This time the challenges are different, writes Duncan Greive.

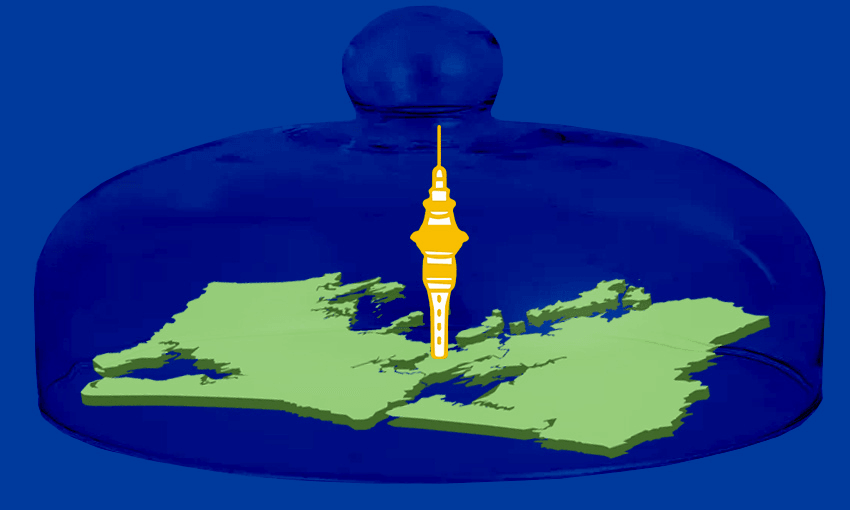

From this morning, we enter a new phase of the pandemic. We have a country from roughly the Bombay Hills south which is on the road back to recovering its freedoms – hardware stores are open to tradies, you can get a flat white this morning and takeaways tonight, and healthcare systems will start to operate more normally. Northland is poised to move to level three on Friday, leaving greater Auckland as another country, likely to be stuck fast in level four for some time yet.

A large majority of us understand why that is, and polling shows support for lockdowns remains as strong as ever. Yet what we’re entering is a new and different phase of the pandemic from a social and economic perspective, one which brings with it complexities we haven’t had to contemplate until now.

Put simply, the country is going to cleave in two in a way it hasn’t before, and that gap could grow if (as seems likely) the lockdown and its aftermath drags on longer than current signals suggest. The implications for communities, for business and for students are real and will require thought as to how they are managed, both during the outbreak and beyond. This is fundamentally a different situation to the lockdown of a year ago. Yes, Auckland was in a different setting, but it was able to defeat the virus at alert level three, thus allowing much of its life to go on.

Now, policy responses will accordingly be far trickier than those which have come before. Here are some of the challenges that face us now, and that will become even more stark when, as seems inevitable, large parts of the country enter level two or 2.5.

People will start to have different health outcomes according to where they live as the majority of the country starts to open back up to elective surgeries and other non-acute care, while Tāmaki Makaurau remains under level four restrictions. If you’re waiting on surgery, which may well have already been delayed under prior lockdowns, another postponement of indeterminate length will be hard to take.

Of course, divergent health outcomes according to geography and ethnicity have long been a feature of our health system. But a prolonged level four lockdown in a high-needs area further exacerbates those issues. There are ways of addressing this in future, such as by bringing in medical staff from around the country to work through a backlog. But this would be poorly received by the area loaning the resource, particularly during a period characterised by unmet shortages of doctors. As it goes for physical health, so it goes for mental health: consults done online or over the phone, and fewer acute beds available, during a time of high stress within the community.

A large group of Aotearoa’s students could have in-person learning, while another large group will be online-only. The difference to education between levels three and four is largely immaterial for those in school. The big change comes a level down, when around 470,000 of our rangatahi will have the ability to return to in-person learning, while the 290,000 in Auckland will remain at home.

Already we have seen cancellations of preparatory exams. If this outbreak drags on for weeks, as experts predict, we will see a significant reduction in classroom time during the crucial lead-in to exams. For many Tāmaki Makaurau students in the final years of high school, it marks a second consecutive year with at least a month lost at this time of year. It’s not just the time lost either – the scars of lengthy lockdowns linger in lower decile schools, where chronic absenteeism increased markedly among deciles 1-4, while being flat in deciles 7-10.

This has been attributed to factors like multi-generational living, which amplifies the risks associated with contracting Covid-19 for whānau; and economic hardship changing working conditions, forcing older children to stay home to care for younger siblings. But irrespective of what drives it, what is undeniable is that a hard and very necessary lockdown will have a disproportionate impact on one city, and on particular communities within that city. These are potentially scarring events which could impact qualification for tertiary study, and future employment outcomes for years to come.

Competing businesses will have very different abilities to trade depending on where they are headquartered. The most obvious benefit is to large national businesses, which can sell into our biggest city from stores and distribution hubs located elsewhere. MBIE confirmed to The Spinoff that consumers in level four can buy products from level three retailers, “so long as the alert level three business or individual is following the alert level three rules”. Couriers and freight company employees can cross alert level boundaries.

What it means is that small businesses already strained from multiple lockdowns face the prospect of ceding customers to competitors from outside the region, particularly national chains able to leverage their scale and locations to sell into the city from beyond its boundaries. This plugs into accelerated, long-term shifts to online shopping, and increased use of customer databases in highly sophisticated ways.

For example, if you sell homeware from a single shop and related online operation based in an Auckland suburb, from today your customers cannot shop with you, but remain stuck at home. If they transfer that business to a national retailer, or even a similar independent business outside of the city, they are also likely to register an account and join an email database. In this way a single transaction can predict a customer lost for good.

This impacts multiple industries, from screen production to manufacturing. Even construction is almost entirely paused, meaning developers based in Auckland will lose ground and momentum in addressing the big overarching crisis of our time in housing. Many of these transactions and relationships are harder to shift than an online shopper, but the fundamental barriers to commerce being unequally distributed between regions is a reality we now face, with the potential for that to extend and compound.

Remember these things about Auckland: demographically it is younger, more diverse (Tāmaki Makaurau has higher Pacific, Asian and MELAA populations than Aotearoa as a whole) and has the highest housing costs of the country. Therefore these issues will be disproportionately visited upon some communities which start disadvantaged – and are often our essential workers, too. Where jobs are transferred from Auckland to other centres, they inevitably hit those communities hard.

This was masked during the first lockdown by its national nature, and during that of August 2020 by being staged at level three, and its relative brevity. This one is already shaping as very different, yet to date the policy response is the same – the wage subsidy and various other levers, largely created and refined a year or more ago.

They worked for a triage, though the great wage subsidy rort remains an aching and unaddressed sore. This next phase we’re staring down brings with it far more complexities to solve.

Level four is manifestly the appropriate response to the extraordinary challenge of delta in our community. And it is equally appropriate that the whole country should not suffer unduly when the virus can likely be contained and confronted within a single region. But it’s clear that from this day on, the national interest in defeating the virus weighs disproportionately on one region alone, and particularly on some communities within it.

It demands that this government rise to meet that with some appropriate and targeted response for the extra burden borne by the city – and particularly some of its most vulnerable populations – in suppressing this outbreak.