The return of Te Matatini this year was a triumphant success – but how might it evolve by the next iteration in 2025, and beyond?

This past week marks what has for many been their least productive workdays of the last four years. The ringaringa and waewae of so many institutions have transformed as their tupuna Māui transformed before them, becoming eyes instead – eyes glued to images of their whānaunga twirling poi, knee-dropping and putting on performances so profound even Ranginui couldn’t help but shed tears the whole week through. This was Te Matatini Herenga Waka Herenga Tangata 2023, the Olympics of kapa haka.

The whakataetae has come leaps and bounds from its beginning in Rotorua in 1972 when Waihīrere Māori Club (finalists again this year) claimed the top prize at what was then the New Zealand Polynesian Cultural Festival. The number of kapa haka has doubled, and the number of spectators and level of competition has increased too. Not to mention the quality of the broadcasting, including live translations of the finals in five different languages.

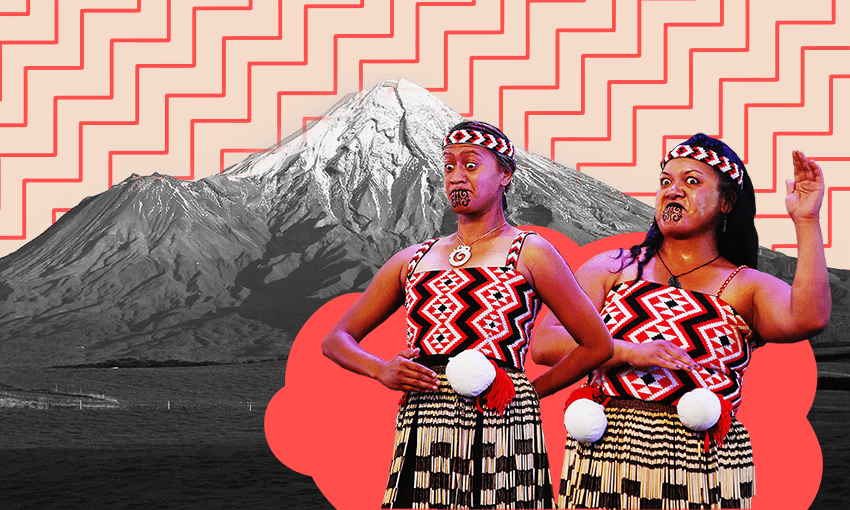

Te Matatini will next be held in Taranaki in 2025, moving from the most populous city in the motu to one of Aotearoa’s least populous regions. Already the wānanga have begun, iwi and waka coming together and reflecting on this year’s whakataetae and how we might build on that success, honouring the legacy of the event while at the same time adding our own flavour and propelling the event into the future. This is the whakataetae behind the whakataetae, each rohe competing to host an event more stellar than the last.

Reflecting on these wānanga, I am left to wonder how the whakataetae might transform even beyond the next event. Having recently celebrated Te Matatini’s 50th birthday, I am left to ponder how it might look in another 50 years’ time.

If the number of kapa haka doubles again, the structure of the whakataetae could change. The simplest response would be an extension of the length of the whakataetae and either the introduction of a semi-final or the number of teams selected to participate in the final. However, when such a pool of talent is available, there may be much more that Te Matatini could offer both kaihaka and their audience. There is the potential for more divisions to be introduced. Perhaps they could hold a more traditional section reminiscent of the kinds of haka our tūpuna would be familiar with and a contemporary section where kaitito are encouraged to push the boundaries and test the definition of haka. Such a change would certainly make the mahi of the judges easier.

As it stands now, judges must contrast and compare many different styles and forms. This means the results are inevitably questioned – who should and should not have made the finals, who should and should not have won each item and the whakataetae overall? If not separate divisions then it may make sense to introduce a series of official People’s Choice pou where viewers at home or the kaihaka themselves vote and award their own taonga.

With more kapa haka, perhaps the structure could shift more radically, introducing a haka season where every rōpū competes weekend to weekend like rugby and netball do, accruing points until a top 16 are selected and compete at an event similar to Te Matatini we know today. Such a change might even support a professional or semi-professional competitive haka industry where tutors, manukura tāne and manukura wahine (if not all members of a rōpū) are no longer volunteers but professionals whose expertise and whakaaro are recognised and rewarded.

This raises the question about the individual items themselves and how they might change across time. In an attempt to draw more rangatahi into the whakataetae, kapa haka could turn to more modern styles of waiata like rap or pop, where the rangi of Aotearoa’s hit waiata are adapted to te ao haka. Or with an even younger audience in mind, they could turn to oriori instead. Then there is the possibility of a reversal of roles where as in the stories of old tāne twirl their poi and wāhine haka. And then, again, there is the influence of our takatāpui whānau who will continue to shape te ao haka and make the stage their own.

Given so much of the bracket is grounded in taonga puoro, it is interesting to note that every kapa haka uses a guitar and in recent memory, only one has ever used the cowbell – whāia te Iti Kahurangi. It is hard to imagine that in 50 years the popularity of the acoustic guitar as the preferred instrument will have faded, but it is interesting to consider what might replace or accompany it as each kapa haka seeks to take their performance to the next level. The ukulele, the violin, the bagpipes. It is also interesting to consider how waiata ā-ringa and other items might change in response, matching the natural rangi of these taonga puoro.

Might it one day even make sense to extend Te Matatini beyond competitive kapa haka to other performative arts in te ao Māori? Could it one day host a manu kōrero for pakeke or a tautohetohe between iwi or rohe? Might it one day become the Olympics of all things Māori, broadcasting waka ama then kī-o-rahi then a whakataetae to see whose whānau has the best creamed pāua, boil up and rewena bread? So diverse and multi-faceted is te ao Māori the possibilities are endless.

Undoubtedly Te Matatini will grow larger and the pool of talent deeper and the audience more and more hungry for haka. In the afterglow of this year’s whakataetae, now is the time that we as a people must reflect, kōrero and ponder deeply our hopes, wishes and aspirations for the future of Te Matatini and competitive kapa haka. Nō reira this is the wero: Aotearoa, how would you like to see Te Matatini and competitive kapa haka transform over the next 50 years?

This is Public Interest Journalism funded through NZ On Air.