Tikanga and te reo Māori teacher Nicole Hawkins questions why non-Māori artists use Māori narratives and bodies in their work.

I can recall as an early teen sitting in a crowded movie theatre watching an advertisement for Victoria University play on the big screen. At that time the series of ads posed a variety of philosophical questions: ‘What will we do when antibiotics stop working?’, ‘How are thousands of years of classical art still influencing us today?’. These were all followed by the tagline, ‘It makes you think’. Whoever did the marketing for those ads did a damn good job, because one of the questions posed on that day was ‘Can you copyright culture?’ and I’ve been thinking about that very question for the past 17 years.

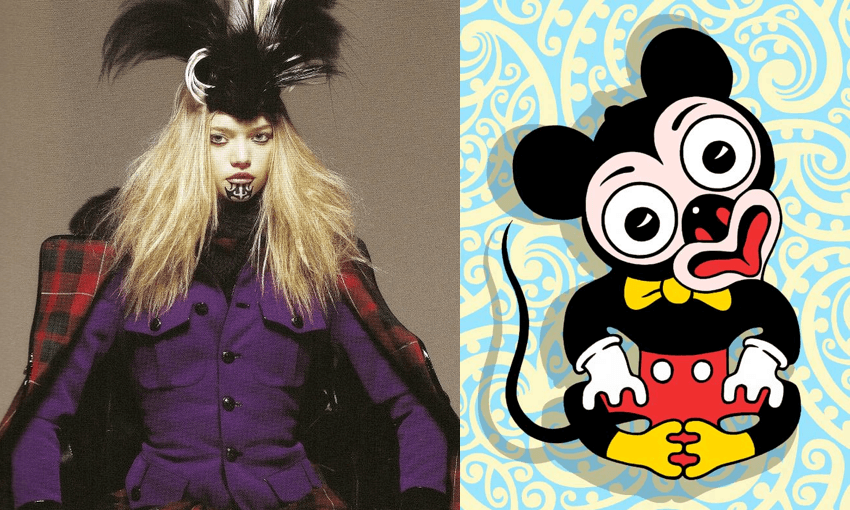

I followed the whakaaro all the way back to Victoria University for my undergrad and soon found that the answer is, no you can’t copyright culture – and I think it’s a damn shame. There were plenty of examples for my impressionable young mind to learn about, particularly showcasing the appropriation of Māori culture. Learning about Jean-Paul Gaultier’s use of moko kauae on models to promote a collection in 2007 had me wondering why a creative genius, with an estimated net worth of $100 million, needed to exploit a Māori art form to help build his already impressive fashion empire.

Māori and non-Māori alike were perplexed when Moana Maniapoto faced pricey legal action from an offshore company who had trademarked the word ‘Moana’ when she released her self-titled album in Europe. I would really have liked to talk about Te Rauparaha’s haka ‘Ka Mate’ and what I see as its exploitation by Adidas, the All Blacks and drunk ex-pats on London pub-crawls as a prime example of misappropriation. Although it hasn’t been copyright protected, it has since been made law that you must attribute ‘Ka Mate’ to Te Rauparaha.

In recent years we have got better at discussing, calling out and critiquing cultural appropriation, at least in our own backyard. Just this February, the Auckland music festival Splore made headlines for taking a zero tolerance stance on inappropriate cultural costumes, such as First Nations North American headdress and Hindu bindi. We have a full spectrum of things to say when celebrities such as Robbie Williams and Ben Harper arrive here wanting Māori designed tattoos (they are kirituhi, not tā moko). It seems we are getting better at deciding what’s OK, and what’s not; from defining what is acceptable to portray on our beer bottles, and what is deemed appropriate to wear to a dress up party, or what we let our kids wear to a school athletics day.

When does Māori culture amalgamate into New Zealand culture and become fair game for non-Māori artists to employ as a part of their own narrative? The widespread use of Māori imagery and themes is problematic, especially when Pākehā are selling that narrative off at the click of a mouse and New Zealanders are buying it, in print, on mobile phone covers, beach towels and cushion covers.

The rise of social media has given our local creatives a platform to share their work, gain popularity and of course, make sales. I recently started following the work of New Zealand Pākehā artist Erika Pearce. Her work is undoubtedly beautiful and features Māori women, iconography and mythology. While Pearce is passionate about Māori culture, te reo and other indigenous cultures, she says she doesn’t work with local iwi to ensure she is fairly and accurately portraying Māori stories (with the apparent exception of a mural made in collaboration with Ngāti Kahungunu whānau). She has built her business on the backbone of someone else’s whakapapa, and profits from this as an artist, a woman and a New Zealander. As a potential customer and supporter, this is an issue for me, and it’s not because I don’t think her talents should be celebrated, and I don’t write this to discourage creatives from engaging with te ao Māori.

