Habitats

What will happen to Aotearoa’s plants and animals?

Data essay by Chris McDowall

Aotearoa’s ecosystems are already under strain from habitat loss and introduced pest species. A warmer climate, more extreme weather and rising sea levels will intensify these stresses. These data interactives explore which plants and animals are under threat and how New Zealand will become a more hospitable climate for invasive species.

Eighty million years ago the landmass that would become Aotearoa started breaking away from Gondwanaland. Over the next 20 million years, Zealandia separated from Australia and Antarctica. The Tasman Sea opened up and this landmass became a chain of islands. Unique flora and fauna evolved during the millions of years of subsequent isolation.

The stakes are high

The term “native species” refers to plants and animals that naturally live in a particular area. An “endemic species” is a native species that only lives in that place. The ruru/morepork is native to Aotearoa, but it is also widespread in Tasmania. The kākāpō is endemic because it is native to New Zealand and nowhere else.

New Zealand has a very high number of endemic species. All of Aotearoa’s reptiles, native amphibians, bats and 90% of freshwater fish are all only found here. The same goes for 80% of vascular plants and 70% of all native land and freshwater birds. These organisms are found nowhere else in the world, and many are under threat.

Conservation status of native species

Aotearoa’s native species have endured environmental challenges over millennia. They overcame these through some combination of adaptation and migration. What is different this time is that change is happening extremely fast. Some native species will be unable to respond quickly enough.

Making things worse, over hundreds of years, humans have systematically drained wetlands, felled forests and converted huge swathes of plains and hill country to pasture. Outside of conversation parks, much of the remaining land with substantial indigenous biodiversity is fragmented into pockets. How do we expect species to find more suitable habitats when they are ringed in by farmland, urban settlements and commercial forestry?

Where are the frogs?

Charts provide an overview of how many species are threatened and at risk, but they are silent on the nature of these challenges. Understanding what we risk losing requires us to go beyond the numbers.

