Last month, Mt Eden restaurant Hees Garden closed after more than four decades of operation. Former owner Wynsome Wong tells Charlotte Muru-Lanning how the restaurant’s story reflects a period of remarkable transformation in New Zealand society.

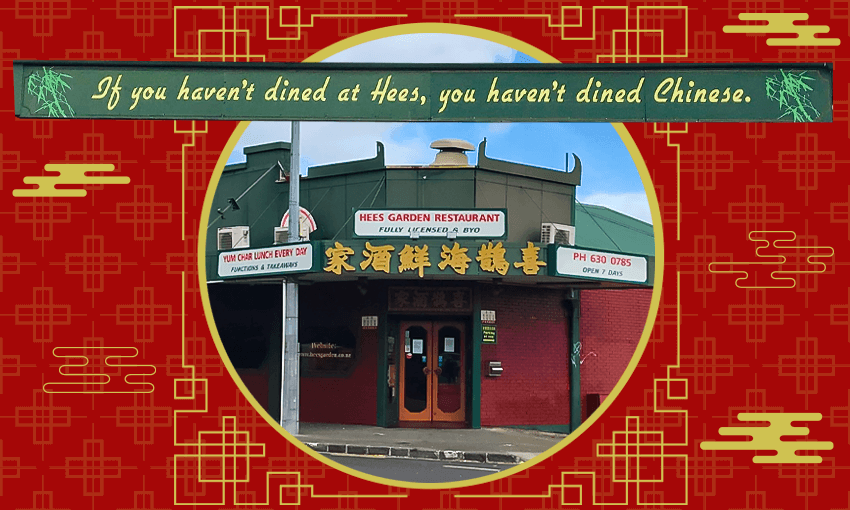

With its octagonal green windows, red brick facade and details mimicking the up-curved eaves of classical Chinese architecture, Hees Garden stood out in the leafy, villa-filled Auckland suburb of Mt Eden.

After 41 years serving a variety of regional Chinese food, Hees Garden closed its doors for good last month. The building is being demolished to make way for a planned apartment development.

When I visit for the last time on a crisp afternoon the week before closure, it’s hectic. The phone is ringing constantly, the owners are harried and the door bursts open every couple of minutes with customers picking up final takeaways of their favourite dishes. Strewn across the floor are teapots, plates, industrial-sized pots – artifacts of an Auckland food institution. Some customers leave with a bundle of kitchen equipment.

As far as the hospitality industry goes in Auckland, 41 years is a long time to stick around. The restaurant, founded by two men who had migrated to New Zealand from Hong Kong in the 1970s, opened in 1981.

Ex-Hees Garden owner Wynsome Wong was married to one of the original owners, named Mr Tong. She worked at Hees Garden for 35 years, and was owner for 28 of them. Over the decades the restaurant was used as the location for commercials and made best-restaurant lists. It hosted celebrities and family events across generations. Elements of its unique decor were tinkered with and its menu gradually updated. Its colourful history is reflective of 40 years of change in New Zealand.

Wong is direct and decisive in her speech, in a way that’s typical among people who’ve worked in the restaurant industry for a long time. She speaks in quippy sentences and reiterates that she was hesitant to tell her story to a journalist. It was her children who convinced her it was important, both as a personal history and a reflection of the broader story of modern immigration in Aotearoa. “Our story is the legacy of the restaurant,” she says. But more broadly, “it’s an icon and it’s been a mirror to the social-economic changes in New Zealand for the last four decades”.

The early years

Wong came to Auckland from Hong Kong in 1978 under a tertiary scholarship offered by the New Zealand government. Back then, the population of New Zealand was relatively tiny, with just over three million people living here. “Sheep outnumbered people,” Wong says. They still do, but these days it’s around five sheep for every person, compared to the peak of 22 per person in 1982.

When you consider the wonderfully diverse range of Asian cultural exchanges and influences readily found in Auckland today, it’s hard to imagine that just over 40 years ago things looked vastly different.

Beyond the original early migration of Chinese and Indian migrants in the 19th century, there was actually very little ongoing immigration into New Zealand from Asia. For almost half a century, New Zealand’s strict and discriminatory immigration policies, explicitly geared toward excluding people from China, meant newcomers from Asia were rare.

In the 1970s, New Zealand’s relationship with Asia began to change. In 1973, the UK’s decision to join the European Economic Community led New Zealand to diversify its exports, as it couldn’t rely on continued trade with the UK. As well, growth of economies in South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong meant New Zealand began to see Asia as valuable a market for trade.

Still, it was “very hard to get a visa even to come and visit”, says Wong. In 1970, just 354 people from Asia migrated to New Zealand. When Wong first arrived, she recalls it being rare to meet other immigrants from Asia and correspondingly, New Zealand was relatively unknown back home.

Instead, “most Asian communities here were made up of people from the original generation of immigration”, she says. While studying psychology and sociology at the University of Auckland, Wong worked as a part-time waitress at a Chinese restaurant called J Garden, which is now gone.

After briefly returning to Hong Kong once she’d finished her studies, she realised she’d “fallen in love with New Zealand”. Wong came back, got married, had three children and worked at Hees Garden part time.

The unique decor, reminiscent of restaurants in Hong Kong in the 1950s and 1960s, had been painstakingly put together by the two original owners and Wong. “My father-in-law, who was a successful restaurateur in Hong Kong, imported all this interior decor stuff to us,” Wong says. They spent nine months building the restaurant, brick by brick, tile by tile.