Pearce clearly is talented and has a passion for aspects of te ao Māori, but does she and the many artists just like her have the cultural competency to uphold the mana of Māori stories without undoing the generations of work that many Māori have invested in correcting and re-telling them? Although her work is visually appealing to many, especially Māori, the telling of Māori histories is best done by Māori. A self-proclaimed story-teller, Pearce insists that her intention is to empower women by sharing their stories with the world. As a Māori woman I feel disempowered by a Pākehā assuming the role of storyteller (and seller), when my tīpuna wrote the book of which I am a living, breathing character.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t want the image of my tīpuna shipped off-shore, to be printed on a beach towel for someone to sit all over. Māori stories should be told by Māori, or at the very least, in collaboration with Māori, who are paid fairly for their time and expertise. Otherwise aren’t Pākehā artists with good intentions just making bank by perpetuating the cycle of post-colonial privilege, the very attitude they say they seek to change?

The concept of image exploitation is not a concept we find difficult to understand when a large, established business uses a trademarked concept from a local New Zealand artist. This is exactly what happened in 2015 when Northland artist Lester Hall found himself facing a legal battle with Australian surf label Billabong after they used his trademarked term ‘Aotearoaland’ in one of their t-shirt designs. Hall had his knickers in a twist over the breach, and quite rightly so. But it does raise a few eyebrows considering we can see the injustice of a small business owner being ripped off by a global brand, yet we don’t hold Hall and his art to account for exploiting Māori histories and imagery in the same way.

Hall is another celebrated artist who uses images of Māori women as the main subject of his work. One controversial piece Remember Them features the depiction of a tipuna Māori, Ahumai Te Paerata, who courageously fought at the battle of Ōrākau.

Without knowing anything about Hall, I knew from the moment I laid eyes on Remember Them that the artist was likely not Māori. Would Māori portray their tīpuna as a glossy haired, perky-breasted, low slung blanket-wearing dusky maiden? Don’t even get me started on the nipples. To make matters worse, on his website Hall claims that it’s his prerogative to label himself ‘tangata whenua’, and that “Māori academics” “marginalise” him as a white male in this country. He implies that tikanga Māori is inherently sexist and outdated in comparison to his own core values. When we are debating his right to expression, let’s remember that. Could Hall’s work ever enhance the mana of our tīpuna?

The sexualisation of indigenous women has been an issue plaguing the Pacific since Cook and his homeboys set sail and before Gauguin’s oils had even started to dry. Wāhine from all over the Pacific have been writing back and speaking up against the notion that, outside of raising children, cooking and keeping a whare looking spic and span, that the only other space indigenous women can inhibit is that of an object of desire, often for the enjoyment of white men. This is not to say that our wāhine aren’t beautiful, and shouldn’t be admired as such, but we are doing all of our women – our tīpuna, our mothers and our children – a disservice to reduce their image and identity to a fetishised, and often Westernised, ideal of beauty. If we are calling this Māori art, then shouldn’t wāhine be able to see themselves reflected back in the images, in full form, raw, complex and unashamedly Māori?

Pearce has become well-known for her work featuring beautiful Māori women, and is set to open her exhibition, The Wahine Project. Likening her objectives to Lindauer and Goldie, Pearce wants to leave a legacy in the telling of what she describes as “our cultural identities”, whilst lifting and empowering women. I discussed the project with a group of Māori women based on the images available on Pearce’s social media, which offer sexualised images of wāhine Māori. One of us concluded that, “It appears that people prefer the dreamy, half-naked, idealised version of wāhine Māori to the powerful and complex reality.” When considering why this might be, one woman responded, “That’s because one hangs in their living room and the other hangs in their conscience.”

Being a Māori woman presents challenges in almost all aspects of life, in a variety of measures. Is it not our duty to protect the integrity of the mana wāhine identity, by demanding that this overt-sexualisation and idealisation stop? Especially when the cultural identity being portrayed is not a collective “our”, unless the artist and storyteller is Māori. No, not all wāhine Māori have gorgeous flowing hair, hourglass figures or wear their korowai in a cleavage baring manner. I’m also certain that when my tīpuna were defending the sacking of their pā, that they didn’t stop for a second to reposition their hei tiki suggestively between their pert breasts, or consider whether their eyebrows were #onfleek. We owe it to our young women to ask for the full spectrum of Māori beauty, and to not settle for the telling and re-telling of dusty, dusky maiden fables.

Yes, many will say that artistic expression allows these artists the freedom and control to create their work as they see fit. Art without whakapapa, without history, is still art, but it remains very influential. As Māori and New Zealanders we should tread carefully to ensure that our artistic contributions (and acquisitions) portray Māori narratives which honour them authentically. If it’s not your story to tell, aren’t you just occupying the space of someone who could tell it better? Māori are renowned for their storytelling abilities. Our reo and culture has survived against the odds, in the face of colonisation, because of our ability to pass our kōrero from an intergenerational ocean of memory, to tongue, to ear. Māori don’t need Pākehā artists to tell their stories for them. What we do need are allies who can love and acknowledge our rich histories and identities without making them their own, and calling it #MaoriArt.

Update 22 Mar: original feature image removed at request of whānau featured in mural.