As the fight to revitalise te reo Māori continues, kōhanga reo are grappling with severe teacher shortages, outdated facilities, and a lack of trust in their national leadership.

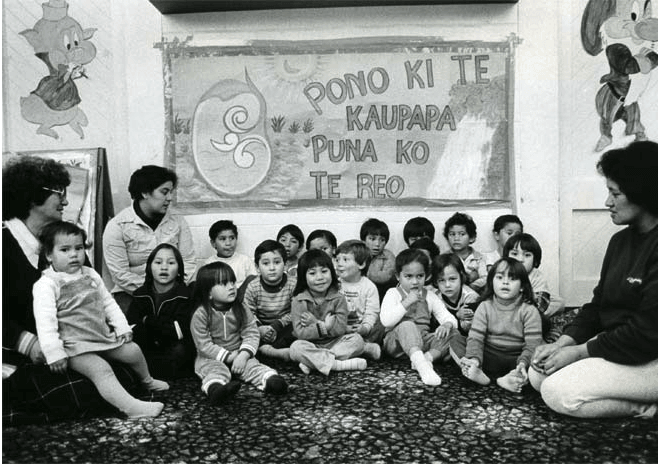

Te Reo Māori is integral to understanding the Māori worldview. It provides a window into te ao Māori that is nearly impossible to get from only speaking English. The first and only language spoken in Aotearoa until the arrival of the British, te reo Māori suffered greatly with the advent of colonisation and policies of assimilation. This led to the language becoming threatened with extinction. There has been an ongoing struggle to revitalise te reo Māori ever since – a battle that begins with kōhanga reo.

“It’s not that we don’t have the space, it’s just that we don’t have the kaiako,” says Cherie Tai-Rakena, kaiwhakarite at Te Kōhanga Reo o Mataatua ki Māngere.

While the number of people speaking te reo Māori continues to grow, the percentage of speakers relative to the country’s population remains stagnant. Meanwhile, there are children around Aotearoa missing out on the opportunity to attend kōhanga reo due to a severe lack of kaiako. Some whānau are on waitlists almost two years long, with dozens vying for a very limited number of spaces. According to Tai-Rakena, there are a few factors that have contributed to the shortage, beginning with changes to the funding structure in 2008.

Although there has never been a specific government mandate requiring all kōhanga reo kaiako to hold teaching certificates, funding structures introduced by the Ministry of Education have created indirect pressure to employ certificated teachers. Since 2008, kōhanga reo funding rates have been tied to the proportion of certificated teachers, incentivising their employment but also creating staffing challenges. This shift impacted the availability of teachers deeply rooted in the kaupapa and fluent in te reo Māori. Nannies and kaumātua raised as native speakers of te reo were effectively pushed out of kōhanga reo in their droves.

A 2021 report revealed mixed trends in kōhanga reo staffing and training between 2015 and 2020. Qualified kaiako numbers rose from 430 to 496, and kaiāwhina increased from 158 to 216, while uncertified staff dropped sharply from 2,422 to 1,943. Māori-medium early learning services grew slightly by just over 3%, from 484 in 2014 to 500 in 2020. However, enrolments in kaiako training with the Kōhanga Reo National Trust plummeted 32%, from 420 in 2014 to 260 in 2020. Initial Māori-medium (kōhanaga reo and puna reo) teacher training courses saw an even steeper drop, falling 25% from 20 enrolments in 2016 to just 15 in 2020. Then Covid-19 happened.

There is no official data available on the number of kōhanga reo teachers that left the profession during the pandemic but Tai-Rakena says the vaccine mandate introduced for teaching staff in 2021 had a severe impact on the number of kaiako available to teach in kōhanga. “Some chose not to, and as a result, they couldn’t work. Now, years on, those who left the kaupapa have moved into more lucrative jobs.”

With many kōhanga being forced to close their doors or greatly reduce their roll capacity, pay parity became a key priority of the Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, the central body supporting kōhanga reo across Aotearoa. “Attracting kaimahi comes down to pay – without higher wages, it’s hard to grow. We’re striving to move kaimahi to a living wage, but it depends on roll size,” Tai-Rakena says.

In March 2023, the Trust introduced optional pay parity, mostly in response to the Wai 2336 Waitangi Tribunal recommendations, ensuring kōhanga reo kaimahi are paid comparably to those in other full immersion settings. Over 140 whānau opted into the system, which involves the Crown providing additional funding to cover salary costs based on the kaimahi qualifications, experience, and mokopuna numbers.

Administered through a centralised payroll by Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, it supports equitable pay while allowing whānau to manage employment contracts, pay scales, and additional salary contributions. Updated pay bands for roles like kaiāwhina and kaiako range from $49,200 to $115,086 in 2024, reflecting experience and responsibilities.

Tai-Rakena took a significant pay cut to help lead the kōhanga where her children went. She believes kōhanga reo would do well to model some processes off their Pākehā counterparts. “I like how Pākehā kindergartens pool their funding. For example, my daughter-in-law works at a kindy in Tokoroa and all their money goes to a central head office. She does the same job as me but earns over $100,000 a year because larger kindies support smaller ones under the same umbrella.”

When it comes to support for te reo Māori, the coalition government has been criticised for a raft of policies that have been perceived as being anti-reo Māori and undoing decades of hard fought wins from reo Māori advocates. Although she did not respond to requests for comments for this article, minister for education Erica Stanford has previously been quick to highlight the government’s annual $3m budget allocation for kōhanga reo facilities.

Tai-Rakena is quick to point out that the $3m doesn’t work out to be much when split across all 400 kōhanga reo currently operating in Aotearoa. If distributed evenly, each kōhanga reo would receive approximately $7,500 annually towards the maintenance and upgrade of its facilities. For kōhanga such as Te Kōhanga Reo o Mataatua ki Māngere, the third oldest operational kōhanga in the country, the figure is a drop in the bucket towards addressing the plethora of maintenance issues affecting its dated facilities – something that Tai-Rakena says is also contributing to their issues attracting quality staff. “Some are drawn to flash facilities rather than focusing on the quality of teaching. They care more about how modern the building is than what their child would actually learn”

Although Te Kōhanga Reo o Mataatua ki Māngere has just successfully managed to fill two kaiako roles, it took years for them to find suitable candidates. In the meantime, five of its six classrooms sit empty, with all current students learning in one classroom.

When questioned about the path forward and the role Te Kōhanga National Trust has to play in all of this, Tai-Rakena doesn’t seem to have much faith in the Trust’s ability to effectively advocate for kōhanga such as hers. In 2019, the Trust was found to be severely dysfunctional, with a lack of proper policies and processes leading to the misspending of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“There’s a lot of mistrust in the Trust. Many kōhanga don’t feel supported financially or emotionally. For us, we’ve learned not to rely on anyone and just do what we need to do…The ministry calculates our funding, but it goes to the Trust before it comes to us.”

A key issue raised by Tai-Rakena was the Trust’s lack of availability and communications. In response to our requests for comment on the Trust’s strategy around addressing the teacher shortage issues, the Trust responded by saying it could not provide a response as “it is difficult to see where we are in this strategy”.

Te Kōhanga Reo o Mataatua ki Māngere reflects a broader crisis facing kōhanga reo nationwide. The fight to preserve te reo Māori cannot succeed without systemic change – adequate pay, safe environments, and trust in leadership. As classrooms sit empty, the question remains; what will be done to secure the survival of te reo Māori for future generations, or will this vital cornerstone of Māori identity continue to struggle?

This is Public Interest Journalism Funded by NZ On Air.