Inheritance plays as part of The Basement Theatre’s Matariki season this week. Sam Brooks talks to one of its creators about what the show wants to say.

Jess Holly Bates has quite a bit of experience making shows that start conversations.

Her show Real White Fake Dirt critiqued Pākehā privilege in a way that was both scorchingly intelligent and riotously funny. Her show The Offensive Nipple Show, created with Sarah Tuck, advocated body positivity and rampant nudity in a series of hilarious, highly physical sketches.

Her latest show, created with Forest Kapo, doesn’t look to start a conversation – it looks to continue one.

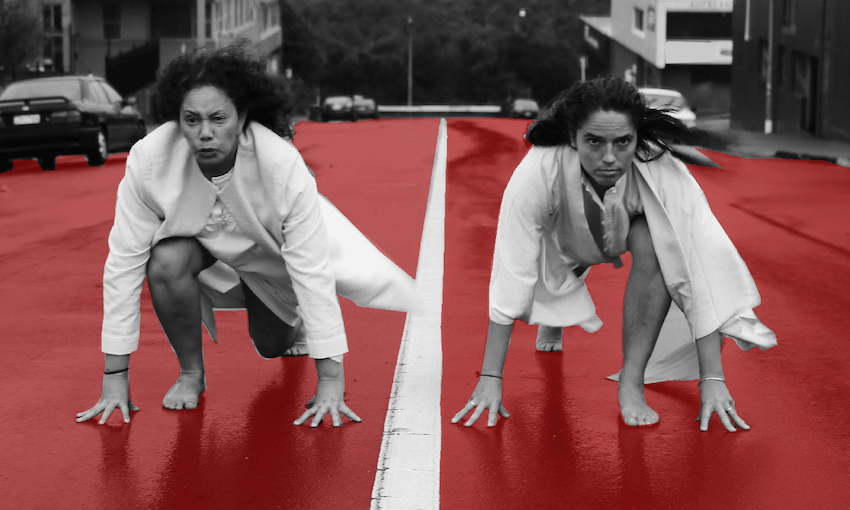

Inheritance bills itself as “a quivering sitcom of the colonial present”. To deconstruct that, it’s a show about the inequality crisis currently plaguing New Zealand, using a variety of theatrical forms. The idea is to encapsulate both Bates’ and Kapo’s stories of class difference – Bates is Pākehā, Kapo is Māori – and then encourage an audience to interrogate their own privilege.

According to Bates, the show came from the pair wanting to address parts of their friendship, particularly the difference in their backgrounds. “When you have great differences in a friendship, like you find your own language to communicate, but actually when you look at the icebergs that you’re standing on, it can be quite confronting. We’re using our embodied experiences as a gateway to talking about a much bigger inequality gap that’s happening.”

A key reference point is the ‘Mother of All Budgets’. The 1991 budget was the first one delivered by then-minister of finance Ruth Richardson, and it was arguably so unpopular with the public that it not only cost National the next election, but ushered in electoral reform on the whole. “I’m a child of the Mother of All Budgets, and so are a lot of us – we all carry these intrinsic beliefs about the way society is organised that aren’t actually natural. They’re cultural, they’re political.”

“In a way, it’s a love song to Ruth Richardson – what would it be if you’re lying in bed next to the person with a completely different experience from you, and you have to feel and build a relationship? What does that even look like?

On the surface, it sounds like one of those shows that’ll be confronting you with how wrong you are, and how wrong your existence is. Those shows exist, and there’s a limit to how much use they can be in a world where people are engaged with so many conversations at the same time, conversations around just about every societal issue that you can name. On one side, an artist could have an audience who aren’t ready to engage with what you’re saying, and on the other, an artist could have an audience who are so advanced beyond what the work is engaging with that it can seem remedial. People hate being pandered to as much as they hate being preached to.

Inheritance is neither pandering nor preaching.

When Bates talks about Inheritance, she talks about it as a ‘post-book show’. By that she means that this isn’t a play that is trying to prove that anything exists. It’s not a head’s up about racism, or sexism, or classism. These things absolutely exist. “The conversation starts from the point that we’ve all read the book, we all know that inequality exists. It’s not interesting to me to try and pose the argument, or convince this audience. I’m interested in something beyond that, so to me it’s a conversation about healing, and it’s the feeling of healing. And I mean that’s the form as well.”

There’s a genuine care and keenness in making sure that the audience is held, and not just talked at. That gentleness doesn’t just seem key to this work, but the work that Bates is setting out to make in the future as well. “How can we hold that knowledge, and how do we cope with what we know? It requires a real tenderness, because knowing where we stand in the world, knowing our privilege, is a hard thing to hold.”

Bates is refreshingly frank about her Pākehā heritage, and what that means in the context of a Matariki season as a co-creator. “It’s interesting being Pākehā and being inside the Matariki framework. You have to be very delicate with that, but at the same time I think it’s important that we can fold together because I am a person of the Treaty, like that’s the reason why I’m here, I’m Tangata Tiriti.

“So that’s my reason for why I stand in this Matariki framework because I think it’s really important to go ‘Okay, what would it be not to disavow the history?’ What would it be to stand here and try and actively feel and listen?’ I feel firm in the kaupapa that we are building something beautiful and necessary, and that we want to open up a conversation – as opposed to in the past, where I’ve really yanked conversations open.”

For Bates, it’s about staying in the conversation and not disengaging. It’s about listening (‘not just with your ears, but with your whole body’) and being open to what’s being discussed. “If we can decolonise the conversation enough, we can go ‘it’s not about winning or getting it right’.”

“There’s no such thing as fucking it up, it’s about staying in the room. Staying in the room is the whole thing, you know?”

Inheritance runs July 9 – 13 at The Basement Theatre, Auckland. You can buy tickets right here.