On the unforgettable aromas that float through New Zealand’s cities and towns.

This is an excerpt from our weekly food newsletter, The Boil Up.

You could say a food market is a shrunken down version of the community it inhabits. Among the vegetables, fruits and herbs, they carry knowledge, social connections, culture, languages, history and trade. It’s the untamed multi-sensory experience of these places, more than the savings they offer that leads many of us to our closest weekend market for our produce shop.

Every time I’m at the market, in between searching for the cheapest kūmara ($4.99 last weekend) and the tenderest dou miao tendrils, I always find myself compelled to snap pictures with my phone. These photos serve no practical purpose; they’re simply my feeble attempt at capturing something I worry one day might be lost. But a picture can only tell us so much. When I scroll back through the images, the brilliantly fresh blush of radish bunches and the impressive abundance of choy sum, boy choy and ong choy are clear. But there’s a glaring piece missing from the entire picture: the smell. The aroma of keke pua’a frying in oil, the fresh fish heads, the piles of pungent alliums and celery, even the nuclear-hot long black that burst open all over my hands last Saturday.

The significance of food smells in public life and how fragile they can be has been on my mind for a while. It was perhaps sparked when I read about four Hindi writers who lamented the loss of gandh, or smells that typified their home cities, as globalisation and modernisation has seen traditional markets and bazaars disappear in favour of malls and multiplexes. “I feel it’s becoming very difficult to take care of one’s roots today. Once we forget our gandh, we forget our roots,” Shehar Dar Shehar, one of the writers, said at the 2009 Jaipur Literary Festival.

The smell of green chile roasting on an open flame is part of the fabric of the US state of New Mexico, and now a group is trying to protect it. This year they attempted to pass legislation to make roasting chiles their official state aroma – the first of its kind. “Chile is in the hearts and on the plates of all New Mexicans, and the smell of fresh roasting green chile allows us to reminisce on a memory of eating or enjoying our beloved signature crop. We like to call that memory a person’s ‘chile story’, and each of us as New Mexicans have a chile story,” said Travis Day, executive director of the New Mexico Chile Association.

It makes me think about the kinds of uniquely local food smells in the city where I live, Tāmaki Mākaurau. In the evenings, Dominion Road is heady with cumin and charcoal. Walk down Sandringham Road at any time and a bouquet of spices lingers in the air. In Newmarket, you can tell a lot about someone who makes a detour to avoid the York Street underpass, which is imbued with the smell of the busy fish shop underneath.

I grew up in Kingsland, and for most of my life I have wondered about the curious burnt toast smell that filled the air of the gully at certain times of the day. At school we’d speculate about the mysterious olfactory phenomenon. It’s only embarrassingly recently that I realised that the smell is Atomic Coffee’s roastery, which opened a year after I was born. Living in the area for the majority of my life means that smell has become entangled with my sense of home and identity.

