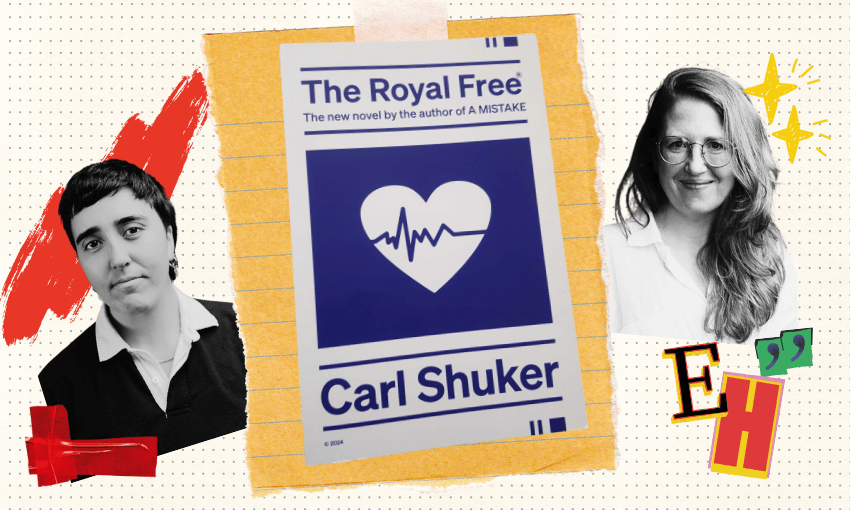

Spinoff editor Mad Chapman and books editor Claire Mabey debate Carl Shuker’s new novel about… an editor.

Claire: Hello Mad, you just finished The Royal Free – overall impressions?

Mad: Hi Claire, I literally just put the book down and I would have to say my immediate impression is that after a long year of editing, I shouldn’t have read a book where the main character is an editor. But more broadly, I found that I was absolutely gripped by a third of the book and found my mind wandering and questioning for the other two thirds. What about you?

Claire: I wondered if you’d feel seen by the descriptions of editing and creating a style guide – even though it’s so specific to James and his job as editor at The Royal London Journal of Medicine (fictional place, but based on a real journal where Shuker worked). Like you, I found I really had to read this book. A few times I went back and re-read passages where I felt I’d missed something important, or linguistically dense. But the overall arc of what the hell is James doing and the constant threat of violence had me entirely hooked. Then I started reading deeply into this idea of editing and now wonder if I’ve gone too far…

Mad: I enjoyed the nods to language and its fickle nature throughout but I think actually those would be more interesting to readers who’ve never had to think about commas before. I also found myself having to re-read something because I was sure I’d missed something. But more often than not, I hadn’t, which would be my main gripe with the book (getting straight into it here). The office setting, ostensibly the “clever” parts, felt much more style over substance, but then maybe that’s the whole point when the protagonist edits the style guide?

Claire: I think this is exactly where I got to – the book, while being extremely realist a lot of the time (passages like this: “‘Ha ha,’ he said, then at some kind of rest and with not a trace of bitterness in his voice, he put his cup in the dish-rack and the scrubbing brush across the backs of the hot and cold taps where it always lived, and said, and his New Zealand accent was very strong and he sounded quite small, ‘Weird, eh.’”) is also very slippery and strange and surreal things happen: like mystery floods that disappear, and a mystery dog that appears to be watching over James’ baby (his wife has died; he’s a solo dad). The story almost disintegrates in parts and flips into different perspectives (we even get chapters from baby Fiona’s point of view) which then made me think that James is entirely controlling this story and editing bits out – like his wife who we never meet or even learn her name. I found the linguistic style thrilling, once I concentrated on it, mainly because it is so unique; but I found I had to justify it by thinking – this is all James manipulating how we’re seeing his life choices, and his life.

Mad: See, this has revealed my fear that half the novels I read, I completely miss the message. But in my defence, the blurb on the back literally begins with “equal parts workplace comedy, home invasion thriller and literary conundrum” so that’s what I was expecting. I loved the home invasion thriller thread, and were the literary conundrum aspect simply folded into that as a nod to his day job I’d probably have enjoyed the technique a lot more, but the workplace comedy really lost me and therefore diluted the cleverness of the quirky style aspects and left me wishing the book was just a thriller.

Claire: I did get flashes of The Office, particularly with the two Davids who cracked me up, but I agree, the parts that I couldn’t turn away from were the danger/thriller bits and the total alarm when he goes for a run and LEAVES the baby. That is a mild spoiler – apologies – but for me that insane decision is the heart of the whole thing. James is not okay and I think the rest of the book almost works to hide why – what happened to his wife? We know there was a medical incident at the point of Fiona’s birth but the details, and James’ grief, is buried at the back of the story. I think that’s what made the technical medical language (as a result of his job) so compelling and almost cruel – so much is articulated, but not the biggest, worst thing in James’ life.

