The inventor of the Vortex Fluid Device tells Charles Anderson how the machine that famously converted a boiled egg back into its original state could have huge implications.

Professor Raston is a panelist at this week’s AMN8 conference in Queenstown.

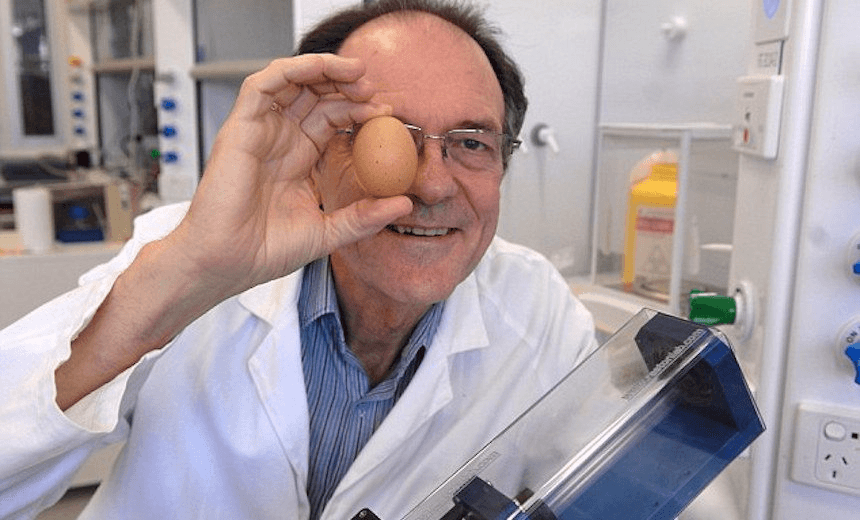

The boiled egg has both blessed and haunted Professor Colin Raston.

For the past two years whenever he has traveled from his home in Adelaide to myriad conferences around the world there is always one question people ask:

“You’re not one of the guys that unboiled the egg are ya?”

Raston is. He is one of those guys that unboiled an egg. Even at AMN8 he cannot get through his presentation without mentioning it at least once.

But it was never about the egg. What Raston was trying to do was to find a economic and efficient way of unfolding proteins – a sticky issue for the pharmaceutical industry.

On a flight back from Los Angeles to Sydney he mapped out an idea where this could be achieved by creating a machine that revolved rapidly on an angle. At more than 2000rpm, liquids would go through the same process as they would if they were being manipulated in large processing facilities. But Raston’s idea could do the same thing in the size of a coffee cup.

“From the outset we were trying to put scalability into chemistry,” he says.

The angle of the machine, dubbed a Vortex Fluid Device, put the liquid material under immense stress. If you put the same material in a conventional round bottomed jar, different molecules might meet but it would be random occurrence, known as diffusion. In the VFD they were forced to slam into each other.

“You put chaos into the mixture,” Raston says.

When scientists prepare proteins to study elements, such as antibodies to detect cancer, some of the product is lost. The proteins can be “over expressed” turning them into a sticky useless solution.

Scientists then have to back track to put the proteins back into their original state. But to do this is messy, expensive and time consuming.

The VFD changes that. And one of the easiest ways to see how it operates is using a conventional hard boiled egg. When you boil an egg the proteins in it go white because they “misfold” or become unstable. The unstable proteins stick together to form a gel. But by putting that gel into the VFD it effectively stretches out those proteins and puts them back into their original state.

When the research went out two years ago it only took Scientific American an afternoon to call Raston up at his home. Then the unboiling egg meme was born. Raston won the infamous Ig Nobel prize for his work.

But the VFD has more going for it that just an award. Along with benefits for the medical community, it can also be used to create bio fuel and help pharmacists synthesise drugs. The list is growing.

“Whenever I do a talk there are questions after and we seem to be able to come up with another potential application,” Raston says.

Which is part of the benefit of conferences like AMN8, he says. There will inevitably be someone among the 500 plus delegates who has an idea for collaboration.

“I always tell my students conferences are 50 per cent about the science and 50 per cent about networking.

“You can be best scientist in the world but the world can choose to ignore you if you don’t network.”

This is part of a series of articles for the Spinoff about and from AMN8, The Eighth International Conference on Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, in Queenstown from February 12-16 2017. For details on public events in Christchurch, Wanaka, Queenstown and Nelson, click here. This content series is sponsored by the conference’s hosts, The MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology, a national institute devoted to scientific research.