In the effort to stand out, brands often post photos that look extremely similar to everyone else’s. For IRL, Shanti Mathias tries to find out why.

There is a place tidier than reality, and it’s millennial pink. The colour is nearly perfectly epitomised by the branding and packaging of Monday Haircare, a shampoo brand founded in New Zealand by the partner of a billionaire. On Instagram, the bottles are square and artfully arranged in a flatlay. I look at the images and imagine having long and bouncy hair. At the supermarket, in an aisle of bottles with cluttered logos, my fingers twitch towards Monday products, pleasing in their plainness; distinct.

This is exactly what the branding is supposed to be doing, says Jaimee Lupton, cofounder of Monday Haircare. “I was used to seeing [shampoo bottles that] were all quite busy and “shouted” at you, whereas I wanted to create something that whispered,” she says. That minimal aesthetic translates well online. Monday’s Instagram page is determinedly pale pink, following the form of the bottles: clean, curated, and appealing.

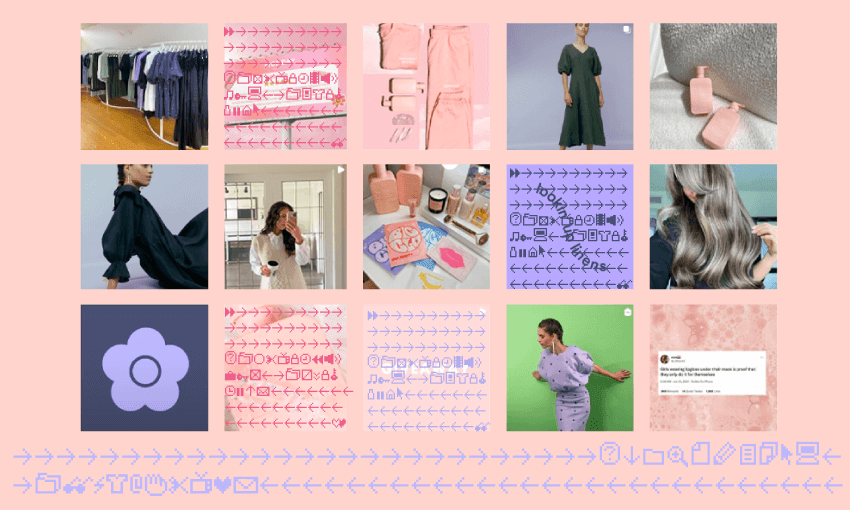

But it’s not just Monday. On Instagram, minimalistic yet colourful photography is everywhere. These images are being used to sell products, as well as to offer a tantalising glimpse of an idealised lifestyle. But what is an Instagram aesthetic, and where did the “minimal Millennial marketing” aesthetic come from?

The look of these posts is firstly practical: Alice Isles, co-founder of hej hej, an upmarket clothing label based in Auckland, says that their plain pastel backgrounds and clear, natural lighting allow the “clothing to speak for itself”. These characteristics of hej hej’s Instagram images share some DNA with Monday’s imagery and similar brands’ Instagram’s, too, like Kowtow, Marle, and twenty seven names.

When posting on Instagram, a brand wants those who see their pictures to purchase their products. To achieve this, having a distinct imagery style is useful, so that someone who sees their posts can recognise it as belonging to that brand even before seeing the handle. “Brands [often] have an emphasis on colour palette and many companies use presets or filters, [or] flatlays to create still lifes and products, to be in line with that Instagram aesthetic,” says Phoebe Fletcher, a lecturer in digital marketing at Massey University.

View this post on Instagram

Creating a distinct look helps explain why an individual brand might develop a recognisable flavour of imagery, but why do many companies promote their products with such similar photographs?

I suggest to Barbara Garrie, a senior lecturer in art history at the University of Canterbury, that the recognisability of Instagram marketing imagery is analogous to how similar styles develop within art movements. She agrees, with some caveats. In the study of art, aesthetics are a way to understand how artists use visual imagery to respond to the society they’re part of, a “visual vocabulary” of images that communicate or examine particular ideas. She notes that, just as there are distinct styles of art in the Cubist movement or in Impressionist painting, visual tropes appear on Instagram, too.

View this post on Instagram

The difference is one of scale: Instagram has over a billion users, with thousands of different styles of imagery developing concurrently, and the “acceleration of images” means that thousands of pictures are produced by thousands of people (and companies) trying to both look like each other and stand out. Given the sheer volume of Instagram imagery, many brands gravitate towards the same styles.

Just as artists are limited by the medium they choose – a painting is something very different to a sculpture – the look of posts on Instagram is also constrained by the features of the app. Notably, brands encounter many of the same restrictions as individual users; other than being able to flog their wares in the Instagram Shopping tab or sometimes being verified, brand accounts are on an even footing with the people they’re promoting their products to.