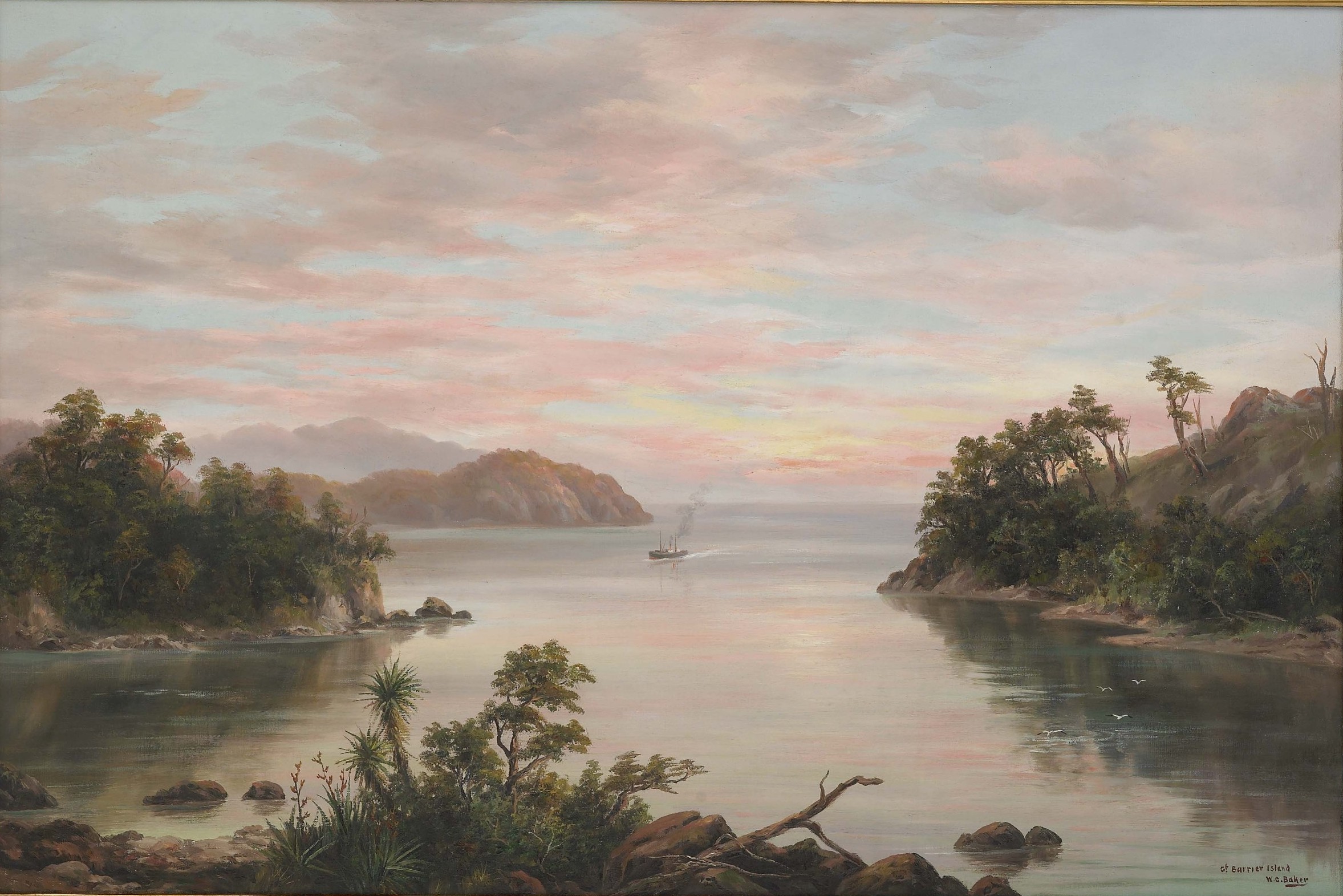

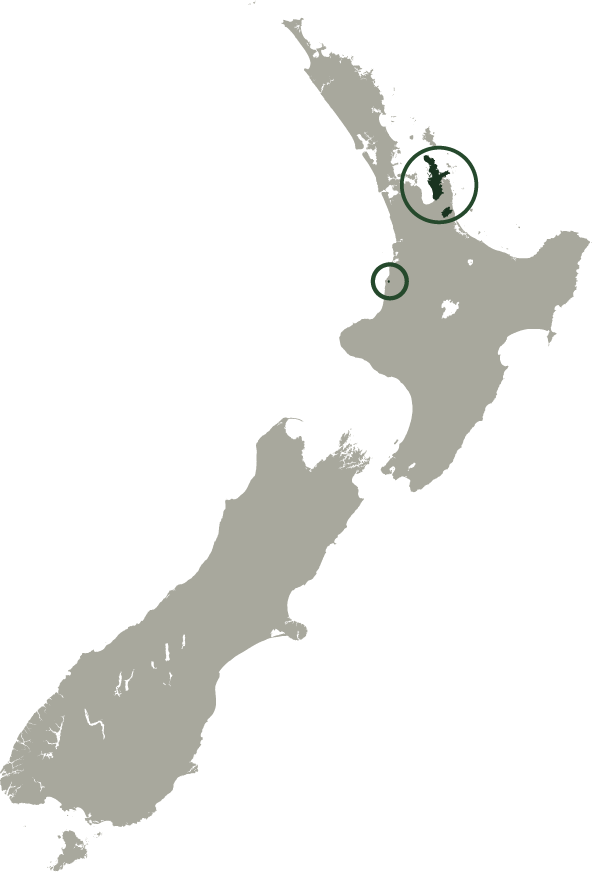

Aotearoa once had seven endemic species of frog. The three largest species became extinct due to habitat destruction and the introduction of non-native mammals. Another, the northern Great Barrier Island swimming frog, is so rare that there have only ever been two recorded sightings and taxonomists suspect it may be extinct. The three remaining species have severely reduced distributions. These ancient lifeforms have survived for 70 million years, but today they are at profound risk.

The greatly diminished range of species shown in these maps presents a bleak picture. A changing climate compounds existing threats of habitat destruction and predators. Our native frogs are not very mobile, but their world is changing. As alpine ecosystems shrink, sea levels rise and wetlands experience increased floods and droughts, what will happen to endemic species like the tuatara, brown kiwi, takahē and Archey’s frog?

New Zealand has tough decisions ahead around how to prioritise conservation resources. What species do we make a concerted effort to assist? What do we leave to fend for itself? Who makes these calls? How much money and effort do we invest?

More difficult questions for uncertain times.

Tropics moving south

This series focuses on Aotearoa and climate change, but everything discussed happens in a wider context. It is called “global warming” for a reason.

Aotearoa is surrounded by millions of kilometres of ocean, and these waters are getting warmer. The tropics are physically expanding with the warmer temperatures. The distribution and population of marine species are changing as new organisms arrive from the north, while some existing populations move south to cooler waters.

Scroll down for more.

Source: Sea surface temperature projection data supplied directly, NIWA (2020)

Source: Bactrocera Tryoni (Queensland fruit fly) Climex Ecoclimatic Index data directly supplied, SCION (2015)

The Queensland fruit fly infests over 200 species of fruit and vegetables. Crops at risk include avocado, citrus, feijoa, grape, tomatoes, peppers, persimmon, pipfruit and summerfruit. The fly will seriously damage our horticultural industry if it ever establishes here.

Shifts in species habitat suitability will happen on land and in the seas. Sensitive native species will need to move south or to higher altitudes to find suitable environmental conditions. Meanwhile, warmer temperatures and fewer frosts will make the country more hospitable to a host of exotic pests, weeds and diseases. The nation’s ambition to become predator free by 2050 literally faces an uphill battle as hills and mountains warm up and become more accommodating. No matter how effective our control methods, we are fighting against shifting temperature and hydrological cycle baselines.

Climate changes everything.