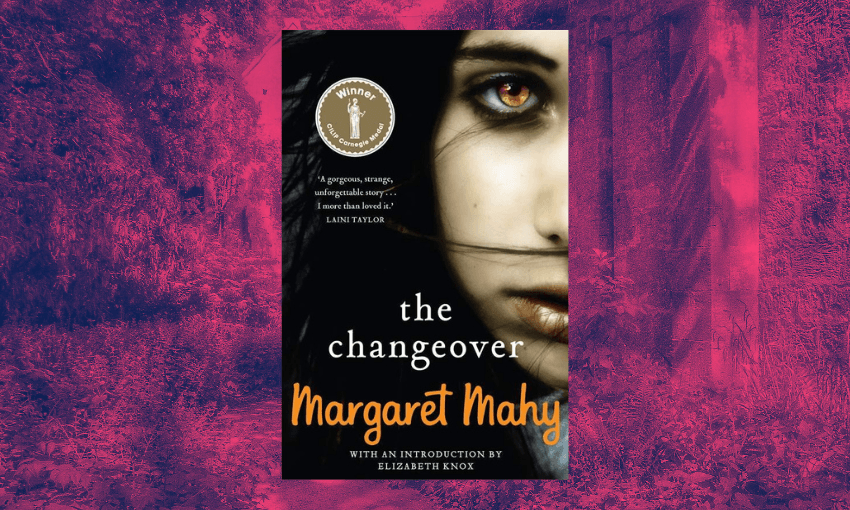

Books editor Claire Mabey sings the praises of Margaret Mahy’s 40-year-old supernatural thriller.

It’s been 40 years since The Changeover by Margaret Mahy was published, and since it won the prestigious international award for children’s writing, the Carnegie Medal (just two years after Mahy won it for The Haunting). Forty years on, and The Changeover is still the best young adult novel that New Zealand has ever produced.

“Again, as in The Haunting (1982), New Zealand writer Mahy proves that all-out supernatural stories can still be written with intelligence, humor, and a fearful intensity that never descends into pretentious murk or lurid sensationalism,” wrote Kirkus Reviews in August 1984.

I read The Changeover most years, and the above assessment is as true now as it was then. Each re-read reveals a fresh and contemporary story, as if Mahy wrote it yesterday. The main reason for this is that Laura Chant, Mahy’s teenage heroine from Christchurch, is as purely and honestly teenage as art can convey. Young people all over the world have identified with Laura for decades because Mahy was so deft at authentic, lived-in characters; so specific they are universal. Around the central spectacle of Laura, the other characters in the book orbit and influence in a complex dance as difficult and beautiful as life itself.

The plot of Mahy’s supernatural thriller is simple: Laura must save her little brother Jacko from being possessed, from being consumed from the inside out, by an insidious demon (disguised as a creepy antique shop owner, Carmody Braque) and so she elicits the guidance of local witch, Sorensen “Sorry” Carlisle and his mother and grandmother (also witches) to help her “changeover” and access her full and innate power, and become a witch, too.

The setting is the fictional Christchurch suburb of Gardendale, where there are kingfishers, and the river, and subdivisions, and fish and chips, and hair salons. In this unassuming and familiar suburb magic and terror collide. It’s the 80s, but Mahy left only scant cultural references to that time – really it’s the absence of phones and screens that signpost the past – and is another reason why The Changeover feels timeless, or suspended like a bridge. Inside this familiarity, otherworldliness flares: the horror of Jacko’s physical decline, the vulnerability of that little boy (a theme in Mahy’s work), and the unsettling transitions of adolescence.

There is the precariousness exposed in this book: the flashes of uncanny foresight that Laura has (she is one of Mahy’s “sensitives”, people who can sense when things are about to happen) is a metaphor for that confusing phase of half-adult, of glimpsing your own possible adult future but not being quite ready for it. In this way The Changeover is about exposure: Laura excavates herself, and those around her, to reveal bald truths about humanity that can only truly be seen once innocence is corrupted, and experience, and thinking about sex, takes over.

Laura’s changeover in the novel — a long, terrific and surprising scene — is one of the greatest ever literary metaphors for entering into conscious desire, a sure marker, if not the marker, of growing up. Mahy cannily flanks and mirrors Laura’s developing inner witch/wise with the clunky stuff of parents: Laura’s mother brings a new boyfriend into their lives (Chris, a benign force), meaning that Laura is confronted with her own mother’s comfort-seeking, her desires, her yearning for love and sex that at first seems alien to the idea of “mother”, but then becomes inextricable from it. And when Jacko is in hospital, the doctors befuddled, Laura’s absent father reappears, bringing with him a pregnant second wife. All the evidence of sex and adult decisions are exposed by the bump.

