The latest in a semi-regular series that breaks down a poem to analyse what it’s really trying to tell us.

I’ve been interested in Richard von Sturmer’s work since I saw him perform at Wellington’s LitCrawl years ago. He was compelling, using his whole body to thump out a poem, kind of stamp it out with his feet, and held the crowd (who were squished into Alastair’s Music on Cuba Street) captive. Von Sturmer was in a session about songwriting because, famously, he wrote the lyrics to Blam Blam Blam’s ‘There is No Depression in New Zealand’.

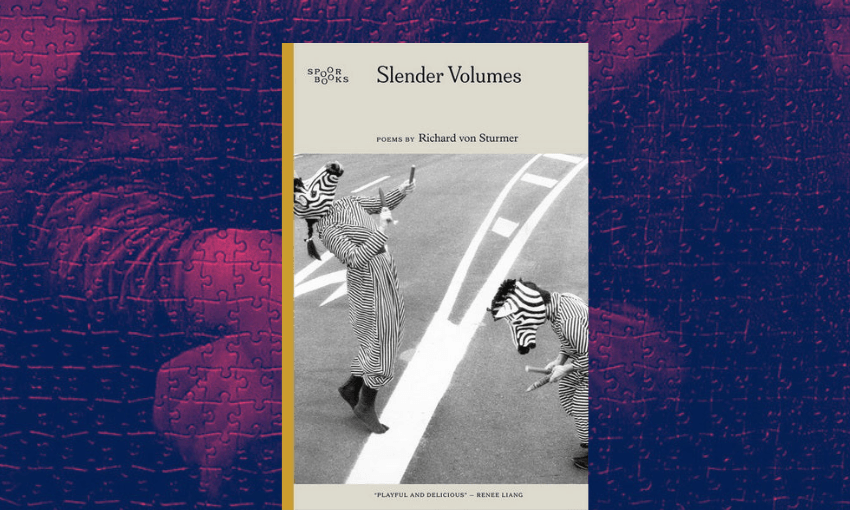

This latest collection of writing is his 10th book and the first to be published by brand new indie press, Spoor Books. Slender Volumes is a series of 300 seven-line poems that respond to 300 kōans, which are, as von Sturmer explains in the introduction: “one modern Zen teacher, Robert Aitken Roshi, described kōans as ‘the folk stories of Zen Buddhism.'” Von Sturmer goes on to say: “There is a paradoxical kernel to each kōan that cannot be accessed by the rational mind; you have to ‘see into’ a kōan by engaging with it on a deeper level, and this process needs to be undertaken with the guidance of a Zen teacher.”

This gives us a clue as to how to approach the seven-line stories in Slender Volumes: we should look deeply into each one but we shouldn’t expect to “understand”, or solve, them. The purpose is to let each verse find a space in our minds and see what it might illuminate there. Useful to know, too, that von Sturmer is a Zen teacher (and manager of the Auckland Zen Centre) so in a way we can read his poems as a sort of poetic guide to the places we can go with this style of storytelling.

I’ve chosen poems 103 – 105 to look into.

103. YANGSHAN’S SUCCESSION

I used to believe in continuity, but now I’m not so sure. The black

swans that populated Lake Pupuke in my childhood were virtually

the same black swans that float on the lake today. They still

defend their territory, perform their mating rituals and produce

their pale grey cygnets. However, a time may come when the lake

falls silent and the words, written in a medieval bestiary, take on a

new meaning, “Who on earth ever heard of a black swan?”

Reading notes:

The phrase “I’m not so sure” in that opening line reflects this idea that we aren’t supposed to be looking for certainty here. The jump to the image of black swans on Lake Pupuke is surprising but it works to expand on the idea of continuity by considering memory: “The black swans that populated Lake Pupuke in my childhood were virtually the same black swans that float on the lake today.” This simple sentence becomes complex: it can’t be exactly true in the scientific sense that the swans of the past are the same as the swans of the present, but can it be true in the philosophical sense? If the habits and behaviours of swans of the present (the poem describes how they defend their territory, and breed) are a simulacrum of the past and also the future (unless swans start genetically mutating) then the “virtually the same” rings true. So you could take it that in this poem the black swan is a metaphor for memory and continuity. Except, we know this is a poem about being uncertain about continuity, and therefore uncertain about the swans.

