Dance down memory lane with us to a time when the Māori showbands ruled supreme.

After World War II, Māori concert parties became a huge attraction in Aotearoa, like the kapa haka groups we know and love today. Action songs and haka were still a novelty for Pākehā New Zealanders that hadn’t been to Rotorua and knew nothing about Māori culture and concert parties would tour all over Aotearoa and regularly sell out venues to massive crowds.

One of the earliest groups to combine contemporary music with kapa haka was Te Pou o Mangatawhiri, who were born from a group of children orphaned in the Waikato by the influenza epidemic of 1918 and gathered up to be cared for by the surviving adults and Te Puea Herangi aka Princess Te Puea, daughter of the Māori king Tawhiao Te Wherowhero. She wanted to build a better home for them so the group were taught kapa haka and a number of instruments, and travelled throughout the North Island performing to raise money. When the carved meeting house Te Puea built for her people opened in 1929, 6000 people came to the opening.

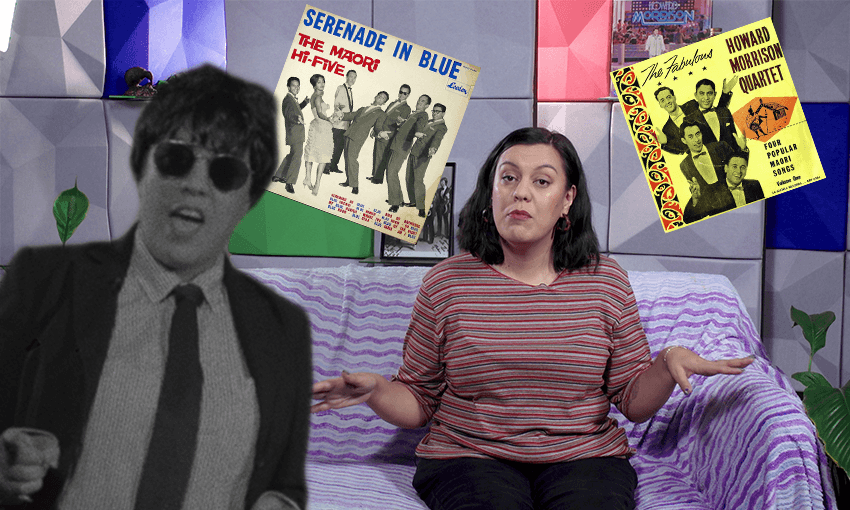

Te Pou o Mangatawhiri inspired an interest in Māori music everywhere they went. In the mid-1950s Te Awapuni Māori concert party from Hastings followed suit, featuring a talented young performer named Howard Morrison. A Pākehā businessman named Benny Levin recognised a business opportunity and took over management of Te Awapuni, adding Howard Morrison and the Clive Trio to his roster, and later the Howard Morrison Quartet, along with Gerry Merito, Wi Wharekura and Noel Kingi.

With their combination of soulful waiata, swing standards and humour, the quartet had hits with ‘Hoki Mai/Po Karekare Ana’, ‘The Battle of Waikato’, their parody of ‘The Battle of New Orleans’ and ‘My Old Man’s an All Black’, a parody of the Lonnie Donegan song ‘My Old Man’s a Dustman’. The beginnings of the Māori showband as popular entertainment, and as a real money maker, was born.

It was about this time rock n roll and the Hawaiian sound were taking off. It was a complicated time too, with a lot of emphasis by the government on Māori assimilation into Pākehā society. Māori were leaving their tribal rohe and heading to the cities to find work, and naturally congregating in places where they could be with each other. And as ever, that involved music. Bands started popping up everywhere. They played dancehalls, soundshells, marae, surf life saving clubs, anywhere with a floor and a roof basically.

One of the first and most famous of the big show bands was the Māori Hi-Five, the template for what was to come if you will. Whanganui teenagers Ike Metekingi and Kawana Pohe met Rob Hemi, a guitarist from Wairarapa, at a hui in Ruātoki. They later hired multi-instrumentalist and singer Solomon Pohatu from Ruatōria, and recruited Rarotongan percussionist, Fred Tira, and drummer, Tuki Witika. They combined comedy, cabaret, kapa haka, and rock n roll with impeccable dress sense and soon began performing as the Hi-Five Mambo around Wellington.

The group were quickly pegged by another couple of enterprising Pākehā businessmen, Charles Mather and Jim Anderson, as ones to watch. The duo took over managing the group, who changed their name to the Māori Hi-Five. Mather and Andersen ran a tight ship, whipping the group into an entertainment machine. The sets had to be slick, fast paced, and full of variety, and above all they had to be seen to be enjoying themselves. Mather and Andersen were incredibly strict with the group and fined them for any indiscretion – being drunk, being late and even not smiling enough on stage.

They were so popular a flood of Māori showbands quickly followed after. After the success of the Hi-Five, Mather and Andersen founded the Hi-Five Company, developing more bands for the hungry audiences. Next came the Māori Hi-Quins, the Quin-Tikis, and the legendary Rim D Paul from Ohinemutu in Rotorua.

Meanwhile, copy cat acts were popping up everywhere and promoters would book them without auditioning or hearing them because the reputation of the Māori showbands was so strong.

Of course, Aotearoa wasn’t big enough to sustain all these working musicians. In 1960 the Hi-Five, along with singer Mere Nimmo (

Most of the bands went through a number of line-up changes and members moved around from group to group. At the peak of the Māori showband phenomenon, in the mid-1960s, you could find members of the Hi-Fives, Maori Troubadours, the Maori Hi-Liners, the Quin Tikis, the Maori Volcanics, Te Kiwis, the Premiers, the Maori Hakas and the Maori Minors in any Sydney or Gold Coast nightclub.

And from this amazing stable of groups came some of our biggest stars – Prince Tui Teka, Billy T James, Frankie Stevens, John Rowles.

Unfortunately, the international success of these bands didn’t necessarily get the respect it deserved at home. Many of the groups reported low tickets sales when they returned to New Zealand triumphant from successful tours of the UK. And so many of those great performers settled in Australia and the UK, and never returned home. In 2010, the Māori Hi-Five were honoured on the Las Vegas Walk of Stars. There was only one New Zealand news camera there.

After the cultural renaissance of the 1970s, and the realities of the effects of colonisation on Māori became more apparent to the New Zealand public, our music and our message became more political, and that is whole other wonderful era of music, as is our traditional music and our incredibly diverse contemporary artists.

But many of the wonderful musicians of the showband era are passing away and I don’t want us to forget these incredible performers.

Their legacy lives on!

Watch more: When the Haka Became Boogie