A self-anointed expert explains why the death of a sandwich chain and New Zealand’s failure to sustain a thriving egg sandwich economy has nothing to do with people working from home.

It’s almost impossible for me to pick a favourite food but the sandwich would be right up there. Almost anything can be made better when stuck between two pieces of bread. Once a year I look at luncheon in the supermarket and wonder if describing the thin pink and white sandwiches of my childhood as “gross” was ungrateful and foolish.

Sometimes, the highlight of a Friday night for me is planning the sandwich I will make and eat the next day. I also love to buy sandwiches. I have spent an extraordinary amount of time wondering why this country can not sustain a chain of sandwich shops that realises the triangular dream of good, cheap and fast.

Perhaps the closest we’ve gotten to that kind of ubiquity in New Zealand is Wishbone. The chain, modelled on the UK’s ubiquitous Pret a Manger sandwich shops, was put into liquidation this month. Its stereotypical customer apparently resembled the result of a stock image search for “time-poor office worker” and so Wishbone’s failure prompted some to diagnose central Wellington as chronically ill, its empty streets now filled only with the pale ghosts of those time-poor office workers, now doing their office work from home. The end of Wishbone was also cited as an example of the country’s stagnant economy.

Online, pushback ensued. The most common contention was that Wishbone sandwiches were in fact decidedly “mid” and expensive. There’s also a fair argument to be made in favour of irrevocable change wrought by this century’s main character, the global pandemic. In an effort to understand what killed Wishbone, you could also give competition, market forces, changing food preferences and changing culture a cursory glance.

On hearing the Wishbone news, I did pour one out for their chicken and almond sandwich. That sandwich was absolutely fine – solid, reliable and only occasionally soggy. It wasn’t cheap, just as the “posh cheddar and pickle” at Pret isn’t cheap, but as one city centre worker remarked to The Post, “you can’t get a cheap sandwich these days”.

Unfortunately for everyone, I have been to Japan recently.

Imagine a Venn diagram consisting of three circles. One is safe and delicious and contains sandwich lovers. In the second, you’ll find people who went to Japan for three weeks and returned as Nipponophiles, a thin layer of pseudo-knowledge about the culture of Japan calcifying in their brains. In the third circle is a smaller group of people who talk about demography, population and Productivity Commission reports at parties. Like a troll under a bridge waiting to bore you shitless, I live in that intersection.

Technically, I have been banned from writing about my holiday to Japan. A day or two after getting home, it becomes apparent to anyone with an ounce of self-awareness that the rules of coming back from Japan are the same as the rules of fight club.

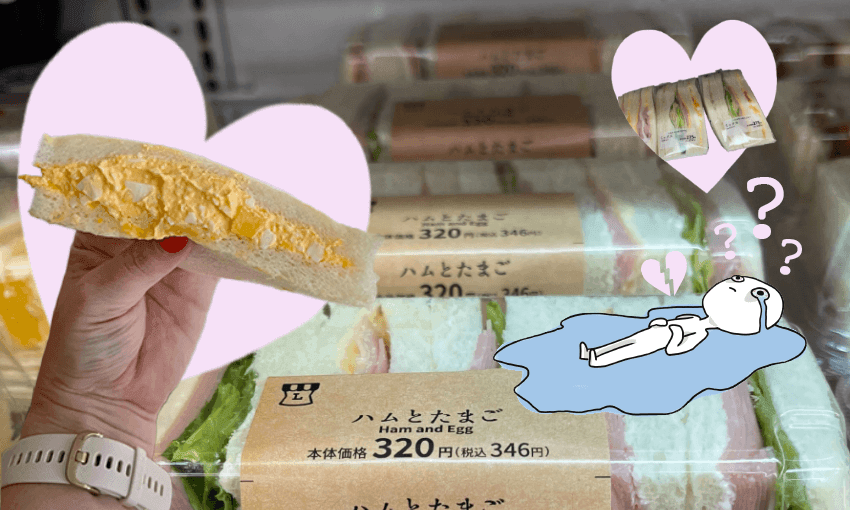

I have been granted an exception to this rule to write an ode to the Konbini Tamago Sando, otherwise known as the convenience store egg sandos of Japan. It was pitched on the basis of its proximity to the Wishbone news. It’s not my fault it’s impossible to explain my half-formed thoughts on the economics of the sandwich without telling you they arrived after the salubrious experience of sitting on a Japanese electric toilet and that they crystalised during relaxing rides on bullet trains, or Shinkansen.

The convenience store egg sando is perfect. It’s made using Japanese milk bread, eggs, and what I assume is the exact right amount of kew-pie mayo. It’s tangy, soft and probably bad for my gut health. The best thing about it is that it costs 258 yen, or $2.98 NZD.

I started most days of my holiday and now retrospectively classified sando fact-finding mission with a FamilyMart sandwich. It was washed down with a gelatinous B12 drink that you apparently piss out without absorbing any vitamins. I was at the top of the game on this diet. It was on a train between Tokyo and Kyoto, while eating this breakfast of champions, that I began to ponder why it was that Japan could turn out hundreds of thousands of these perfect sandwiches each day and sell them as cheaply as they did and New Zealand could not.

You can buy these sandwiches at all the convenience store chains in Japan. These stores are all franchises of giant corporations. One of them, Lawson, is owned by the Mitsubishi Corporation. They are not corner dairies and they are not powered by the plucky entrepreneurial spirit that drives many New Zealand businesses. The FamilyMart egg sando stole my heart but it could just as easily have been the ones from Lawson or 7-Eleven. They are exactly the same in every single store and the stores themselves are absolutely everywhere. Sophisticated point-of-sale systems monitor stock levels and no sandwich ever tastes like it was made yesterday. They are the realisation of the impossible triangular dream. That they are literally triangular is almost too much to bear.

As I glided off one perfectly on-time train and onto another it dawned on me that leaving Japan and returning home would mean leaving these perfect sando and trains behind. Glancing around a train station it became apparent that Japan was filled with people. Many more people than New Zealand. Unsatisfied with sharing my emerging theory of sandwich economics based on street-level observation alone, I googled some Census data.

According to the Statistical Bureau of Japan, the population of Japan as of February 2023 was 124.6m. According to my general knowledge, New Zealand has a population of 5.2m. By god, I thought, ignoring a range of other possible social, cultural and economic factors, it’s economies of scale. And with that, a theory of sandwich economics and this entire article was born.