Summer reissue: A few years ago, deep into middle age, Britta Stabenow found solace in the world of gaming. Now she’s part of a passionate community: those who love, and collect, video games.

This post was originally published on 27 June, 2019.

I’ll always be a video game collector, that will never change. But the collecting community reached a really low point this year with the Poop Slinger affair. It held up a mirror to video game collectors worldwide, hungry for “rare” games, and asked: Have you sunk this low for a third-rate, ridiculous game that lacks any accredited reviews? This game literally slung poop in our faces and said, “There! You know you want it!”

The publishing and retailing of physical video games is tripwire territory these days and everything about Poop Slinger was scripted for an epic failure: an unknown US company run by a Russian who was unaware of the cultural significance of April 1st, a pitiful website store, a sales-or-bust deadline of one day. Not surprisingly, savvy game collectors assumed this was an elaborate April Fool’s joke, especially since the company name Limited Rare Games so openly mimicked that of established and successful outfit Limited Run Games. What had likely seemed a surefire way to set up a nice little cash cow turned into bankruptcy at the end of the day and creditors took control of the remaining (1,000 minimum Sony print run minus 84 sold copies) stock.

For the record, I did not purchase a copy, but I also certainly can’t afford to be smug. Some of my friends in the collecting community did secure a copy and all I can say is that it’s undoubtedly a solid investment, going by the prices on eBay. Poop Slinger (released digitally to no fanfare in 2018) now has the dubious honour of being the rarest physical game release (on PS4) ever. There are only 84 purchased copies known to exist out “in the wild”, making this the juiciest story on the Wild West frontier of that obscure hobby known as: collecting video games.

A collector needs to be like one of those first-edition book sellers. Remember those musty-smelling decrepit shops with old fogeys discussing ‘foxed’ pages and clipped dust jackets in-depth? That’s me. I’ve turned into one of those. A video game collecting boffin. Me, who didn’t know what a video game looked like until well into my later years.

How did it happen? Maybe there is some genetic code with the imprint ‘careful -> video gamer -> obsessive-compulsive candidate’?

As a kid, in post-war Germany, I was in that first generation who grew up with television, the new medium, widely believed by our parents to be responsible for the downfall of Western civilisation and the brain rot of their children. As luck would have it, my mother worshipped the TV set, and Lassie became my goddess and the Ponderosa ranch our home. I devoured everything the German TV channel (yes, kids – one channel!) scraped together to fill its programming schedule: Scandinavian Astrid Lindgren adaptations and of course the Moomins, sombre Russian movies, effervescent Czech children’s TV, Italian neorealism, German stage plays, and the colossus towering above all: American entertainment. My generation absorbed the code of this new, screen-based story-telling and it transformed the way we saw the world.

I went on to study social sciences at uni and was notorious as a senior student who dared to keep a tiny black-and-white TV set with rabbit ears in her digs. How bourgeois! Books, movies and TV remained the staple I fed my imagination on, throughout my years in various jobs, setting up home in Britain, then settling in New Zealand. I was very text-focused back then, in the 1990s, with a chance opportunity leading me to a fiction writing course with Owen Marshall.

Maybe that’s why games passed me by? I was not in the target age group for video games, and the only time I saw one, on an old Atari computer that had green pixels hopping across the screen, it didn’t connect with my thirst for colourful, exciting adventure stories.

Computers could not be avoided; they were the new frontier and, yet again, by serendipitous chance, I stumbled into the very first NZ course about the internet, also conducted via the internet: Internet Alive! Something clicked in my brain circuits and I became obsessed with learning and working with these fabulous machines. I hope you noticed that “o” word – it looked like the rail tracks of my life were finally converging.

But life doesn’t quite work like that: methodically, logically shunting you towards the pre-booked station. I was perfectly content with my computer work, mostly web design and server admin, sustained by literary and filmic fodder. The great joy of my life were my dogs.

One day tragedy decided to extinguish the one creature closer to me than most humans had ever been. The cruelty of grief stole from me the two great pillars in my life: books and moving pictures. Decades of finding solace, laughter and thoughts worth holding vanished because my synapses would not allow me to focus on a story for more than a few minutes before autonomically fastening onto a never-ending replay of how darkness swallowed my world.