Mad: OK this is where I have either figured out the ironic reason for not liking parts of this book, or where I realise I’ve responded exactly as Shuker wanted me to. There were parts where Shuker inserted grammatical errors and typos when James is recalling writers who submitted errors in their work. When the first one popped up I thought, “wow, isn’t that fitting”, and then by the third one I realised that was the whole point. We as readers getting to think in the same way as James.

So then later when Annabel (another of the seemingly dozen named characters in James’s office – another mild gripe of mine) ponders her own writing and specifically the difficulties with how they began – “like a drunken actor moaning themselves out of a nightmare” – it made me wonder if my own earlier thoughts that the first 50 pages should have been cut to 10 was simply playing into Shuker’s game.

Claire: Oh, I feel alive. This is very good. Shuker is very precise – and strings the tension out perfectly – I suspect you’re right and you did fall right into the meta loop. That passage of Annabel’s killed me. It describes, freakishly accurately, how I feel, often, about writing. The lumbering horror of the start before you’ve managed to wrangle it. URGH. Too close.

What did you think of London as a setting / character? It’s 2011, after the 2008 financial crisis, and there’s a distinct dystopian vibe to it.

Mad: Before I answer the London question I do have to note that if I did fall into the meta loop, that’s essentially me saying “I thought the first quarter of the book was boring” and the response is “a-ha! That’s what you were supposed to think!” I’m not sure that’s any better, but please do note I used the correct spelling of “a-ha” as detailed in James’s style guide.

Anyway, London. I enjoyed the dystopian descriptions of it, even as someone who’s never been to Europe, let alone London, and has no familiarity with the geography. As I was reading, I imagined the view from the journal offices as always being overcast, wet-but-not-raining, and somehow a little fuzzy.

Claire: Just before I respond to London – I agree the first quarter of the book takes work, but the first page has a succinct hook – this bit: “The morning of the night he would abandon his child, James Ballard, 38-year-old copy editor, recently bereaved husband and father of one Fiona Beatrice Ballard, aged six months and not much more, rode a quiet post-9am bus to work in Bloomsbury.” No boozy moments there.

But London – yeah I had Slow Horses in my mind. The sense of a sprawl but a certain shabbiness about it. I really liked the hyper-specific descriptions of streets, parks, takeaway spots. It landed me right in there. Likewise, so did the descriptions of parenting and looking after a baby. The “Weet-Bix smell” stopped me in my tracks. Babies really do smell like Weet-Bix. For me, some of the best parts of the book were the passages describing James and Fiona – they felt especially true.

Mad: *Puts away hater hat for a moment* Yes! I was totally immersed in James’s life whenever he was at home. It felt like – again, perhaps intentionally – those were the times when he was without pretence, even internally, and actually evoked feeling from me in response. His fear and anxiety about, well, everything was gripping. I could have spent another 200 pages finding out how he handled the quite terrifying threat of angry local teenagers.

Claire: Those teenagers were terrifying. Shuker does character so well – from clothes to dialect. But I found myself re-thinking those boys by the end. I didn’t trust James as much by the time I finished the story. There is so much left open in the novel – one of these books that wants to linger with you after you’ve finished it – whether out of frustration or mystery, or both.

Mad: Yeah, I found the final chapters suddenly sped up and I thought there would be either a big reveal or a big pull-back but it kind of landed in the middle. I closed the book more impressed than I was halfway through but definitely frustrated.

Claire: So, would you recommend The Royal Free? If so, what caveats would you place around your recommendation?

Mad: I think… no. But this is also the first Shuker novel I’ve read. Perhaps readers with more context around his style and approach would not be so shaken by it 30 pages in as I was. My caveat for this is that I’m very tired and my editing brain defaults to highlighting passages I think could be cut so maybe if I’d read it next week while on holiday, my review would be very different. Again, Shuker makes this point himself when describing the different writing styles of authors for the journal, and the editors’ jobs to polish the edges and, in effect though they try not to, make it uniform. Shuker clearly has a singular prose style – it’s one that I can respect in its execution but not one that I personally gravitate towards when reading for pleasure.

Claire: Fair enough! I ultimately felt jazzed by this book – invigorated by the tension and dazzled by the language so I would recommend it to people who I know for sure are not after a light summer read. And Slow Horses fans. Probably also parents – but after they’re done with the hazy early years.

The Royal Free by Carl Shuker ($38, Te Herenga Waka University Press) is available to purchase from Unity Books.