When the restaurant first opened its doors, red lanterns hung from the ceiling and it mainly served non-Asian New Zealanders and early-generation Chinese New Zealanders. In the early days, it advertised on local radio with the rhyming tagline “If you haven’t dined at Hees, you haven’t dined Chinese”. That’s become somewhat of a motto among long-time customers, says Wong.

Back then, they were open for dinner and the food mainly catered to a non-Asian New Zealand palate. Think New Zealand-style Chinese takeaway staples like chop sui, chow mein and the hugely popular sweet and sour pork. All dishes that were “incomparable to today’s cooking standards”, she says. Even so, customers would queue out the front for a table before the restaurant opened at 5.30pm each day.

The doors open to Asia

Under David Lange’s Labour government, the Immigration Policy Review of 1986 marked a break in the previously existing policy that emphasised nationality and ethnic origin as the basis for admitting immigrants. That, along with the 1987 worldwide stock market crash, led to an active effort to entice Asian businesspeople into the country.

It was these changing immigration policies in the late 1980s, particularly the increase in people moving to Auckland from Taiwan and Hong Kong, that influenced Wong’s decision in 1992 to open Hees Garden for yum cha, a traditional Cantonese brunch. The two co-founders of the restaurant had left by then to start their own ventures and Wong had taken over. “I saw the need for modification, to serve those communities,” she says.

As well, the new policies meant she could bring in specialist chefs from overseas to fill trolleys with a vast array of dim sum. “Little delicacies, little dishes, which are not costly,” she says, “but if you eat a lot, that will be a different story”. Wong reckons that the majority of new Asian immigrants to Auckland in the 1980s and ’90s would have had their first New Zealand meal in her restaurant, having spotted the familiar-looking decor on their way from the airport to their new homes.

A new millennium

By the beginning of the 21st century New Zealand had become more closely linked to Asia than ever before. By 2002 Aotearoa had 17 Chinese-language newspapers and four radio stations. New Zealand became China’s first free-trade partner in 2008 under John Key’s National government. By the late 2000s New Zealand had established close political, cultural and economic relations with many other Asian nations.

“We had a big influx of new immigrants from China,” says Wong. Under Key’s government there was sustained emphasis on attracting wealthier immigrants. “All these rich people came in, to buy houses and spend money, put their family here and support their living,” she says.

The increase in Chinese migrants also correlated with the opening up of the tourist industry. “So we had huge numbers of tourists coming from all over the world, particularly from China,” she says. It wouldn’t be a rare sight to see 10 tour buses parked outside the restaurant back then. “That’s how busy we were.”

At the same time, because wealthier immigrants were arriving, larger-scale Chinese restaurants like Grand Harbour and Grand Park began to appear around Auckland. “We had more and more Chinese restaurants, bigger Chinese restaurants, more modern Chinese restaurants opening up,” she says. That made Hees Garden seem very small. To keep up, Wong (not without objections from some locals in the neighbourhood) made a significant expansion of the restaurant in the early 2000s by way of a new function room. “That was a major restaurant change to respond to the social change at that time.”

Importantly, she adds that many of these newer immigrants maintained their cultural identities and links with China. This meant adapting their menu to include more varied regional dishes from across China, particularly northern and Sichuan cuisine.

Controversy around shark fin soup in 2012 provided an “interesting episode” too. Environmentalists demanded Chinese restaurants around the country stop selling the delicacy. In response, “we took shark fin soup off our menu”, she says. “Hees Garden was the first one to respond to that call.”

“You answer the calls of society, what the society needs, what the community needs, and you have to be smart enough to answer that,” she says.

Celebrities, politicians and other prominent figures have stopped by for a feed at Hees Garden over the years. Ex-prime minister Mike Moore stands out. The Tongan king and his family were regular customers too. “And he loved our crayfish,” she says. Particularly memorable was Cliff Richard’s birthday party in 1990, which was held in the restaurant. “He finished the concert and the whole crew came over, there were about 40 or 50 of them, we had a great time…I had his signature on my uniform.”

Over her 40 years of connection to the restaurant, Wong has trained staff, helped bring their families to New Zealand, hosted weddings and christenings of children who grew up in the restaurant and made lifelong friends. “That’s a big achievement,” she says. Her three children, now grown up, all have very close ties to the restaurant. “They’re very grateful that they had that experience which helped them to become who they are today,” she says.

In the 2000s three new owners came onboard to help Wong run the restaurant. They went on to carry the torch after Wong retired in 2017. Since then Wong has been volunteering for St John, the Citizens Advice Bureau and Age Concern. Pre-pandemic, she’d do a yearly round trip to Singapore, Hong Kong and the UK to visit her children and siblings living overseas.

As we sit in the cafe directly across from the soon-to-be-closed restaurant, I tell Wong that my parents had their first date at her restaurant in the ’80s and it was the place where I first had yum cha as a child. Wong responds with a term she likes to use, “collective memories”, to describe that kind of shared history many Aucklanders have with the restaurant.

“You hear the story of Hees Garden, you hear an important chapter of New Zealand’s history,” she says.

Since the restaurant closed, Wong has received messages from all over from people curious to know whether there will be a Hees 2.0. Her answer? Undecided. “You never know, right? But I’m certain the legacy of this restaurant carries on.”