Summer reissue: In a leafy park in Queenstown, George Driver discovers why New Zealand produces the best tree climbers in the world.

First published November 16 2020

I could hear them before I could see them. The sound of a dozen people hollering rolled across Lake Wakatipu.

Entering Queenstown Gardens I soon found the source – a group dressed in fluro shouting at a tree.

Then things got stranger.

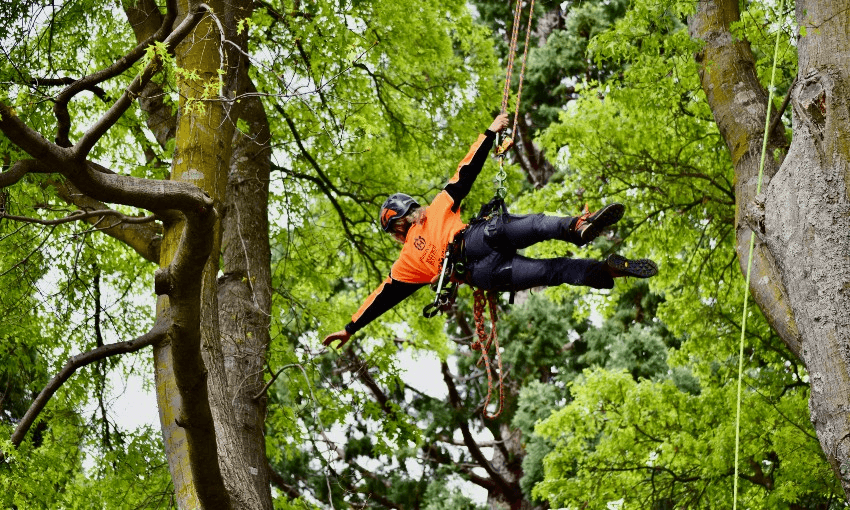

Inside the tree a man was dangling from a rope and swinging from limb to limb, intermittently stopping to ding a bell with a saw or throw sticks at a basket on the ground 10 metres below.

After three minutes of this highflying performance the man dropped onto a circular platform at the foot of the trunk and the crowd erupted in applause.

This was my introduction to the world of competitive tree climbing, a sport few New Zealanders have heard of, but really should have.

New Zealand is good at climbing trees. We hold the international title for men’s tree climbing and New Zealanders have dominated the sport for the past decade. We’ve won 11 world titles in that time making us arguably better at tree climbing than cricket or rugby.

It also has all of the elements of a great sport: danger, skill, chance and a spectacular setting. That weekend, twenty-seven competitors (seven women, 20 men) had gathered on a leafy peninsula on Queenstown’s Lake Wakatipu for the pinnacle of the domestic sport, the National Tree Climbing Championship. Organised by the NZ Arboricultural Association, the event brings together the most talented climbers in the country, all of whom have developed their skills and technique by working as arborists, earning their living pruning, planting, removing and caring for trees.

But there is one major barrier to the spectator sport: figuring out what the hell is going on.

Fortunately I had event organiser Craig Webb to guide me through.

“It’s not really like any other sport in the world,” he said.

At first glance it looked to me like a combination of rock climbing, gymnastics, kubb and quidditch. In an interview with Kim Hill, one competitor described it as “in-tree ballet”.

Webb started climbing 21 years ago and has been involved in organising the events for 15 years.

He explained that the first day of the two day competition involves five events, each held at a different tree and designed to test a different skill.

Four of the events are relatively straightforward. There’s the Ascent, where competitors try to climb a 15m rope in the fastest time; the Speed Climb, a good old fashioned timed race up a tree; the Throw Line, where competitors attempt to hook a rope over a tree’s highest limbs by swinging a small weight on the end of a piece of string; and the Aerial Rescue, where they climb a tree to rescue an unconscious arborist – in this case a 75kg dummy – and rappel the body safely to the ground.

The final event, the Work Climb, is more complex, but it is the pinnacle of the sport.

Competitors start near the top of an enormous tree and climb and swing from limb to limb to complete challenges on its far flung branches. At each station they must hit a bell with a saw. One station, called the limb climb, requires dinging a bell hung at the end of an exceptionally spindly branch. A weight attached to a rope is suspended from the end of the branch and dangles into a clear plastic tube and heavy-handed competitors lose points if they disturb the branch and send the weight bobbing. At another station, the limb toss, they must toss sticks into a basket on the ground for points. Extra points are gained for the dismount, where the aim is to land with both feet inside a circular platform. All the while a team of judges stand near the trunk, necks craned to the sky, giving points for style and technique.