“What is interesting about Instagram is that that platform codifies a certain aesthetic, through things like filters [and] that square frame,” says Garrie. “These features are normalised so we understand something as having an Instagram ‘look’.”

This is distinct from how brands worked in the past: the photography on a billboard advertising a new shampoo was obviously differentiated from somebody mailing the developed photos of their Fiji holiday to a friend. On Instagram, the “visual vocabulary” of brands Garrie refers to is surrounded by images of people you know personally and celebrities you’re interested in, creating a context collapse. Given this, brands face a difficult balance in creating imagery that both fits in with the other images on a user’s feed and clearly promotes their products.

This is a tension that Maya Brown, managing director of Content & Co, a social media agency based in Auckland, is intimately familiar with. She’s quick to point out that there’s a diversity of approaches to visual imagery between different brands, but agrees that companies try to create a “unique and cohesive look of [their] feeds over time”. She says these artful compositions have to be balanced with user-generated content, like a picture of a real customer wearing a brand’s clothing, to “create a mode of authenticity” – and blend in with the pictures of real people that an Instagram user will also be seeing.

The look of a promotional Instagram image also has to clearly signal to the demographic the brand is targeting. “Each brand designs their content to appeal to their audience,” says Brown. Aiming at the right demographic is crucial. “I’d consider our demographic, which is Gen Z and young Millennials primarily, to be really switched on and stylish, so we naturally want to give them something they relate to and can see themselves and their taste reflected in,” says Lupton, of Monday Haircare. By looking alike, similar brands appeal to the same audiences, like the kinship between hej hej and Kowtow pictures on Instagram, a way for an account to say “We are for people like you.”

As a twenty-something female who had to peruse Instagram extensively for this article, I can confirm that this works. Scrolling through a blur of floaty-coloured clothing hanging on the bodies of elegant models who look like (very beautiful) people I might know, I can’t help but desire what they’re selling. Beside this, though, is an acute irony: in the quest to look unique, many brand Instagrams targeting my demographic look nearly exactly the same.

It’s notable that many of the companies who use this minimal Millennial aesthetic are also selling aesthetics, invariably to women: clothing, skincare, make-up, things to make you look good, perhaps even in the photos you post to your own Instagram account. Is there anything substantial beneath the images?

“We try to be authentic in everything we do,” says Isles of hej hej, pointing out that their collections are made from natural fibres. While uniformly beautiful, hej hej models are a range of shapes and sizes, which Isles hopes “form[s] friendship through imagery” and makes those who see the pictures feel included.

Having “brand values” like the vaguely defined ideals of sustainability, authenticity, and inclusivity on your feed is important when marketing to millennials and Gen Z, says Brown. Fletcher, the marketing academic, agrees: “People want [Instagram] to be a reflection of how they feel, so it becomes a way of showing brand values.” Gesturing towards these “brand values” also contributes to the similitude of Instagram posts.

Visually, this is often demonstrated by natural elements, like plants or the sea, in branded Instagram posts, and having a range of models, while captions may reference the environmental credibility of the product, or best practices throughout the supply chain.

View this post on Instagram

The social media experts planning and posting commercial Instagram images hope that breezy, immaculate framing looks just as effortless as posts from influencers or ordinary accounts. That effortlessness requires a great deal of work to create and approve, says Fletcher: “You want to think about how you’re positioned and how someone in that demographic might perceive your brand and … your value proposition [compared to] your competitors.” Brands might draw on market research and “clickthrough conversion” (ie, how many people buy from your link in bio), as well as trends and influencers, to decide what to post. There’s nothing organic about these images.

The technology and trends of Instagram may create a distinct style of marketing images aimed at a particular demographic, but does this mode have any staying power? Even marketing professionals, who work all day with tempestuous algorithms and capricious consumers, aren’t sure. Garrie, the art history lecturer, suggests there might be another analogy in the way that the art canon is formed. There are processes – based on whim and money and power and coincidence and national events – which determine which works of art are remembered. Perhaps the Instagram algorithm functions similarly: it’s a vacillating force that decides who sees a picture, and what it might mean.

View this post on Instagram

“It tells us something about the values that were important at the time and the kinds of ideologies people held,” she says. “[With the algorithm] some things get visibility and some things get forgotten.”

Just like individuals, companies of all types and sizes are working with one of the world’s biggest companies which is interested in its own profit, not theirs. “The internet is [now] this banal, common place in our everyday life,” says Garrie. It’s filled with friends – and companies trying to look like friends – promoting their versions of reality. These images are a stylised aesthetic appeal, asking audiences to pay for how things look. Whether the images endure past the flick of a finger across a touch screen remains to be seen.