Video games did eventually manage to do what nothing else could: beat back the darkness. But it was hardly a deliberate decision on my part. Clearing out old rubbish, I found a brand-new Playstation 3 I had won in some contest, stowed under a bed. Slowly, like a crash victim learning to walk and talk again, I began to decipher the language – the code, if you will – of video games. This new medium demanded my absolute attention, a new kind of literacy: both technical know-how and flights of imagination needed to work together to create something, on the screen, that had my imprint on it. Finally, my synapses realigned, and I embarked on what would become an all-consuming project: traversing the length and breadth of video games, trying to do in a few years what most gamers spent 20 years and more experiencing.

Maybe obsession is just another word for cramming as much as you can of what you love into this life?

The PS3 proved a wonderland of so many different genres and styles of games. I explored them all, avidly, but quickly found my special niche within role-playing games (RPGs). A gamer friend, who took me under his wing in the early days, suggested the Atelier series, a long-running Japanese franchise that melded crafting (who doesn’t love alchemy?), exploration, monster combat and social simulation into a unique hybrid.

In my first Atelier game I was instantly absorbed by the story of young alchemist Ayesha searching for a sign of her long-lost younger sister, Nio. The game is beautiful, touching, sad and exhilarating, and released a wellspring of emotions about loss that I realised I hadn’t really managed to travel through. By the end of the game, I emerged on the other side and knew that video games are a powerful aid in healing.

All traditional RPGs are essentially rites-of-passage: a young person sets out on an adventure, faces adversity, succeeds with the help of others, and in the process learns about him/herself and the world. In short: it’s all about growing up.

Playing an RPG means you can relive that powerful experience; it never grows old, we are forever young adults on the brink of great adventure and discovery. It sounds like escapism, and of course it is – what form of entertainment isn’t? – but it is also one of the great gifts video games have given me. In a corner of my heart I will always be that teenager, looking for that next adventure, never taking No for an answer.

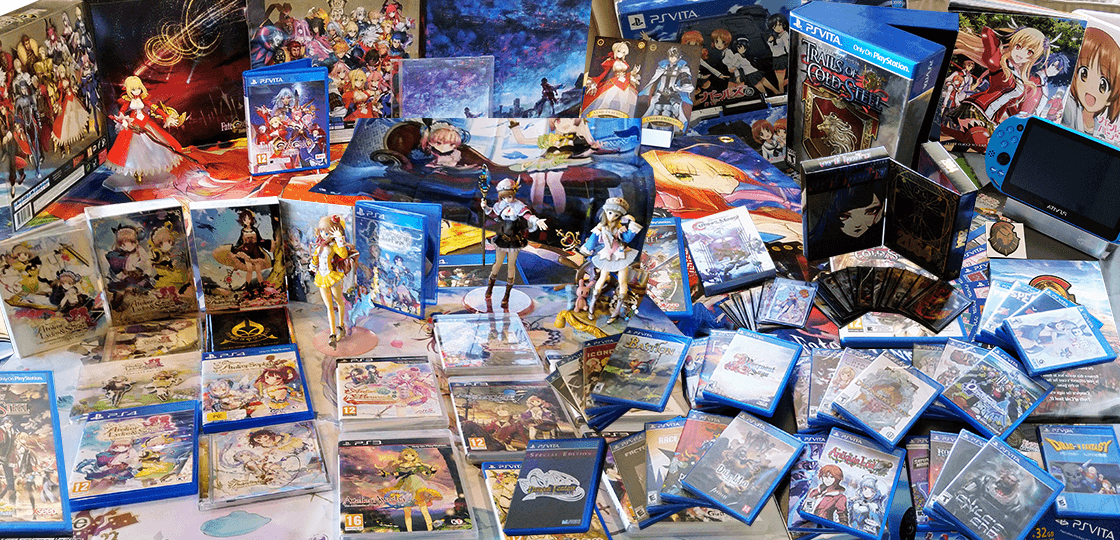

In those days – with internet connections still slow – I bought most of my PS3 games on disc; that way I discovered the joys of gradually accumulating a library, rounded out with Atelier artbooks, decorative cloths and figurines. In 2013 I purchased a Playstation Vita, and that sealed my fate as a dedicated handheld gamer and collector. I soon realised the pitfalls of digital distribution for a poorly supported console and shifted to buying Vita games in their cartridge format wherever possible.

In 2015, everything changed when Limited Run Games was founded and offered its first release: PS Vita game Breach & Clear, 1,500 copies, no repeat run ever. They sold out within two hours and a legend was born. And this also happens to be the point where my rather casual habit of buying physical games and the odd limited edition turned into… a bit of an obsession.

