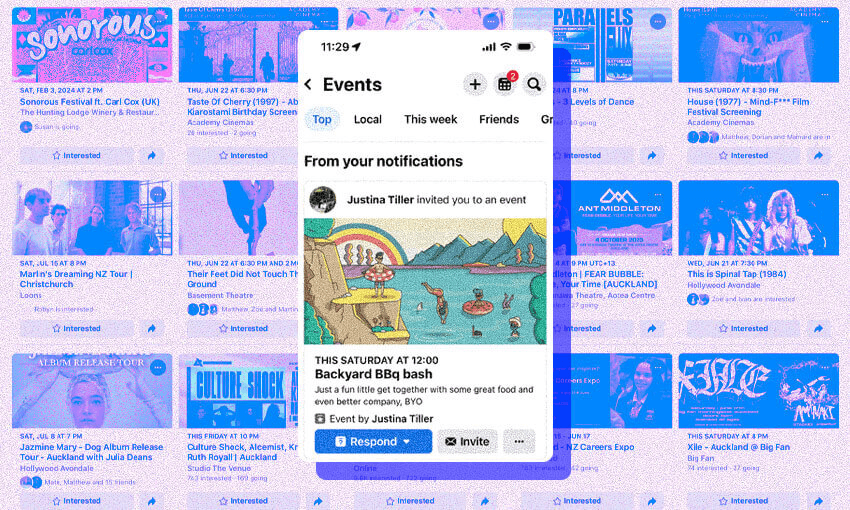

In the second part of a series about what keeps us logging into Facebook, Shanti Mathias explores the staying power of Facebook Events.

When I was at university, I felt compelled to log into Facebook about once a week, as well as messaging people all day on Facebook’s Messenger app. When I logged in, I always had about 10 notifications: half friends and siblings tagging me in memes, half invites to events. Twenty-firsts, flat parties, poetry readings – the main way I heard about these was on Facebook.

It was a useful feature: if you clicked “interested” or “going” to an event, you’d then get a reminder when it was actually coming up. You could see which friends (or enemies) had said they’d be there – a particularly handy feature if you wanted to “run into” a crush, or avoid an ex. If you made a new friend at the party, you could look at the event afterwards and find their name, send a friend request or message them. The frequent invites didn’t make me feel popular; it seemed to be how everyone heard about events.

I remember looking at my “events coming up” tab one weekend to see three events on both Friday and Saturday night, which I rushed chaotically between, swiftly changing out of a Snow White costume and into a 21st dress, able to find the location – and suss the vibe – through the tenor of posts on Facebook.

These days, I log into Facebook perhaps once a fortnight, often for journalistic purposes. The invitations are fewer; I can count the number of events I’ve been invited to on Facebook this year on one hand. When I scroll the newsfeed, I occasionally find events that interest me, but I can’t tell if they appear because friends might be going or because the promoter has paid for it to be advertised to someone in my demographic. Just as often, I hear about “things that are happening” in texts or emails or posters or even (gasp) in person.

This might be a wider story about how social lives change after university, the mass migration of young people to new platforms, or about the demise of flat parties as people’s housing and income situations change in their 20s (are they replaced by dinner parties? Do people start going to bars instead?). But it’s also a story about Facebook Events – a surprisingly durable feature of Meta’s nearly ubiquitous social media behemoth, even in 2023 – and what it’s good for.

“I use Facebook to promote the majority of my events,” says Amy Thurst, a Wellington-based drag performer and producer, who has created dozens of events over the last five years. “I don’t think anything can replace Facebook at the moment.” No other widely used social media platform in New Zealand has an events feature as fleshed out as Facebook’s, although it is possible to create event reminders on Instagram.

Sometimes, Amy’s events seem to gather steam naturally; people tagging each other in the comments, clicking “going”, buying tickets, telling their friends about it. “I did one event without any promotion and 4,000 people were interested in it,” they tell me. These days, Amy feels like they have to spend more money to get the word out, as much as $300 for a big event – a rough business for an operation of slim margins. The Facebook ad set-up is useful, because there are ways to target people who live in certain areas or have said they were interested in drag shows before, but it feels increasingly like a “pay-to-play” system.

Amy has paid for physical posters, too, and there are always ticket sales to indicate how many people are actually going to show up: paying cold hard cash to go to an event is always going to be a more reliable indicator of who will really show up than a list of people who have spent a millisecond clicking “interested”.

There are, of course, alternatives to Facebook Events, although they don’t necessarily have the network effect of Facebook’s thousands of users. Amy often lists their events on local stalwart Eventfinda. They say that although it’s not as seamless as Facebook, it is a good way to help people discover events as well as being an option for selling tickets. (As with Facebook Marketplace, Events is mainly monetised through advertising; it is possible to sell tickets on Facebook, but only by creating external events on a platform like Eventbrite or Eventfinda.)

While it’s usually used for public events, Eventfinda does allow unlisted events, which won’t be picked up by search engines, although it can’t be used for personal events like parties. “During Covid-19 restrictions we helped a person keep track of their attendees for a private party so they didn’t go over the limits,” says Anna Magdalinos, head of ticketing at Eventfinda.

To Magdalinos, Eventfinda’s differentiation from social media is an asset. “Unlike social media platforms, we’ve created Eventfinda specifically for the events industry… Although adding events to Facebook gives you an extra channel and reach, our event listings are what will show up in Google and where people can easily find and buy tickets.”

Amy says that the queer-specific nature of the events they run means that Facebook has at times not allowed them to post about an event without removing particular words or phrases. “You have to asterisk out a word if the bots that read your ad think it’s a problem,” they say. They appreciate that Facebook is a way to find people who are enthusiastic about drag events. But at the same time, Amy says, there’s a discomfort in depending on a platform that also hosts anti-trans hate and homophobia. Facebook is a place to find cool drag events; it’s also home to individuals calling for drag bans, with sometimes minimal moderation.

Platforms like Eventfinda can have more of a human touch. Magdalinos says the platform focuses on connecting directly with users, including via a newsletter with more than 500,000 subscribers across Aotearoa. I’ve found myself on multiple occasions browsing Eventfinda to see if anything is going on in my area – it fulfils that role well.

But despite Meta not making any major changes to the feature for the past five years, the sheer utility of Events seems to keep it lumbering. While perusing some Facebook group mango drama last week, a notification popped up: I had been invited to a friend’s leaving drinks. I clicked going, then marvelled at the alchemy of it, how checking a box on my screen became bodies in a room, movement, conversation.