Whether you make an effort or not, either way it sends a message.

The word “tryhard” tends to carry derogatory connotations. In this country, at least, there’s a very specific prevailing nervousness around being identified as one. For most of my life, I’ve subscribed to this seemingly relaxed attitude, clutching to the idea that making an obvious effort to excel is cringeworthy to the highest degree. This distaste was probably at its peak throughout high school, best reflected in my lack of competitiveness in any sport I played, low-key ball dress choices and persistent uniform infringements.

There are times when it’s entirely valid to resist exerting too much effort, but at other times there’s nothing wrong with embracing our inner tryhard. One such moment is when it comes to our pronunciation of te reo Māori.

We’re in an astonishing space in the revitalisation of te reo Māori. Mainstream conceptions of the language have been transformed through the efforts of activists and advocates. But in some corners there remains a persistent resistance to pronouncing kupu correctly. It’s most apparent in a number of obstinate educators, CEOs, politicians and broadcasters (naming no names) that insistently mispronounce kupu Māori, but it’s pervasive too in everyday conversations that you might have with your neighbour or cousins.

The late leader and education pioneer Tā Toby Curtis (Ngāti Pikiao, Ngāti Rongomai, Te Arawa) said in an interview with Stuff at the beginning of this year that while every Māori can speak English and is expected to pronounce English words correctly, that wasn’t reciprocated when it came to te reo Māori. “I’m looking forward to the day when all Pākehā, children and adults, can say every Māori word correctly,” he said.

This week marks 50 years since the Māori Language Petition was delivered to parliament by Hana Te Hemara (Te Atiawa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāi Tahu). Up until the late 1960s, te reo Māori was discouraged by official Crown policy and tamariki in schools faced corporal punishment for speaking it. The petition, provoked by growing fears that te reo Māori was dying out as an everyday language, asked that it be taught in schools. Those activists and the 33,000 signatures sparked the renaissance of te reo Māori.

Enormous progress has been made in the half-decade since. In 1987 the Māori Language Act, which recognises te reo Māori as an official language of Aotearoa, was passed into legislation. Today, we have television channels and radio stations dedicated to the language. Kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa and te reo Māori night classes are flourishing. It’s become commonplace in everyday life to see bilingual street signs, supermarket adverts, ATMs, or more recently, chocolate wrappers.

Still, I regularly find myself in conversations with people who would probably consider themselves theoretically supportive of te reo Māori revitalisation, sometimes my own friends and family, where Taupō is pronounced as if it rhymes with elbow, or Waikato as if it rhymes with eyeshadow. A hard, anglophone r repetitively conquers the softly rolled r that should be in my last name. Macrons go unnoticed and the word kūmara somehow loses a whole syllable.

What ruffles me about these instances is less the mangled mispronunciation itself, and more the frightening indifference to trying.

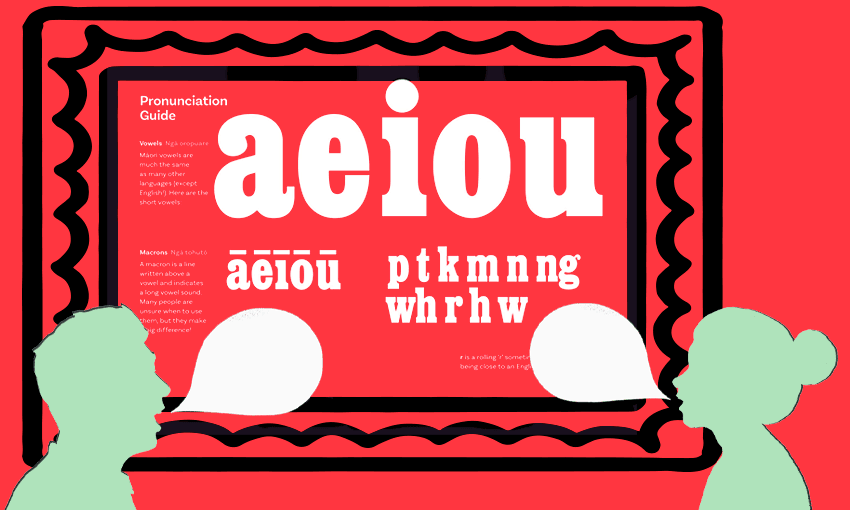

Importantly, there is nothing fundamentally wrong or shameful about fumbling kupu. For many who have grown up speaking English, and by no fault of our own, those rolled r’s, elongated vowels and non-English diphthongs sit uncomfortably inside our mouths. It’s not helped by the exclusion of te reo Māori in our education system and public life that has dominated most of our history since colonisation. Attempting to get words right can feel awkward, clunky and, at times, yes, like you’re being a tryhard.

Within these moments, I get the sense that mispronunciation of te reo Māori has been so normalised that it’s almost viewed as apolitical to do so – that to aim for accurate pronunciation would be to make some sort of political statement. The thing is, making no effort makes a statement too.

In the 1990 book Ngā Tohu Pūmahara, Māori leader and academic Tā Tipene O’Regan (Ngāi Tahu) pointed out the power and significance of place names in te ao Māori. He described Māori place names as ngā tohu pūmahara, meaning “the survey pegs of the past”. For a society that once depended on oral tradition, Māori place names convey far more than just geographical points.

“The most important role of place names in a society in which traditions and history were transmitted orally was to serve as triggers for memory,” he wrote. “They reminded those who spoke or heard them of events or episodes important in the history of the tribe. They were the means by which the tribe’s traditions and knowledge of its tūpuna were handed on.”

Similarly, the names of people are expressions of identity and connectivity. This isn’t unique to te ao Māori – for most people our names are the foundations of who we are. Knowing this, it’s not difficult to see how working toward correct pronunciation isn’t just respectful, but helps to maintain the enduring whakapapa captured within those words.

Making an effort with pronunciation, and respecting the importance of kupu doesn’t mean getting things correct, instead it’s about being open to the ongoing journey of learning.

Thankfully too, there’s an abundance of resources to lead us in the right pronunciation direction. Te Aka Māori dictionary website allows you to search for definitions and pronunciations of almost any kupu Māori. In July, Te Hiku Media launched an app called Rongo which was designed to help people to improve their pronunciation of te reo Māori and build their confidence speaking the language.

Engaging with Māori music, podcasts, television, film, TikTok, theatre and performance is an organic way to get used to hearing correct pronunciation. Sometimes it’s as simple as being open to being corrected when you haven’t said a word quite right, and making note for next time.

There is also an array of dialectical differences across the country, both between iwi and within. That means that what might be correct within the predominant Waikato-Ngāpuhi mita which has become standardised, might be incorrect in other parts of the country. Those distinctions only underscore how vital it is to be open to the learning process.

Like all indigenous languages, te reo Māori grew out of the lands, rivers, lakes, seas and skies of Aotearoa. Unlike English, there is nowhere else in the world where te reo Māori can flourish or be reclaimed. For that alone, there’s an immense value in maintaining the phonetic integrity of the kupu that make up the language. The more we speak te reo Māori, the better. And the solution to mispronunciation is as simple as a shift in attitude.

So go ahead – be a tryhard.

Follow our te ao Māori podcast Nē? on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.