It took me a few hours, but I became engrossed. The level of skill on display was exceptional. The best climbers seemed to become a part of the tree, travelling with monkey-like agility, leaping into the air and gliding gracefully from branch to branch. Those less experienced seemed to battle against the boughs – their struggle and hesitation emphasising the extreme height and challenge of the sport.

The biggest name in competitive tree climbing was also watching from the sidelines. Scott Forrest (yes, that’s his real name) is reigning world champion and has automatically qualified for next year’s event. He was there as mentor, having won the world title four times and competing for 22 years.

Webb still remembers seeing Forrest at his first event.

“He had this cat-like way of climbing, this incredible natural sense of balance to be able to just walk through a tree,” Webb said. “He had that from the start.”

Forrest said he took up the sport while studying to be an arborist at age 17, competing as part of his Wintec course. He came fourth in the country at his first national event, engendering a level of self-belief and ambition that would take him around the world.

“Getting a place at nationals at that age, that was pretty mind blowing,” Forrest recalled.

“Now I’ve competed in 30 countries around the world. This sport can be endless if you want it to be.”

While talking he was interrupted by a fan who asked him to film a short message for her son who was starting out as an arborist, to which he obliged with the kind of fluency and charisma you’d expect of an international sports star.

But Forrest wasn’t alone. A number of people I talked to had travelled the world climbing trees.

Jelte Buddingh was national tree climbing champion of the Netherlands and spent years travelling around Europe in a van following the tree climbing circuit and once came third at the world championship. He grew up in New Zealand, but lived in Holland for 15 years, working as an arborist in Utrecht. He started climbing in 1999, won his first event and became hooked.

“I was really shit at school and I finally found out I was good at something,” Buddingh said. “I got a taste for winning.”

Now retired from competing, he drove from Dunedin to watch the competition and was regularly called on by competitors seeking out his advice on tree climbing strategy.

Nicky Ward-Allen started competing because she lied to her boss. She was interviewed for a job as an arborist and was asked “do you tree climb?”.

“I said yes to get the job and then I had to compete,” Ward-Allen recalled.

It was fortunate, because she turned out to be one of the best tree climbers the world had ever seen. She has competed at the world championships multiple times, winning in 2013, and still holds a world record for ascending a 12m rope in 13.26 seconds.

“Winning the world champs was surreal,” she said. “I’d worked for it for so long it was like a dream.”

She became an arborist after seeing an ad for a course in her local newspaper. She was studying a science degree at the time, but dropped out to pursue a career in the trees.

“The ad said there were four jobs for every graduate and you could work out in the field and travel the world,” Ward-Allen said. “I didn’t want to spend my life working in a lab, and arboristry is a mix of brains and using your body. I love it.”

These days arboriculture is a booming, in-demand trade, with about 1600 registered arborists in 2018. However, Ward-Allen was the only woman in her arborist course and when she started competing it was just the second year the competition had opened to women. The sport’s steadily gained a following among female arborists and New Zealand women are excelling at it, winning the world title seven times.

Ward-Allen has now competed at every national competition for the past 17 years. So what keeps her coming back?

“It’s the community. It’s a competition but that’s not the driving force. It’s about everyone helping each other.”

The vocal support the competitors lavished on one another was almost as striking as the climbing itself. That sense of community was something every single competitor mentioned when I asked them why they climb.

“I don’t know of any other sport where you tell your competitors how to beat you and give them the gear to do it,” young arborist Scott Geddes told me. “It’s about the most supportive competition you will ever see.”

Webb believes that’s what makes home-grown climbers the best in the world.

“It’s the local scene,” he said. “It’s a really supportive community with a focus on having role models and mentors.”

For some competitors, that support has been life changing.

Zane Wedding became a competitive tree climber after he was expelled from school at age 16.

“Two days later an arborist, one of the judges here today, came and picked me up, took me to work and I thought this is the coolest thing ever,” Wedding said. “Then one of the workers introduced me to competitive climbing and I thought ‘I could do that’. It’s had a hold on me for 23 years.”

Now he helps other youth find their future in the trees, working as an arboriculture lecturer at Manukau Institute of Technology.

