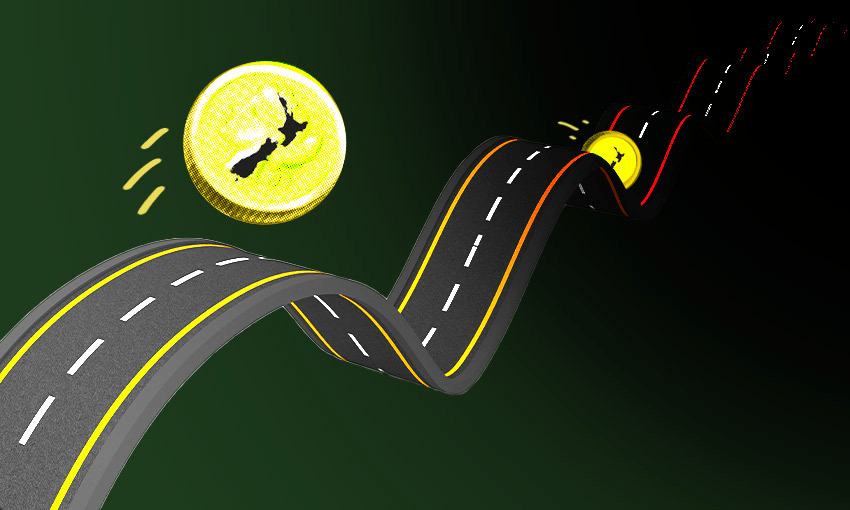

While Aotearoa emerged out of last year’s lockdown recording world-leading economic growth, the country’s pathway through the pandemic is becoming murkier. The next 12 months may be far different to anything we’ve experienced.

Last year, as the pandemic raged around the world, New Zealand achieved something of an economic miracle. After the harshest lockdown in the world, the country bounced into an economic recovery in the absence of Covid-19, experiencing the largest leap in economic growth on record.

Buoyed by national pride and existential relief we spent like no tomorrow. Interest rates were at record lows, government stimulus at record highs and unemployment dipped so low that economists said it was unsustainable. For the property-owning majority, whose assets rose in value by nearly a third, life was good. Vaccines were being developed and there was talk that if even just 70% of the country was vaccinated the virus would be defeated by herd immunity. As recently as February, Dr Ashley Bloomfield wrote that he hoped the country would achieve herd immunity “later in the year”. We simply had to wait it out in paradise. We watched the horrors of overseas – the death and never-ending lockdowns – from our snug, smug cocoon at the bottom of the world.

Over the past year, if anything, the economy gained momentum, as we became one of the first countries to record GDP growth beyond pre-pandemic levels. Pundits said the biggest risk was that the economy was overheating, as inflation hit the highest level in more than a decade.

There were a few cock-ups at the border, but small outbreaks were dealt with relatively swiftly and successfully, strengthening our resolve. A delta case rampaging through Wellington in June didn’t result in even one other case – the country seemingly saved by a single vaccine dose.

But now, as Auckland enters its fifth week in lockdown, it feels different. Whereas the first lockdown provided a neat bell curve of cases – with a comfortingly predictable decline – delta’s long tail is hanging over the country’s biggest city like a dark question mark. As the rest of the country reopened to level two last week, the response seemed more subdued. People stayed home.

And whereas last year the prospect of herd immunity through vaccination provided a clear light at the end of the tunnel, now things are murky. With the rise of delta, herd immunity has turned out to be a mirage. Now there is no easy – or clear – way out. In the pandemic-ravaged world, the trade-off is easier. High vaccination rates have brought deaths and hospitalisation rates down to more palatable levels. Most still experience deaths every day, but that looks like success after hundreds or thousands of daily deaths, and now they are opening up and removing restrictions. But our early success makes for a far different equation. After a year of Covid-zero, choosing to have a couple of deaths a day seems unconscionable.

But then what? Will periodic lockdowns be required indefinitely to keep Covid at bay? And will the vaccinated majority be as compliant with lockdowns to protect our unvaccinated peers? As a successful short term measure, New Zealand has embraced the lockdown like no one else. But as an indefinite disruption to life, how long will the public support them as the rest of the world resolves to live and die with the virus? It feels like there is no clear end-game now. The light at the end of the tunnel is flickering.

These question marks also hang over the economy. John McDermott is executive director of economic research institute Motu and former chief economist of the Reserve Bank. He says this recovery will be different. Whereas last year, Covid-19 appeared to be a temporary shock and many believed the worst was over, now there’s a growing belief that we will be dealing with the virus indefinitely.

“Last year we eliminated Covid. That allowed people to confidently go about their daily lives, and engage in economic activity and enjoy themselves without risk, so our economy did relatively better than other economies,” McDermott says. “What we are going through now with delta, the whole effect looks to be endemic. Covid-19 is going to continue to be with us – it’s not going to be a temporary event. So how do we reopen? How do we move forward?

“This got into New Zealand from one limo driver in Sydney and managed to explode in Australia and slip through New Zealand’s MIQ and it’s proven very difficult to get rid of. We’re still seeing cases now increase even after four weeks of lockdown.

