A new photo series created by the government’s cybersecurity agency wants to make people more wary of scamming. It got Shanti Mathias thinking about how limited we are in illustrating – and imagining – the systems that produce scams.

When the crime happens, there’s no broken glass, no loud noises, no neighbourhoods cordoned off. There’s just flatness: a voice on the telephone, black letters on a screen, tapping keys, replying, trusting – until it is suddenly clear that what you thought you were doing wasn’t happening at all.

It’s hard to write about scams, even though they happen all the time; even though thousands of people are targeted each month. New Zealand loses about $20m a year to scams, and that’s just what gets reported. It’s difficult to imagine the magnitude of the small losses, or the money that is able to be recovered, or the thousands of missed calls and dubious Facebook messages and other near misses that dissolve, back into the ether of ones and zeroes.

Difficult to imagine: yes. Difficult to image, too, and that’s part of the problem. I’ve written several stories about scams this year, and finding imagery that fits the tone of the stories is challenging. There are endless stock images of people, often older people, looking angry or confused at their laptop, surrounded by credit cards. Then there are the scammers themselves: lit up by rows of binary blue digits, always wearing hoodies, faces shadowed.

These images don’t convey the banal malevolence of scams. They’re not a threat because we are confused about technology, while scammers are experts in manipulating the internet. Scams are a threat because we have to engage with technology. Our society requires us to trust banks and authenticating text messages, trust RealMe, trust the websites we give our address and phone number and credit card details to when we shop. Pictures of people perplexed by the internet fail to illuminate the everywhere-ness of technology, part of all we do.

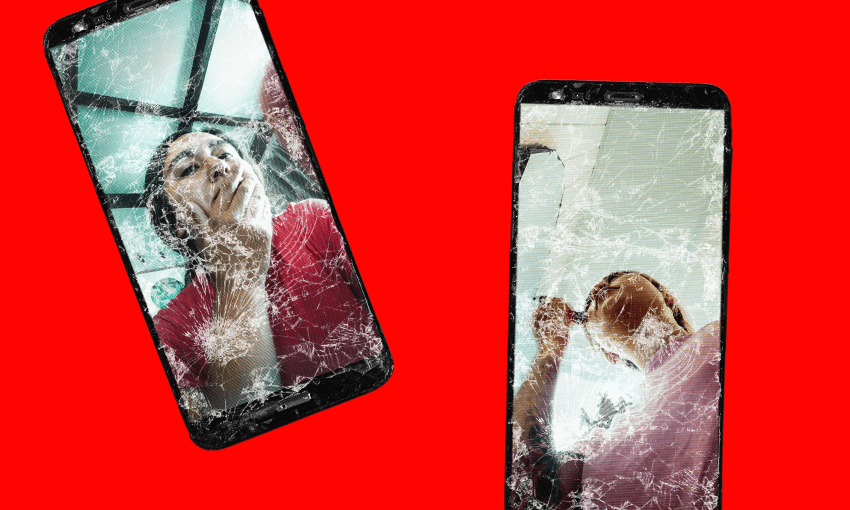

Cert NZ, the government’s cyber security agency, clearly struggles with finding imagery that can help people care about scams, too. A few days ago, I trotted along to an event they were hosting at central Auckland creative venue The Tuesday Club. Scams like an art exhibit: big photos on the wall and little labels. A library of scams: romance and impersonation scams, social media traps and investment scams, job scams and unauthorised access scams. The photos were taken of real scam victims, through webcams on phones and computers. The images were then treated to look pixelated and blurred, uncomfortable. It’s called EXPOSED.

The photos are a reminder of all the ways our devices see us: present as we do press ups in time with the woman on YouTube, call our friends, pick our nose, wonder when the work day will be over. And scams come from that place of inattention and ubiquity. My phone is my key to my bank account, my family group chat, my archive of good days with good friends – and yet simultaneously, it is the same place where I am in danger from 15 texts telling me I need to pay for a toll road, from message requests accompanied by ersatz pictures of beautiful women.

“Everyone is a target, every demographic – if you have an email address, a cellphone, social media. One moment of distraction is enough,” says Sam Leggett, Cert NZ’s senior threat analyst. “The imagery is highlighting this idea that [being scammed] can happen at any time… it’s a powerful way to understand how exposed your information might be.”

