In the garden city, you don’t grab a kebab, you smash a souvlaki. James Dann sets off on his own Greek odyssey to find out why.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a drunk man in possession of a few coins must be in want of a kebab. Ripping into one at two in the morning is as key to a night out as “town shoes” and queueing for 45 minutes for no apparent reason. Given the ubiquity of kebab stores in the centre of Auckland, Wellington and Dunedin, how did souvlaki become Christchurch’s flat-bread-with-hot-meat meal of choice?

Growing up in Christchurch, I always thought souvlaki and kebab were synonymous. On a family holiday in Greece, my brother and I were both amped to eat souvlaki every day, only to be slightly disappointed to discover that the mainland version of the dish is served open on a plate, rather than rolled in a pita.

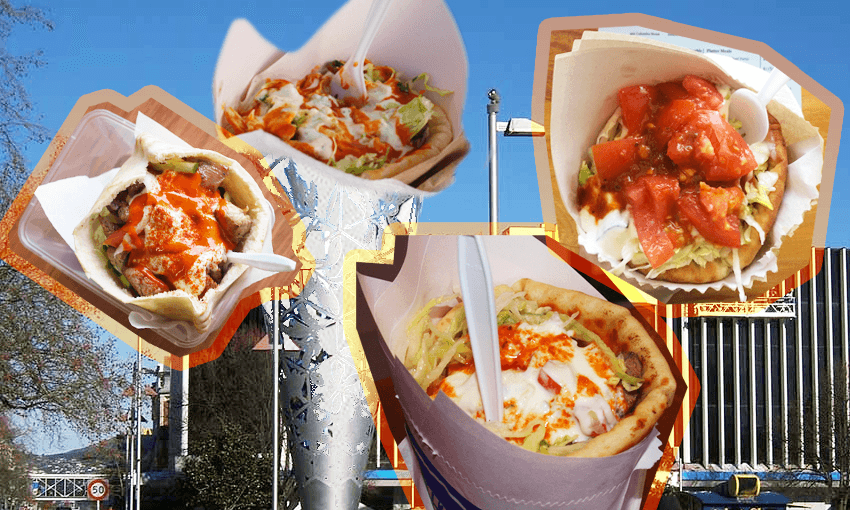

So here’s a brief primer on the variations. The word means “skewer”, denoting the method by which the meat is cooked; pieces of meat are threaded onto a spike and then cooked over coals. In what we generally refer to as a “souvlaki”, the pieces of meat are then placed on a pita, along with lettuce, tomato, and tzatziki, before the pita is rolled into a cone, a fork is chucked in the top, and the souv is delivered from the caravan to an excited recipient.

Kebab shops here and across most of the Western world usually sell doner kebabs. The main difference is that the meat is shaved off that big rotating spike you see in the window, rather than being cooked as cubes. With the meat on the centre of a flat bread, and the addition of salads, it then gets wrapped up entirely in tin foil, which you can then pick out of your teeth the next day.

To make matters more confusing, we’ve got gyros. Greek in origin, these have pita and salad like a souvlaki, with the difference being that the meat comes from a rotating cone like a doner kebab. The name, gyros, comes from the Greek for circle. Gyros are the default meat-and-flat-bread dish in many parts of the world, including North America and, oddly enough, Adelaide, where the name has morphed into the Aussie “yiros”. There are so many yiros shops in the South Australian capital that the annual “best of” list has to whittle it down to just 25. So how is it that Christchurch chose souvlaki over kebabs, gyros, or yiros?

The dish was clearly popularised by Greek immigrants, but that doesn’t really explain why it happened in Christchurch. Wellington has the strongest Greek community in the country, with some estimates putting almost two thirds of New Zealand’s Greek population in the capital. Despite this density, Wellington’s Greek community has had more impact on soccer (Dennis Katsanos, Kosta Barbarouses, Leo Bertos, and, er, Terry Serepisos) than souvlaki.

Though there are fewer of them, Christchurch’s Greeks have played an important role in the city’s food story. Theo’s Fish Shop has been selling fish, and fish and chips, from its Riccarton Road spot since 1950. Also from Cyprus and also involved with fish, Kypros Kotzikas turned United Fisheries into a one of the biggest seafood companies in the country. He celebrated his success in business and his origins by building an amazing homage to Greek temples as his company’s HQ. Phenomenally, this building also doubles as the office of the New Zealand consulate to the Republic of Cyprus. Another food company with Cypriot origins (there’s a theme here) is Giannis, the largest flat-bread manufacturer in the country. These guys supply almost all of the pitas that are such a vital element in the souvlaki.

