Kīngi Tūheitia’s visit to Parihaka on Saturday was the first of his reign, but it followed a long tradition of goodwill between the Kīngitanga and Taranaki that grew out of a shared commitment to peace, writes Airana Ngarewa.

For the first time in his reign, the Māori king, Tūheitia Potatau Te Wherowhero VII, visited Parihaka on Saturday November 18. This follows a longstanding tradition of monthly hui held at Parihaka on the 18th of every month that regularly draws in Māori and non-Māori from across the country. This day remembers the first shot being fired by the Crown on Te Kohia Pā on March 17, 1860, beginning what would be a 21-year campaign of resistance in Taranaki and concluding with the invasion of the pacifist settlement on November 5, 1881.

After the pōwhiri was conducted, a wānanga took place between ngā iwi o Taranaki, taiohi representing every kura kaupapa in the region, and the Kīngitanga. This continued a legacy older than the kura, Parihaka and the Kīngitanga.

Before his coronation in 1857, the first Māori king, Pōtatau Te Wherowhero, was a renowned warrior known only as Te Wherowhero. For more than 20 years, he led an ope of Tainui warriors in what is known as the musket wars, a period of fighting between Māori that was catalysed by the introduction of the musket. The wars ended for Tainui and Taranaki with a siege from the future king on a set of twin Pā, Waimate and Orangituapeka, on the southern Taranaki coast just outside of Te Hāwera.

Over several days, the siege continued, but despite the warriors of Taranaki being vastly outnumbered and having far fewer guns – some accounts recording that they began the battle with only one – the fighting ended with a permanent truce being called between the rival ope. Peace has endured between these confederations of tribes since that day in 1834 and is remembered by Te Wherowhero’s words to Wiremu Te Matakatea, the leader of the warriors from Taranaki.

“This is my final peacemaking; I have ended – ended for ever; and shall return at once and not come back. Your lands remain with you on account of your prowess. Were I to fight again after this my arm would be broken under the shining sun.”

When Pōtatau Te Wherowhero passed away, he was succeeded by his son Tūkāroto, known also as Matutaera. In respect of his father’s connection to Taranaki and the growing influence of the Pai Mārire movement, a Māori faith combining the tenants of Christianity with traditional Māori beliefs, the second Māori king travelled to Taranaki in 1864 where he would be bestowed the name Tāwhiao by Te Ua Haumene, prophet and founder of the Pai Mārire movement. This ceremony took place at the head of the Kapuni awa, the stream that divides that twin pā where his father made peace with the Taranaki tribes.

In response to both confederations of tribes enduring mass confiscation of land by the crown, Tūkāroto Matutaera Pōtatau Te Wherowhero Tāwhiao II prophesied that these lands would one day return to their rightful owners. “You, Taranaki, have one handle of the kit, and I, Waikato, have the other. A child will come some day and gather together its contents.”

It is the history of peacemaking, shared experience of the unjust mass confiscation of land and commitment to peace that bonded Taranaki and the Kīngitanga. On account of the latter, the prophet Te Whiti o Rongomai III, who founded Parihaka alongside Tohu Kākahi, said “He maungārongo ki te whenua. He whakaaro pai ki ngā tāngata katoa.” Peace on earth and good will to mankind. For his commitment to peace, Kīngi Tāwhiao is remembered as Kīngi o te maungārongo. King of peace. And so, the legacies of Taranaki and the Kīngitanga have long been interwoven.

Over the weekend, leaders of both confederations braved the rain, stood from their respective paepae and shared stories over the day, which oscillated between this shared history, acknowledgement of what each has contributed to the world and then what more needs to be done to ensure the prosperity of all people here in Aotearoa and those suffering injustice overseas. One theme prevailed in all that was shared: unity. To this end, Dr Ruakere Hond, an esteemed leader of Parihaka, stressed that “we need to bring our kōrero together and share our insights.”

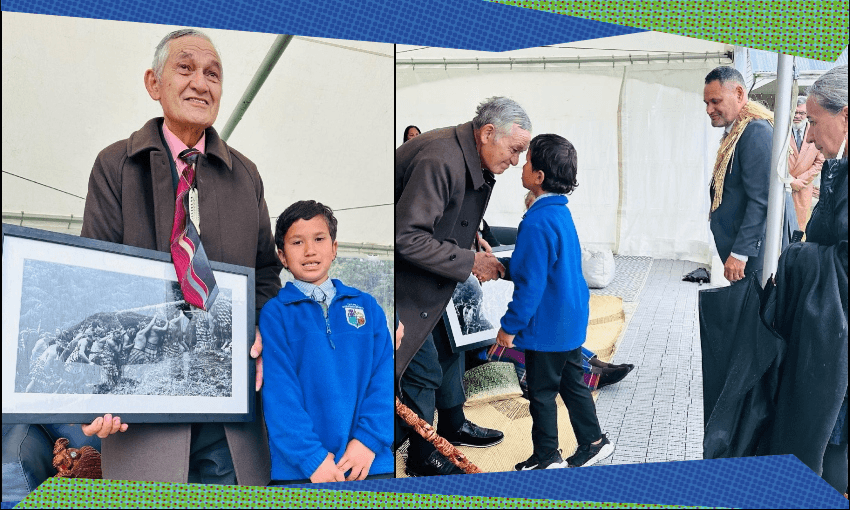

Taiohi from all three kura kaupapa of the region travelled to Parihaka, lining up to perform the haka pōwhiri for the king and standing in support of each of the speakers from Taranaki with a variety of waiata that link the two groups. Before the king departed, he was presented with an original photograph of his grandfather, Kīngi Korokī Te Rata Mahuta Tāwhiao Pōtatau Te Wherowhero V, being carried by a group of men atop Taupiri Maunga, the sacred burial ground of Tainui.

For many of the taiohi, this weekend marked the first time they would have met the Māori king and for all of them, the first time they were able to welcome him under the shadow of their maunga. And so as Kīngi Tāwhiao inherited his father’s deep connections to Taranaki, this new generation of taiohi inherited their connection to the Kīngitanga.

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.