“Now the challenges are much bigger.”

As awareness that the circumstances of the pandemic have materially changed for the worse, he says that unlike last year, people will begin to tighten their purse strings.

“Even if we beat it this time, which is hopefully true but not assured, we’re going to be confronted with these incursions on an ongoing basis, so it’s no longer a temporary event. So it looks like our activities, our productivity, our labour market are all going to be affected in a much more permanent way. And when it’s a loss of permanent productivity and a loss of permanent output, then the rational response from consumers is to actually not bounce back and spend the savings we had from lockdown, but to be cautious about your spending from this point onwards.

“We will bounce back, but I think the ongoing recovery will be much more subdued than in the past.”

But for now, business appears relatively upbeat. ANZ’s Business Outlook survey for September showed business confidence was up and business activity was far more resilient compared to last year’s lockdown. NZIER’s Consensus Forecasts for September found household spending intentions were strong, although growth was expected to be lower. ANZ and others expect GDP to take a 6% hit from lockdown – half the 12.2% dip brought by lockdown last year – and household incomes will be relatively unaffected due to the wage subsidy. After lockdown, the major banks by and large expect the economy to plough on like before. With the borders closed, unemployment is expected to remain low so people will feel confident dipping into their savings, knowing their jobs are secure, and may feel emboldened to ask for a raise.

In fact, too much consumer demand, not too little, is viewed as the bigger risk to the economy. The major banks are still predicting the Reserve Bank will hike interest rates next month, in a bid to dampen down high consumer demand to rein in inflation.

But all of the forecasts are overshadowed by the uncertainty of Covid-19.

“We simply don’t yet know how long-lasting the outbreak will end up being (especially given how infectious delta is), and we don’t know whether the economy will be able to shake off the impacts of lockdown in the same way it did in 2020,” ANZ said in its recent Quarterly Economic Outlook report.

The ANZ report also suggests there is less in our favour this time around. There won’t be the same combination of rising house prices and low interest rates that provided the impetus for growth last year. Economic growth overseas has also slowed after a post-lockdown rebound and delta has created more uncertainty. On the other hand, it says the buoyant economy heading into lockdown and the more resilient economic performance during lockdown provides hope for ongoing growth.

“So hopefully these will be enough to get us back on track. But ultimately, it’s down to the path of the virus,” the report said.

But McDermott says the uncertainty of the country’s pathway forward – to continue elimination with the risk of ongoing lockdowns, or to “live with the virus” – will eat into people’s spending habits and business confidence.

“Business confidence may well still be positive, but can it remain positive when reality starts to hit?”

However, some believe the country’s pathway through the pandemic is looking bright. Victoria University research professor, and director of the Malaghan Institute of Medical Research, Graham Le Gros says Covid booster shots could revive the possibility of herd immunity – or community immunity. There could still be light at the end of the tunnel.

“We will be educated by the right kind of booster shot that will nail this virus dead,” Le Gros says. “Other countries just had to get the vaccine out any way they could. They were under enormous pressure because people were dying. But they are doing studies of what a third booster shot does and even three doses of Pfizer gives you such a high level of immunity, it really makes it very difficult for the virus to do what it’s been doing.”

With some ongoing restrictions, we could avoid lockdowns and start reopening to vaccinated travellers, he says. “With 80% vaccinated and with the delta virus, which the Pfizer gets quite effectively – it stops sickness and hospitalisation – we could hope for a pretty minimal impact. We can have a measure of level one or level two with social distancing and that puts pressure on the virus, so you can have community immunity.”

But the country will need to accept a change, he says. “We will have to accept more cases and more deaths … We’ve been told no death from Covid-19 is acceptable, but there are other health effects emerging from these lockdowns that are also devastating.”

Even if the country vaccinates 80% of the population, however, vulnerable communities would likely face an outsized impact were lockdowns to be abandoned in response to community outbreaks. Vaccination rates for some age cohorts of Māori and Pasifika are a continuing cause for concern, with questions being raised about whether public health authorities have got the strategy right. It has been estimated that even if 90% of the total eligible population was vaccinated that could mean a third of Māori were still unvaccinated.

Dr Rawiri McKree Jansen, director of the National Hauora Coalition, a Māori primary healthcare organisation, has said that inequity in health is such that we shouldn’t think about opening the borders until Māori vaccination rates reach 90%. “Until vaccination rates in the order of 90% of eligible Māori are achieved, opening of the borders would likely be catastrophic,” he said.

Jacinda Ardern has also said this week that lockdowns won’t be used long term as vaccination rates increase. If high vaccination rates prove effective at clamping down on future outbreaks, we may be able to continue to bide our time and learn from others. She says the plan for reopening our borders to vaccinated travellers from low risk countries next year – along with ongoing elimination – remains in place.

But can we still pull off ongoing elimination without lockdowns while liberalising the border? The next 12 months will be the biggest test. We will find out whether we can still keep Covid-19 at bay, or if our pandemic just beginning.