Costa’s Souvlaki Bar was the first in the country when it opened up in Armagh St in May of 1984. It was there until the February 2011 quake, after which Costa’s moved out to Papanui. Co-owner Ana Lakakis’ parents set up the original souvlaki bar, and she says that the offering has changed over the 30 years that they’ve been in business: “Our souvs were much more traditional back then and they’ve since evolved to suit the Kiwi palate. They used to be rolled up in a much smaller pita bread and the options were either beef or lamb, with tomatoes, onions and tzatziki sauce — that’s it. We temporarily put hot chips in there too, the way they do it in Greece, but that didn’t take off at all. We have since introduced lettuce, other meats and falafel and other sauces.”

By the end of 1985, there was a second souvlaki in the CBD — Dimitris. Now running in two locations, it’s the Riccarton store I head to to find out a bit more about the man behind it all. Dimitris Merentitis (also known as Dimitri) arrived here from Greece in 1984, and after almost a year in Invercargill, he made his way up to Christchurch. Initially operating only at the weekend from a table in the Arts Centre food alley, by 1987 his caravan was also selling souvlaki in the square, Monday to Friday. He found a permanent home in the early 90s, just off the corner of Colombo and Hereford Streets. This was the location where Merentitis went from Greek Man to Greek Myth. As the legend spread, a souvlaki from Dimitris became a must-do on many people’s trips to Christchurch. Merentitis lists an array of people who he’s served, including multiple All Black captains and coaches, Danyon Loader, Jason Gunn, Gandalf, Bill Clinton’s diplomatic protection squad. In the 90s, the Black Caps would request that Merentitis bring his caravan to Lancaster Park when they were playing in the city.

That he’s served all these people — and that they’ve chosen to frequent his store — is a testament to how hard he works. Merentitis would be forgiven if, after more than 30 years, he’d moved behind a desk and let the next generation take over the small empire he’s built, but when I come in to meet him, he’s just stepped out from behind the grill. In addition to the bricks and mortar shop in Riccarton Road, he has a caravan in Cashel Mall. The return of the caravan to the Re:Start mall in 2013 was seen as a major boost in the rebuild of the central city, and despite the rest of the temporary mall being removed, the caravan still does a roaring trade at lunchtime.

For any given week, Merentitis will run one of the stores, while his brother Nick is in charge of the other, and then they’ll swap the next week. Merentitis is keen to stress his credentials, not only as a Greek but as a chef as well. While the core of a souvlaki is simple — meat, lettuce and tomato on a pita — it is the marinades and dressings that really set them apart. Dimitris make their own tzatziki, hummus and falafel, as well as the marinade for the meats. Though many have tried — rumours of industrial espionage abound — none have managed to replicate the Dimitris taste.

The prominence of these two pillars of Greek cuisine goes a way to explaining the rise of souvlaki in the city. My theory is this: even as recently as the 80s, there were very few options for dining out, especially cheap and cheerful ethnic food that we take for granted today. The central-city locations of Dimitris and Costa’s established souvlaki as Christchurch’s comfort food of choice; seeing their success, others went down the same route as it became easier to open a takeaway restaurant in the 90s. The Garden City was a souvlaki town — kebabs didn’t stand a chance. A highly scientific Google search backs this up; the Cult of Souvlaki has spread from the CBD into the suburbs, with more than 25 vendors, from New Brighton to Hornby, Redwood to Woolston.

Few of these outlets are run by Greeks, which can see some other variations thrown in the mix — not always a bad thing. The closest souvlaki to me comes from Rashid’s Persian Cuisine, while the Souvlaki King in Halswell introduces a bit more Middle Eastern spice and aroma. There is no questioning the Hellenic origins of It’s All Greek To Me though. I wander into the shop in semi-industrial Waltham and introduce myself to the owner, Penny Halloumi. She’s a Greek Cypriot, and makes a souvlaki that is traditional to the island. It’s another slight variation to add to the ones mentioned above. Instead of the pita being rolled into a cone, the bread is cut in half and opened up; the meat and salad is then placed into the pocket of the pita. It solves one of the great mysteries of the souvlaki: how do you eat the damn thing without getting incredibly messy? The pocket souvlaki means you get less bread, but you can also just pick it up and eat it like a sandwich.

But then maybe making a mess of yourself is just part and parcel of the souvlaki experience. I try to maintain an air of professionalism while I eat mine in front of Dimitri, though part of me just wants to furiously fork it into my mouth. I ask him how he eats one, thinking there might be some magical technique passed down through the generations. But alas, the only secrets that Merentitis keeps are what goes into his sauces and marinades, that has made his shop one of Christchurch’s most quintessential food experiences for locals and tourists alike.