From the outside, and often the inside too, the local punk scene might not seem especially connected to te ao Māori. A local punk band is working to change that perception.

Imagine a bustling mosh pit at a punk gig in Aotearoa and you might very well picture a crowd that’s predominantly Pākehā, and one that’s predominantly male too. A messy, ragey sea of studded jackets and combat boots in which few would even attempt to find similitude with te ao Māori.

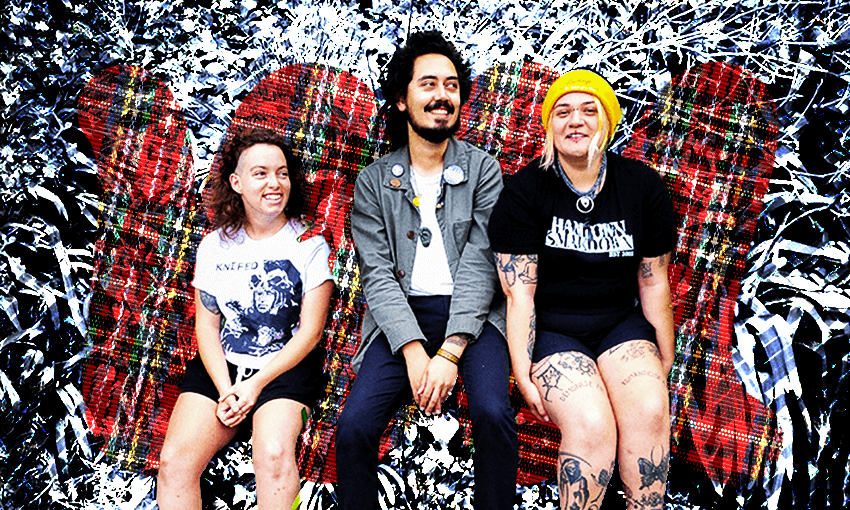

But for local punk band Half/Time, made up of members Wairehu Grant (Ngāti Maniapoto) on vocals and guitar, Cee Te Pania (Te Rarawa, Ngāti Kahu ki Whangaroa) on bass and Ciara Bernstein on drums, the ground where te ao Māori and the world of punk meets is their turangawaewae.

Half/Time grew out of Grant’s PhD research on the ideological crossovers of te ao Māori and punk culture, which he began in 2019 at the University of Waikato. Part of his research included interviewing eight people from across the country – including Te Pania – who saw themselves as belonging to te ao Māori and to the punk scene.

It was the academic process that prompted Grant to start making music during the 2020 lockdown, initially as a solo artist, incorporating the intersections between those two seemingly disparate worlds. Six tracks recorded and mixed at his home studio in Kirikiriroa came together to form the first self-titled EP which intertwines lyrics in te reo Māori and English to address decolonisation, structural racism and cultural resilience. Earlier this year, Te Pania and Bernstein joined the group.

At the beginning of May, the band will play the three day Focus Festival in Cymru Wales alongside more than 250 bands from all over the world. That’s a huge deal for the band, but the driving force behind the trip is language revitalisation. Grant and Te Pania, both at different stages of their journey to reclaim te reo Māori, will also speak at Cardiff University on a panel of musicians talking about performing music in their own languages, supported by the British Council and The University of Waikato.

“The band that really sparked my interest in all of this was a band called Fantails,” Grant says of the Wellington-based trio headed by Sarsha-Leigh Douglas (Ngāti Maru, Te Arawa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Kahungunu). “It was a kaupapa Māori led femme punk band and they were really, really cool.” Their music released over a decade ago marked the first time Grant had heard te reo Māori used in a punk context. The impression that left was transformative.

Douglas, a trailblazer in the intersecting worlds of Māori and punk, completed her 2014 thesis titled Outcasts and Orchestrators: Finding Indigeneity in Aotearoa Punk Culture. Within its pages she noted that, “though not acknowledged as a realm heavy with indigenous participation, punk culture has the potential to provide solidarity for the indigenous people it attracts.”

Like Douglas, for Half/Time there is something in punk that is deeply resonant with te ao Māori, even if this isn’t always apparent among the surface-level expectations of a politically detached culture from both within and outside the scene. “For some reason a lot of people think white boys in basketball T-shirts own punk or that it’s all just Blink 182, double kicks and skateboarding,” says Te Pania. “There’s so much more to it.”

Rather, punk’s resistance against the mainstream and status-quo, and its staunch affirmation of another kind of politics and sense of community, make it much closer to practices and values you’ll find woven into te ao Māori than one might initially think.

“These are always going to be heavily debated, but the pillars of punk that I see are an anti-authoritarian slant, a questioning of leadership and imposed rules and restrictions, and mutual aid,” says Grant. “A lot of that is echoed in te ao Māori, like when we think about tino rangatiratanga, whakawhanaungatanga and manaakitanga.”

Ōrākau, a song written by Grant and Te Pania and released by Half/Time last year, is a clear distillation of the political kinship between te ao Māori and punk. The song is dedicated to Grant’s tupuna who stood, despite being massively outnumbered, against colonial forces at the battle of Ōrākau in 1864 in the central Waikato. One of the warriors at the head of a group led to safety along the Puniu River was Grant’s ancestor Te Huia Raureti.

It’s a waiata with a decidedly determined tone as Grant chants above a crunchy bass, “ka whawhai tonu mātou ake, ake, ake,” we will fight on forever and ever and ever. “It’s a series of reminders to remember and cherish my tūpuna who came before me. In particular, the ones who chose to stand up to figures of power at a time of such massive upheaval,” reads the song description.

Politics runs in the veins of punk just as it does te ao Māori, explains Te Pania. “The whole point of the genre was about being countercultural.” But, “it’s convenient for people to forget that because then they don’t have to be political.”

Forgoing politics isn’t so easy when you’re Māori, though. And so often, having a foot in two seemingly disparate realms can make it feel like you belong to neither. In this case, too punk to be Māori; too Māori to be punk.

“When I first started playing in bands, I always treated those worlds as very separate,” says Grant. Because of a lack of visibly Māori crowds and performers, or ideas and language in punk spaces, he felt that his interests in punk didn’t align with what it meant to be Māori. With that came a feeling of detachment from te ao Māori. For Te Pania too, the composition of the scene has often felt isolating, “the punk world is not a solid place to be in when you’re not straight, not cis and not white.”

It has been through forging connections with other Māori in the scene, forming a band centred in te ao Māori and uncovering Māori punk bands gone before that has made it all feel less lonely for both. Within those connecting threads is a recognition that it links them to their tupuna too and that in some ways their interests exist within an ongoing tradition.

Te Pania looks to haka as an example of this. “Our tupuna have always been making heavy music, it’s just, they don’t use instruments, they use their bodies and there’s lots of stamps, but they knew how to project their voices.” When indigeneity is tainted by the falsehood that it’s relegated to the past, it’s a form of resistance to ensure that it continues to evolve into the future.

More than simply coexisting, there’s potential for these two worlds to strengthen each other. “When you realise how those two worlds combine, there is just something so special about seeing yourself in both,” says Grant.

Sometimes, while performing for Half/Time, Te Pania will look around in bewilderment. Not so much at the crowd jostling to get to the front of the mosh, but at the rest of the band on stage. The loneliness that comes from existing in between has given way to a new, more empowering experience of existing within both worlds.

“Synchronicity is a massive thing in te ao Māori,” says Te Pania. “There’s a reason you all move together with a kāranga, and you all eat together; it’s about the synchronicity, it’s the moving as one, kotahitanga, and when we’re doing this together on stage, it’s just this triangle of energy, I love it.”