Mahy is masterful at blending magic into the whirlwind of daily life: Laura’s awakening is the universal story of a person who was once blissfully innocent who has to shift into the inbetween phase of adolescence and face awkward truths about one’s own family and their personal, private lives. When Laura undergoes her changeover it is a forever departure from who she was before: what is seen cannot be unseen and that knowledge transforms you forever. And this is all hinted at, ingeniously, from the very beginning of the book.

This is the opening of The Changeover: “Although the label on the hair shampoo said Paris and had a picture of a beautiful girl with the Eiffel Tower behind her bare shoulder, it was forced to tell the truth in tiny print under the picture. Made in New Zealand, it said, Wisdom Laboratories, Paraparaumu.

“Just for a moment Laura had had a dream of washing her hair and coming out from under the shower to find she was not only marvellously beautiful but also transported to Paris. However, there was no point in washing her hair if she were only going to be moved as far as Paraparaumu.”

This opening never fails to delight me for two reasons: the first is that I distinctly remember having very similar thoughts in response to shampoo ads and their promises of transformation; and the second is that it’s funny. Laura’s wry realism — that nonchalant, hopeless sort that teenagers do so well — rubs up against her desire to change, and this is the very heart of the novel.

The beginning also carries the whiff of Mahy’s particular sort of mundane magic: the extraordinary happens in this book, a young woman becomes a witch through a heady process complete with herbs and mulled wine, a drop of blood and a mirror, but it is secondary to the regular trickiness of life and how circling closer and closer to the adult world casts both shadows and excitements. You can’t get more banal than shampoo. But in Mahy’s hands it speaks to a regular girl in a regular place who might just have a very interesting story. In Mahy’s novels for young adults, magic always erupts from ordinary-seeming people, which makes her storytelling sublimely relatable. We all want power and Mahy gives it to us, no matter how poor, or troubled, or ordinary we might be.

Sorensen Carlisle, the teenage boy, prefect and “secret witch” to whom Laura goes to for help, is one of the most charismatic and curious characters in Mahy’s body of work, which is saying something. He lives in an old house called Janua Caeli (Gate of Heaven) that has fairytale qualities – a house built before the subdivision of Gardendale grew around it, a symbol of a time before, of difference. As a teenage boy he is capricious, brazenly flirtatious, and curiously old-fashioned in his capacity for swotting: like a professor in a mahogany study. When Laura goes to Sorry for help, and outs him as a witch, he says: “What do you want? … I might provide a love philtre but I don’t do contraceptives.” Sorry ushers Laura and the reader into the tensions that come with the possibility of sex.

As the pair grow closer, and as Jacko’s condition deteriorates and the need for Laura’s changeover intensifies, Sorry exposes more and more of himself: his tragic beginnings, an abusive foster father, a stutter a symbol of his uneasy burdens. Mahy paints Sorry like an art work and then Laura unravels his meaning: “Do you think there are any private moments in art?”, Sorry asks Laura in their first scene together. This is Mahy’s genius: a supernatural thriller that is grounded in the questions of fully fleshed characters, how the teenagers work upon each other, articulating themselves with greater honesty as they go, and questioning everything, like spells.

The Changeover is relentlessly luminous, dark, thrilling and beautiful. And its potency hasn’t diminished one bit. Carmody Braque is a satisfying sop of a demon (or more technically, a lemure) in the end. Once he realises his mistake – that Laura is powerful after all – he tries to offer money and holidays in Greece (“the Isles of Greece where burning Sappho loved and sang, as Shelley says”) to stave her off; and like the worst of them, calls her a bitch in his last, lame attempts at stealing life. Laura’s final act of undoing for the predator is to identify Braque as “an awful idea that’s got himself a body it shouldn’t have.” It is extremely difficult to think of a writer who gives teenagers as much agency and brilliance as Mahy.

In the very end, The Changeover is a novel that rumbles around ideas of consent, and the heady illogic that is the working out of the differences between desire, romance and love. Carmody Braque’s presence in our world hinges on his being invited in to experience the sensations of being human: “to feeeeeel…” are his last words. And once the danger is over, and Sorry Carlisle and Laura Chant turn their thoughts back to the usual teenage preoccupations, like exams and what to do after high school, Sorry wrestles with his desire for Laura: “Let’s go through to your room now … Come on, Chant! Invite me. If you think I’m doing the wrong thing tell me what you want and I’ll do what you say.”

The teenagers are so intimate with each other now, so honest, that Sorry goes on to say he’s unreliable, and Laura says she thinks she loves him: “So maybe that’s what makes the difference.” Timeless.