Cert NZ has lots of advice for avoiding scams, but this threat happens in the privacy of our own devices – what stock images would make it more visible? “One that comes to mind is tables of lists of passwords, the backend of a phishing campaign – people don’t realise that websites all around the world have data breaches including information like email and passwords,” Leggett says. Ah, there’s the rub – often, there’s nothing you can do about being targeted by scams, because the information is gone already.

Another image idea, this one conceptual: “Someone is knocking at your house, and they’re wearing a mask, so they look exactly like someone you know. The person in the mask asks for the keys to your house – maybe they’re your landlord, you let them in to fix something. And then a hacker is inside, now they have your logins, they can access your stuff.”

That’s figuratively exactly what happened to William Chen. He used to be an art director, managing photo shoots for magazines – so he knows that while the image of himself used in Cert NZ’s exhibition, distracted and eating breakfast, isn’t exactly flattering, that’s not the point. “I’ve put others through it, so it’s my turn,” he says. If a photo of him makes it less likely that other people will fall for a scam, he’s willing to be public with it.

A few years ago, Chen was visiting family in Malaysia when he got a message from a Filipino friend, saying that he had been mugged in Manila and lost his passport and needed money urgently. It was an impersonation scam. “All the tell-tale signs were there,” Chen says ruefully. The scammer wouldn’t answer detailed questions, for example, and wanted money paid through Western Union. Over a period of only a few hours, Chen received message after message with harrowing descriptions of his friend’s misery, and the urgency of help; he eventually went to the local Western Union to send money as instructed, then told his sister about the situation. She immediately told him he’d been scammed.

“I wasn’t sharp enough,” he says now. He feels guilty about it – and still paranoid that messages he receives on social media might not be legitimate. “It’s good that [Cert NZ] is raising awareness, but I don’t think the government can do much about scams – it all boils down to personal responsibility.”

Maybe Chen is right, but it’s not that big institutions are doing nothing about scams. Take the man in the news recently for losing $400,000 to an investment scam. He was repeatedly called by his bank, to warn him that it was a scam. The outgoing government announced a new anti-scam team a few weeks before the election; since the issue isn’t highly politicised (or on the ambitious 100 day hit list), the new government hopefully will continue to support this initiative. Banks, especially, will keep putting safety measures in place; an obvious one is payee verification on transfers, so it’s clear when you’re not paying who you think you are.

Pictures of scamming can show victims as human beings: distracted and vulnerable, their information ripe for the picking. The Cert NZ photo series goes some way towards making these images more compassionate, more diverse, less victim-blaming. There’s a deeply complex, psychological element to being scammed – the urge to believe that something is true, that someone is trustworthy – but in the imagery of scams and the focus on victims, we fail to imagine who is on the other side of the phone.

Taking photos of victims is obvious, if important. It’s so much harder to picture the people carrying out the scams, and the systems that enable them. For instance, how do you photograph the thousands of forms with your address or birthday or phone number that you fill out every time you make a useful account on the internet? How do you visualise the profits of a company that didn’t hire an extra data engineer and thereby releases your information and thousands of others to potential hackers and scammers via a data breach?

There’s a subgenre of YouTube videos devoted to unmasking scammers through elaborate pranks. This is a reminder that scamming is an enormous global industry, employing thousands of workers in places where the law doesn’t want to look very hard for crimes that happen on the internet.

In some parts of the world, there are many more underemployed educated young people than there are well-paying jobs, which can make carrying out scams a viable, if not appealing, option. That’s a product of global inequality, but it’s difficult to draw a picture of. There aren’t compelling photos of the dreary office parks in the corners of global cities – Abuja, Kolkata, Bandung, Hyderabad, São Paulo, Budapest, Karachi – and the workers inside them, carrying out the dull labour of digital deceit.

I don’t say this to suggest that the work of scamming is good work, that it is somehow part of global wealth redistribution. There’s no transparency to these payments; the money is unlikely to go to those who need it most, and the losses hurt people with the least financial stability. But trying to imagine what scamming people might look like from every angle is essential if we don’t want these to keep happening. While artificial intelligence improves, there’s every likelihood that the scams will just get more convincing.

Maybe some form of scamming will always exist, but much of the damage is preventable. The solutions involve individual wariness, as the CERT photos show. But responding to scamming also requires the government to treat it with the urgency it requires, social media companies to cooperate and private institutions to improve their processes. Maybe if all of that happens, scamming will be less profitable, and it won’t be a job for people in countries whose governments are incentivised to look the other way. Maybe. It’s hard to picture.