“I brought four students down for the competition and a lot of them had never been on an airplane before,” he said. “Since starting the course in February some have gone from having an ankle bracelet to having a career. Those students had never been in an environment like this. After spending the weekend at the competition I know arboriculture will change their lives like it changed mine.

“This competition gives young people something to be passionate about. And having a world champion like Scott giving them encouragement, it changes their whole aspirations. Now they want to be world champions and I know there are future world champions here this weekend.”

But for Wedding, victory in the sport has remained elusive. He is yet to win a national title.

“This is my year,” he yells out after completing the Work Climb. “I want this more than anything in my life.”

It may help that he has lived in a puriri tree for the past 125 days. He is one of a group of protestors who have occupied native trees in Canal Road in Avondale, protecting them from an impending development. Conservation is part of the job, he said.

“Being an arborist is about kaitiaki for ngā rākau. I teach students that we are the go-between between the community and the trees and the people who are best at that are here today.”

As the day drew to a close a few dozen spectators were lolling in the grass and I overheard more than one volunteer saying it was the best event in years.

It seemed like a victory for the entire country. Scott said it was the only national event being held in the Year of Covid. Queenstown seemed like it had never heard of that five letter word.

I’d last been in Queenstown six months earlier as it emerged from lockdown and faced economic destruction. But it had risen again. The Spirit of Queenstown was back, plying the lake.

Groups of young people, apparently gainfully employed, sat in groups on the waterfront, drinking, slacklining. A stag party of shirt-clad southerners lurched past, the groom-to-be stalking around in a tutu. A high-heeled hens party shivered along in the rising southerly. The kind of scenes that seem as natural to Queenstown as the lake or the mountains.

In the morning the snow was back as well. The temperature plunged to six degrees as I returned to the gardens for the Masters event. The previous day’s competitors had been whittled down to six – two women and four men – who would compete in the final. The Masters is held in a single tree and combines all five of the events of the previous day into one 30 minute challenge designed to push competitors to breaking point. Unlike the heats, they have to start from the ground and set up their own ropes. The separate stations are similar to the Work Climb, but placed in more extreme positions.

Tauranga arborist Steph Dryfhout won the women’s event with apparent ease, methodically working her way around the tree and clinching the title for the third time, beating Methven arborist Sami Baker.

But the men’s event turned into a day of broken branches and broken dreams.

The winner of the heats, Aucklander Sam Smith, was tipped as the favourite. But he never seemed to find his flow. Delayed with technical issues as his ropes became entwined he tried to make up points as the clock ran down but lost his footing on an ambitious jump and swung wildly headfirst towards the trunk, dreadlocks flying. He regained his composure and made it to the limb toss when there was a loud crack. He had snapped a branch. Instant disqualification.

Next was Wedding, who qualified second. With the games’ leader out of contention could this be his year? He set his ropes quickly, making good time and went straight to the limb walk. As he edged his way towards the bell at the end of the branch there was a crack and he plunged out of the tree, swinging impotently above the ground, the four meter severed branch still in his hand, the bell still just out of reach. Disqualified.

“I’ve never seen that happen in a competition,” exclaimed one onlooker.

Absolute scenes.

The judges grouped coyly – did they set the station on a branch that was too fragile? Wedding looked dumbfounded, unsure whether to laugh or cry, but was soon greeted by his fellow competitors in commiseration.

Another finalist, Sam James, also couldn’t catch a break. He got stalled at the first step, his throwline getting caught by a snag. The crowd yelled encouragement and advice but the battle with the rope stretched on for 20 minutes of teeth-clenching tension. Finally he abandoned the rope and set a new line over a lower limb to try to get points on the board. Then there was another snap and a small branch floated from the tree. Three competitors disqualified. Devastatingly it was the third time he had competed in the Masters and had been foiled by a snagged throwline.

Dunedin arborist Dom Ritter won the men’s with ease, methodically completing all of the stations to join Steph Dryfhout and Scott Forrest at the world championships in Copenhagen next year (Covid willing).

As for Zane Wedding, he will be back again next year.

“I’ve worked for this for 23 years,” he said. “There will come a day when I will have my chance again.”

Independent journalism depends on you. Help us stay curious in 2021. The Spinoff’s journalism is funded by its members – click here to learn more about how you can support us from as little as $1.