On the marae, debates over pronouns are raging, all while we strive to revive a language that doesn’t even have them in the first place.

A version of this article was first published by Critic Te Ārohi.

If you’ve ever done a course on Duolingo, you’ll probably have noticed that the French think shovels are feminine and cheese is masculine. But te reo Māori doesn’t really place emphasis on masculine and feminine nouns, and instead garners much of its contextual meaning from whakapapa (genealogy). English isn’t big on gendered nouns either, but English and other Western languages insist on personal pronouns. While this might seem dismissable, the implications are quite insidious: if your entire worldview is narrated by the gendering of objects, gender becomes a central factor of life.

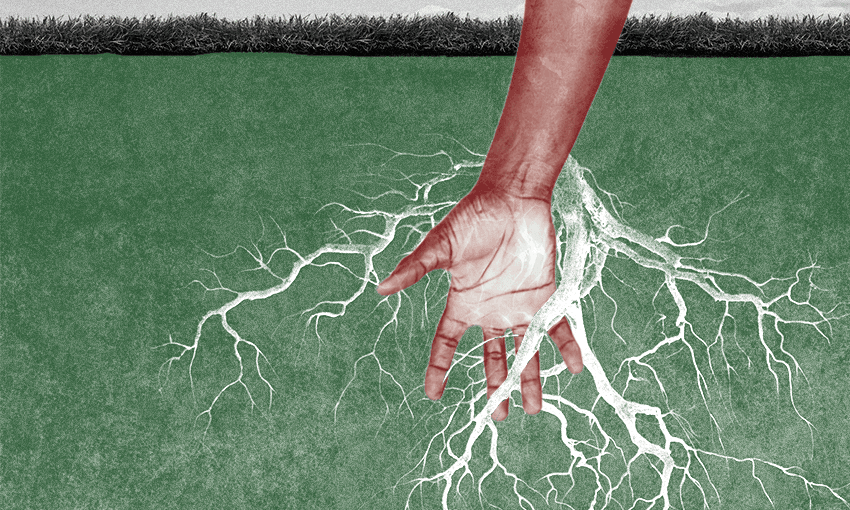

As tāngata whenua, our relationship with the land stands as a testament to the intricate bonds that exist between people and the environment. We trace whakapapa to the natural world, bury our afterbirth in the whenua, and eventually return to the earth from which we came. But it is the marae, the heartbeat of hāpori Māori, that unites tāngata whenua across the motu. Honestly, it’s undeniable – it’s in our roots. It is our roots. And it’s here on the marae where debates over these pronouns are raging, all while we strive to revive a language that doesn’t even have them in the first place.

To some, the marae is but a labyrinth of protocol steeped in age-old traditions. Some Māori find themselves disillusioned by marae formalities, which doesn’t make them want to visit. From gendered bathrooms, to organised sleeping arrangements and fixed gendered roles, many marae across the motu are embedded with gendered normalities. Between the piercing call of the karanga, to the hākari where all hands blend to fix a feast for the multitudes, varying degrees of procedure characterise every marae and its people. This is known as “kawa”, a concept that is similar to tikanga. The kawa of every marae and hapū is almost guaranteed to change based on location: for example, in parts of the Far North, women are not permitted near carving workstations, and iwi such as Tainui and Te Arawa follow the tau utuutu (alternating speeches) method during whaikōrero. But are there kawa that directly impact the experiences and role, or lack thereof, for takatāpui? Waitapu (Ngāpuhi, Rongowhakaata), a fourth-year student in Auckland, spoke of her own experiences.

Kupu like “takatāpui” have origins in places like Wairarapa. But here, there and everywhere, with or without the title, these people have always existed. Waitapu took aim at a particular institution. “Up at home, the influence of the Church clearly takes precedence over tikanga, and I just didn’t fuck with it,” she said. “I constantly felt like a burden; like that relative with a thousand dietary requirements, when really I just didn’t wanna sleep next to all the tāne… don’t get me wrong, other marae I visited during kura were quite accepting. It be your own that don’t.”

At its core, takatāpui embraces diversity while rejecting the notion that gender and sexuality are binary categories. And historically, Māori society embraced these identities. So where did it all start to shift? I’ll let you take a wild guess.

“The relationship between takatāpui and tāngata whenua is fractured, and for people like me, it’s impacted my desire to go home,” said Waitapu, who agreed that judgement has, over time, expanded to other Māori who don’t fit a certain description: from urban Māori, to white-passing Māori and can’t-speak-the-reo Māori, the taumaha is real. “We make fools of our whanaunga for shit they had no say in – no Māori just decides to be white-passing or willingly abstains from te reo at birth. But here we are, making it a running joke.”

What we consider “the norm”, however, wasn’t always normal, considering the gendered hierarchy was just as foreign as tāngata pōra. It just wasn’t a thing back then. You can see this in te reo Māori, as both personal pronouns (ia) and possessive personal pronouns (tana/tona) which are gender-neutral. But the sudden arrival of Christianity and Victorian values forever changed Māori society, shattering all ideas of gender diversity and placing men firmly at the top. Today, through cultural revival and a surge of international pride, some of these traditions are reemerging.

But isn’t that the whole point? Atawhai (Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Raukawa), a graduate student in Kirikiriroa who identifies as iakē (genderqueer) believes external influences have had a detrimental impact on Māori for the benefit of colonisation. “We are fracturing our relationships to align with a standard that didn’t once try to understand our own,” they said. “Instead of kissing the white man’s arse, why can’t we love our own people? We preach ‘manaakitanga’ to foreigners, and then don’t manaaki our takatāpui – make them feel like accessories.”

And moving towards or, in many cases, back to a (genuinely) takatāpui inclusive space on the marae is a vital step towards recognising their contributions to the development of te ao Māori. Waitapu agreed that the first step in the right direction goes beyond pronouns – a no brainer, really. “Getting my pronouns right is like foreplay… you kinda should just do it. The reo is already inclusive. But the active work we need to do is rethink traditional gender roles and expectations,” they said. “We have so few tāne that are fit to speak on the paepae, which is what drove me away from home – not being allowed to speak on the pae as a transwoman. While I don’t have a burning desire to, I was raised to do so.” Atawhai added, “It’s clear to me now, that our people have religious trauma and need to have a wānanga with themselves about it. Until then, I don’t have to put up with it.”

“Considering the extensively recorded importance of our female and takatāpui ancestors, and the role they held throughout history, only to become a false narrative… my tūpuna would be spewing in their graves.”

Who are we to deny our roots, muddied hands and all?