The two founders of Limited Run Games are game collectors themselves: preservers and archivists of a rich culture threatened by the ever-hungry maw of corporate sell-it-and-forget-it practices. We have libraries for books, museums and galleries for art, but no concerted effort to collect and preserve the physical history of a modern art form many think will soon overtake (or symbiotically merge with) movies.

So what does this lofty ideal have to do with that unsuccessful portable console that Sony sidelined as early as 2014? The answer is: a business model.

The Vita happened to have a very high “attach rate” – that’s industry-speak for a high ratio of game titles sold per console unit. In one sense you could say that the very low sales for the Vita console benefited this ratio, for it meant that only hardcore, devoted handhelders flocked to the gaming stepchild and spent proportionally large on game software.

LRG put two and two together when, from 2014 onwards, they saw the output of physical Vita titles shrinking faster than you could say ‘Sony shareholders conference’, and compared that with what can only be described as a stubborn, fanatical player base. I counted myself among those Vita fanatics and joined their Twitter haven, called #VitaIsland, to better follow the announcements of “limited runs” and network with other Vita nuts and indie developers who quickly found a home on Sony’s abandoned little platform.

Ah, those were the golden days. The Vita Lounge’s TVL print Magazine was still going strong, publishers in the West were still prepared to invest in localisations of Japanese Vita games; and then there were those feverishly anticipated ‘events’ – a new game release by Limited Run Games! The grand project of giving languishing digital titles a physical home struck a chord with gamers, and other start-ups joined the bandwagon; Strictly Limited Games, Super Rare Games, Red Art Games, and more. The pace accelerated, the numbers of would-be collectors skyrocketed, and the scalpers moved in.

I managed to keep up my spirits throughout 2018, turning to what we call “import games” when English-language versions began to dry up. The number of Japanese Vita games is mind-blowing. I had to face facts: there was no way I could buy and collect every Vita game out there! As we reached the final stretch of PS Vita cartridge and console production at Sony (the death certificate is dated March 2019), LRG ramped up their final contracts with developers and added new console platforms to their portfolio.

Every Friday (Eastern Time, US, Saturday morning for us) the company pushed out two batches (eight hours apart) of their limited runs, often multiple games, and the community stress levels were rising steadily. That’s right: collectors do get stressed. They will actually go off their collecting rocker on social media and the fallout always highlights the love/hate relationship they have with LRG’s business model.

As I slouched into 2019, the toll was mounting. The long hours scanning listings on eBay, four regional Amazons and other Asian trading places to track down over-priced copies of games that had eluded me at release wore down the thrill of the collecting hunt from pleasure to chore. Worse, weekends with Limited Run Games timed sales caused panic attacks and grumpiness. We prepared like a Black Ops mission. Alarms were set for 2 or 3 a.m. (if I needed to catch the first batch), teapots ready to keep me awake, my phone set up for the correct LRG product pages with account and payment details all checked. I would hunch in front of the router, watching the timer tick down on the website, my finger poised to refresh the page and then do a lightning stab on the Add to Cart button.

Of course things often went wrong. The server crashed under the load, or the shopping cart froze. Then a few hours sleep until the second batch; rinse and repeat. I lost most of my Saturdays, then, in a haze of tiredness, anger at another failure and rage at the professional scalpers who set up multiple fake accounts and use scripted bots to grab those few precious copies. Afterwards, there were the endless postmortems on Twitter and in the private group of collectors I liaise with online.

That’s the other, unexpected, side of collecting. You think we’d all be at each others’ throats, competing for limited resources. But that’s not my experience. I made so many online friends through this collecting craze – there, I said it! – and it’s the one aspect that helped keep me sane. It’s an unspoken, unwritten Collectors’ Code, in a way. We support each other in the group: for limited runs we know are going to be cut-throat difficult we try to organise in advance so that there will be spare copies for those of us at the wrong end of a timezone or a misbehaving server. We offer for trade what we can share, rather than trying to squeeze maximum dollar on eBay.

I feel like I’ve been through the crucible of collecting madness – call it addiction or obsession, if you like – and finally recognise it as a chimera, attainable only with unlimited time and funds. I’ll always be a game collector boffin, it’s deep down a part of me now. But these days I don’t need to chase every desirable game edition: I can look at my collection and simply enjoy what I have.

After all, it’s the strong emotional and often nostalgic ties to games that hold a special meaning for me. That’s what collecting really should be all about.