The last lines reinforce this by moving back and forwards in time: “a time may come when the lake falls silent” is a future concept. But these lines – “the words, written in a medieval bestiary, taken on a new meaning, “Who on earth ever heard of a black swan?” – mark a historical moment. In the notes for this poem, von Sturmer shows that the question is from a translation by T H White of a real medieval bestiary called The Bestiary: A Book of Beasts. The indignation over the existence of a black swan expressed by medieval authors of the bestiary gave rise to the term ‘black swan theory’, which is the theory of unforeseen but impactful events. The placement of this question, and the Medieval mind, in the poem marks a time when black swans were outlandish, unimaginable as a commonplace sight on a lake in New Zealand.

This is a circular poem: the presence of a black swan in the near past (von Sturmer’s childhood memory) triggers thoughts about the present, the future and the distant past and how different those times were, are, or might be, in their treatment of the humble black swan. It makes you think about the brief moment in which you’re alive and how what is truthful to you within that time is not necessarily truthful along the continuum of time: for some, the black swan lives in a local lake, for others the black swan is a nearly impossible event. And that makes the whole concept of continuity uncertain.

104. DESHAN’S ENLIGHTENMENT

It happened when his teacher, Longtan, blew out a candle.

Darkness. No teacher, no teaching, no hand, no flame. Coal black,

bible black. Dylan Thomas and all the poets gone into that

darkness. Rilke as well. Not even a sprinkling of starlight. Then a

lamp is lit, and the traveller, after a long journey, is shown his bed.

Extra blankets are taken out of a wooden chest. And before he

falls asleep, he listens to the horses snorting in the stable below.

Reading notes:

This one has the stuff of a novel brewing inside it. There’s a traveller and a teacher and a cast of poets disappearing into the night (‘black’ from 103 continues here but with a totally different meaning).

Should we take the teacher and the cast of poets as metaphors for knowledge? If we do, and the light goes out and they disappear, what knowledge are we left with? The traveller is left only with the option of listening and sleeping. The information that remains available to him is contained within the sense of sound: the horses snorting; and in sight (his own impending darkness); and in touch: the sensation of his body lying down, covered in blankets.

After the complexity over the concept of continuity in 103, 104 feels like a welcome rest. A pause before the next entanglement in ideas. There’s also a fun play on the word enlightenment – it’s an endarkenment that happens (but if the candle hadn’t have gone out would he have fallen asleep to the sound of horses?)

105. THE HANDS AND EYES OF GREAT COMPASSION

I bought a jigsaw puzzle of the Mona Lisa for five dollars at a

second-hand shop. The reproduction was yellowish and several

pieces were missing. While doing the puzzle, I was drawn not to

her eyes or smile, but to the delicate fingers of her right hand,

slightly spread apart and resting on her left forearm. I noted that

her hands were warmer in colour than her face as if she had been

washing clothes next door before coming in to sit for Leonardo.

Reading notes: I love how kitsch this is. A jigsaw puzzle of the Mona Lisa is symbol of our mechanical, commodified times. Great art is reproduced for play. It can be pulled apart and remade. But here the poet is looking closely at the painting in a way that wouldn’t be possible without this deconstruction and reconstruction. The form of the puzzle helps the poet really see the Mona Lisa: the detail of the hands isolated as they are within a piece of puzzle. The poet notices their colour and mood (the resting pose) and through this noticing the poet gleans another way to read this great work of art: that the deeper colour of her hands signals exercise and the realisation that she might have been engaged in labour right before she had to sit for the artist.

The poet imagines outside the lines and starts to explore the Mona Lisa, the person, beyond the frame. It’s washing that comes to the poet’s mind, but we might imagine other things: writing, or painting, or arm wrestling, or playing with a dog.

The possibilities are endless. And I think that’s the point.

Slender Volumes by Richard von Sturmer ($38, Spoor Books) is available from Unity Books.