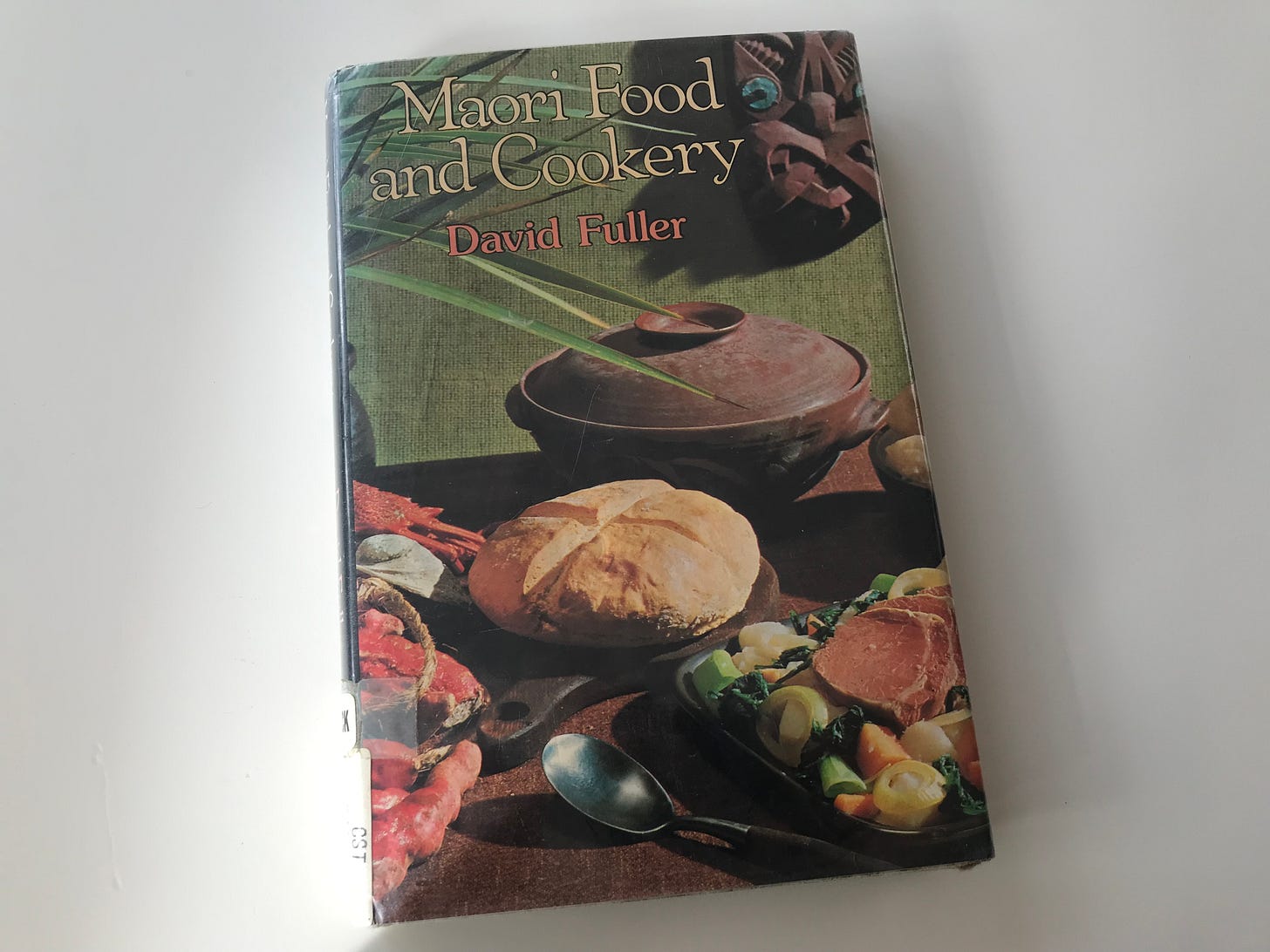

While many contemporary aromas are at risk of being lost, I can’t help but wonder what pre-colonisation scents we never got the chance to smell. I recently borrowed a book from 1978 called Māori Food and Cookery, by Pākehā author David Fuller. Parts of it are admittedly dated, but the book provides an invaluably detailed account of traditional kai Māori and how it was prepared. Reading it this week has made me wonder what the nikau cooked in hāngi until it formed brown sugar crystals might have smelt like. Or whether the pungent smell of kooki or dried shark would have permeated its immediate radius. And how embedded the smell of fish prepared fresh from the moana might have been in everyday life. Or how totally ordinary the smell of the ngahere might have been when it came to collecting kai. Then there’s kānga pirau, or rotten corn, affectionately named after its contentious aroma.

The smells of kai Māori might be less omnipresent than they once were, but they obviously haven’t entirely disappeared. Ngāpuhi perfumier Tiffany Witehira, of Curio Noir, has a perfume named Pūrotu Rose, an expression of the fragrant notes of her grandfather’s tangi: the smell of smoke and hot soil from the hāngi and roses adorning the tables in the wharekai.

It’s a regularly repeated fact that smell has a stronger link to memory and emotion than any of our other senses. Something to do with those parts of our brains being so close together. When we’re considering kai and its links to our history, it seems worthwhile to consider and to protect the shared food smells that give perfumed colour to our daily lives. To lose those smells is to lose memories.