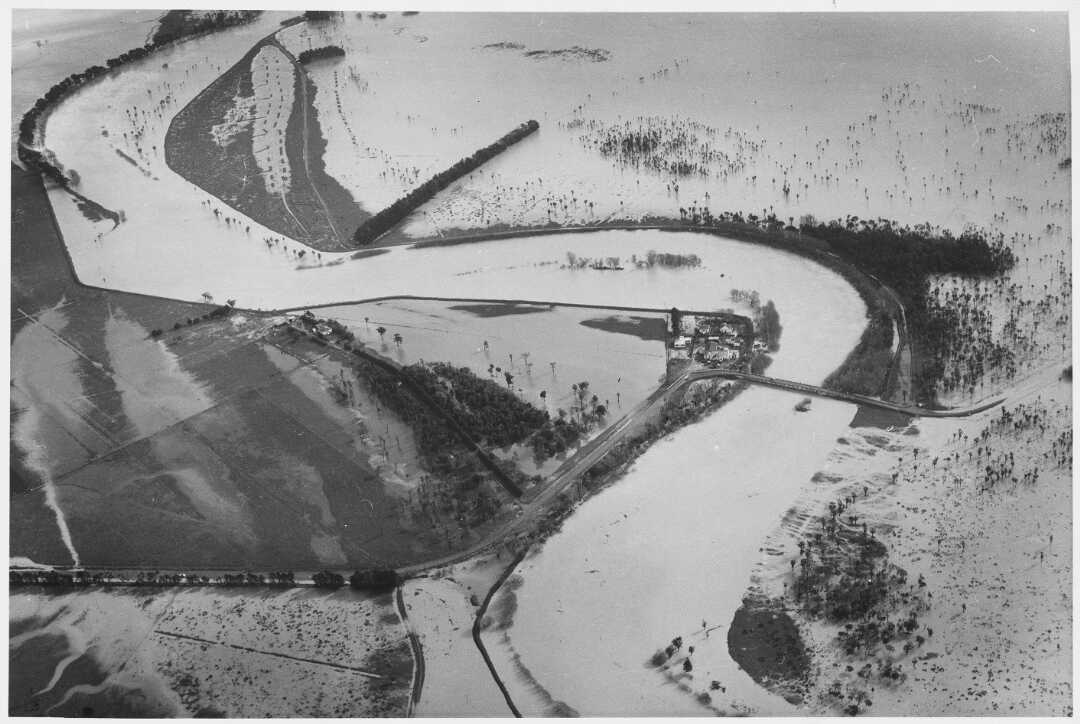

The Ruamāhanga River flows from headwaters in the Tararua Ranges, through the Wairarapa, before emptying into Palliser Bay. Looking at the river on Google Maps, you will see how it snakes down the floodplain through a crisp patchwork of fields, vineyards and townships. What is harder to perceive is that the river has taken many forms over time. The current channel is simply its most recent path across the landscape.

Rivers on floodplains do not stay in one place. They erode existing banks, build up new ones and abandon some channels altogether. Even as vegetation grows and humans claim the soils for agriculture, subtle traces of a river’s past forms remain, imprinted on the shape of the land. You just need to know how to find these patterns.

Compare the two images below. In the standard aerial photograph, only the active river channel is evident. The town Martinborough can be seen at the bottom of the frame.

The Light Detection And Ranging (LiDAR) imaging also offers clues as to which places are most susceptible to flooding and how to design hazard response plans.

These “ghost channels” are reminders that rivers follow their own logic and are not beholden to human expectations. Rivers are wild things. We lose sight of this at our peril.

Living in a flood zone

Assessing risk for an entire country is a tricky business. The best available overview of New Zealand flood hazard areas is the 2019 New Zealand Fluvial and Pluvial Flood Exposure report. Produced by NIWA as part of the Deep South National Science Challenge, it summarises what populations and built infrastructure are currently at risk to river and surface flooding.

The scientists pieced together local government hazard plans to create New Zealand’s first national flood map. They further combined this composite flood hazard map with Census population data, building footprints, transport networks, electricity infrastructure, water pipes and land use. The findings are concerning.

Future climate change will cause sea levels to rise and could increase heavy rainfall events, potentially increasing flood inundation hazard. When these are coupled with urban development in or near active floodplains, they would expose New Zealand to more frequent damage and disruption from flood hazard events, leading to higher economic losses.

The analysis estimated that 675,000 people are currently at risk of river or surface flooding. The population counts were based on the 2013 Census and would be higher if repeated with the newly available 2018 statistics.

The following chart shows how this number breaks down by regional council.

How many people live in flood hazard areas?

Despite having less than half the population of Auckland, Canterbury had the most people (189,000), buildings (116,700) and infrastructure at risk. The majority of these people and built assets are located in Christchurch City. The next highest levels of exposure were in the populous regions of Auckland (118,200), Waikato (89,000) and Wellington (77,700).

Across the whole of New Zealand, it was estimated that there were 411,000 buildings, 19,000km of road, 1,500km of railway, 20 airports, 3,400km of electrical transmission lines and 21,000km of water pipes in flood hazard zones.

Remember, these estimates are about the present day. They describe the number of people and buildings that are at risk of flooding due to their proximity to rivers or floodplains.

It is also important to recognise that these numbers describe potential exposure. This does not imply that everyone living in a hazard zone will experience severe flooding during their lifetime. However, as the planet gets warmer, severe storms and flood events will strike more often. With each passing year the odds grow a little worse for people living in a flood zone.

Sea-level rise and coastal flooding

River and surface flooding from heavy rainfall form just part of the picture. New Zealand has the ninth longest coastline in the world, with hundreds of settlements dotted along its length. These places were established under an assumption that sea level is stable. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

New Zealand’s sea level has already risen 20cm since the early 20th century.

New Zealand mean sea-level rise since 1901

Average sea level is forecast to rise even quicker over the coming decades. This will make coastal land more susceptible to flooding from storm surges and king tides. In a 2019 report, Coastal Flooding Exposure Under Future Sea-level Rise for New Zealand, NIWA scientists investigated who and what is at risk to coastal flooding today and how this will change as sea level rises. The report’s modelling used extreme floods with a “one-in-100-year” return period as the basis for the analysis.

Scroll down to see some of the key points.

Source: RiskScape data directly supplied, NIWA (2019)

Scientific measures like temperature anomalies or sea-level rise values seem unremarkable, even benign, when encountered in news articles. What difference could a degree or two make?

Because these numbers are so small, we tend to trivialise the differences between them – one, two, four, five. Human experience and memory offer no good analogy for how we should think of those thresholds, but, as with world wars or recurrences of cancer, you don’t want to see even one.

Small numbers mask uncomfortable scenarios. For every 10cm that the seas rise, thousands more people and billions of dollars’ worth of buildings and infrastructure become exposed to potential flooding.

The 2015 Parliamentary Commission for the Environment report, Preparing New Zealand for rising seas, cautioned that, while there is time to prepare for the future impacts of sea-level rise, “in some places and situations, action is urgent”. These actions include restricting new subdivisions in low-lying coastal areas, mitigating the effects of erosion on beaches where homes are already threatened, and working with communities before decisions are made.

Addressing these problems needs care and strategy. The water is not going anywhere – and when tested, it usually wins.