To celebrate Taranaki heritage month, Airana Ngarewa remembers local leader Riwha Tītokowaru.

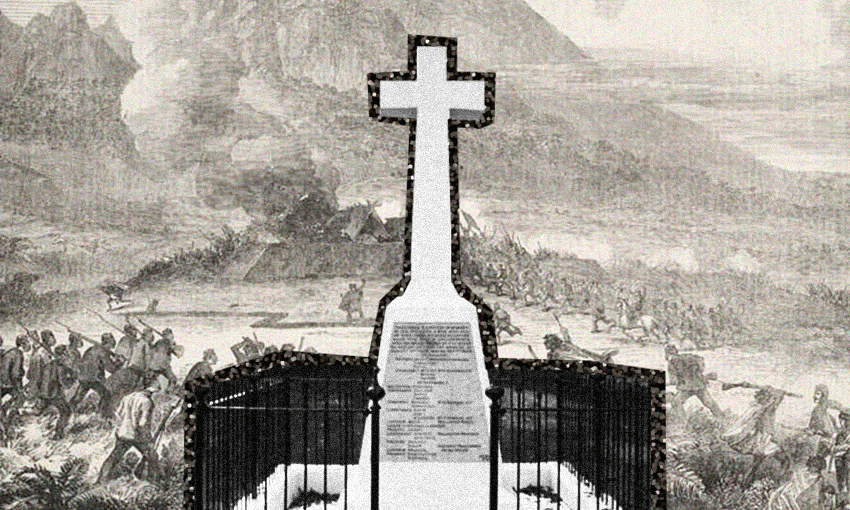

Until very recently, there was little about Te Ngutu o te Manu that told of its tremendous history. There was a single large white concrete cross that remembered the names and ranks of the pākehā who lost their lives attacking it. Included among them is the infamous Gustavus Ferdinand von Tempsky, an adventurer, artist and soldier known to mana whenua as Manurau, one hundred birds. There is also an almost illegible blue plaque that remembers the 100th centennial of Thomas McDonnell’s attack in 1868 and at last, a larger sign which summarizes the legacy of this site in less than 100 words.

A historical reserve in the heart of South Taranaki and the site of two former pā, Te Ngutu o te Manu was once home to the greatest military strategist of his time, Riwha Tītokowaru. It was from there he preached peace and when peace was no longer an option, defeated a colonial force that outnumbered him six to one. This year marks the long-awaited return of this wāhi tapu to its rightful owners, Ngāti Manuhiakai – Tītokowaru’s own hapu – and the unveiling of a pouwhenua, carved and posted as a reminder of all that had once resided there.

Growing up in the shadow of the musket wars, like many in his era, Tītokowaru was a child of the faith, serving under the Methodist John Skevington, the first sitting reverend of South Taranaki. Having seen the aftermath of war, Tītokowaru would become a fierce advocate for peace, resorting only to warfare when his peace options were exhausted.

Though there remains some debate about the details of his younger life, this happened at least two times in his life: The first time occurred when he fought alongside ngā iwi o Taranaki against the crown in the early 1860s, losing an eye and many of his uri, when the crown reneged on its promise not to buy land without the consent of all those who owned it. The second and final time occurred when he led the fighting against the colonial forces in another bout of warfare in Taranaki, driving the fighting front 50 kilometres south from Te Ngutu o te Manu, where this renewed bout of fighting began, ultimately delivering the crown one of the most devastating losses it had ever faced.

It is for this second bout of war that Tītokowaru is most remembered. There is perhaps nothing that encapsulates his fighting spirit better than his words found penned on a note left on a cleft stick on a road between Māwhitiwhiti and Maihī: E kore ahau e mate, kāore ahau e mate, ka mate ano te mate, ka ora ano ahau. I shall not die, I shall not die, even when death itself is dead, I will be alive.

Remarkable as Tītokowaru’s fighting feats were, by his own descendants he is remembered as a seeker of peace, truth and justice. Much of this mahi he completed at his home pā, Te Ngutu o te Manu. Before his time, it was known as a sanctuary, a place of rongoa and learning. This pā was razed in 1866 by Trevor Chute as part of his scorched earth policy alongside 27 other kainga and countless amounts of crops in the Taranaki rohe.

Alongside his followers, Tītokowaru rebuilt the pā early the following year. It would become comparable in many ways to Te Whiti and Tohu’s Parihaka. There were 58 houses, a large marae and a wharenui from within which he was known to perform ancient rites and what was observed by Kimble Bent, a deserter from the colonial forces, as magical acts. Given the name Wharekura, the wharenui was built in only six days in accordance with the time it took God to create earth and was said to be around 25 meters long, beautifully carved and lined with raranga. At one end it was also said to possess a raised platform from which Tītokowaru would address his people, delivering messages of peace.

Five large hui took place at this pā over 15 months, manuhiri coming from every corner of Taranaki. Envoys too would travel far afield, preaching peace in Tītokowaru’s name. Perhaps Tītokowaru’s most impressive feat of peace was a 140-man march that led from Camp Waihī, a colonel military base, and stretched all the way to Pipiriki. On these journeys, he preached compromise, toasting Queen Victoria and accepting the loss of Ngā Ruahine land where he believed it could not be avoided. It was also on these journeys that he preached the words: Whakarongo! Whakarongo mai e te iwi! Tenei te tau tamahine, tenei te tau o te rameti! Make it heard! Make this message heard! This is the year of the daughter, this is the year of the lamb!

The mana of these acts is even more remarkable when they are appreciated within the context of enduring colonial aggression, the loss of his eye to a colonial gun and Chute’s scorched earth policy which reduced not only important taonga to ash but the very kai mana whenua survived on. So well regarded was Tītokowaru’s mahi that James Booth, the Pātea resident magistrate, wrote “he has shown the most untiring energy in his efforts to bring other tribes to make peace. He has visited all the hapūs between Taranaki and Wanganui, and has now succeeded in bringing them in.”

Now, though the fortifications have been destroyed, the wharenui Wharekura has been lost to time and the earthworks have been flattened, the newly-unveiled pouwhenua stands as a symbol of Tītokowaru’s campaign for peace, his driving back the crown when this campaign failed and the return of Te Ngutu o te Manu to its original guardians.

Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.