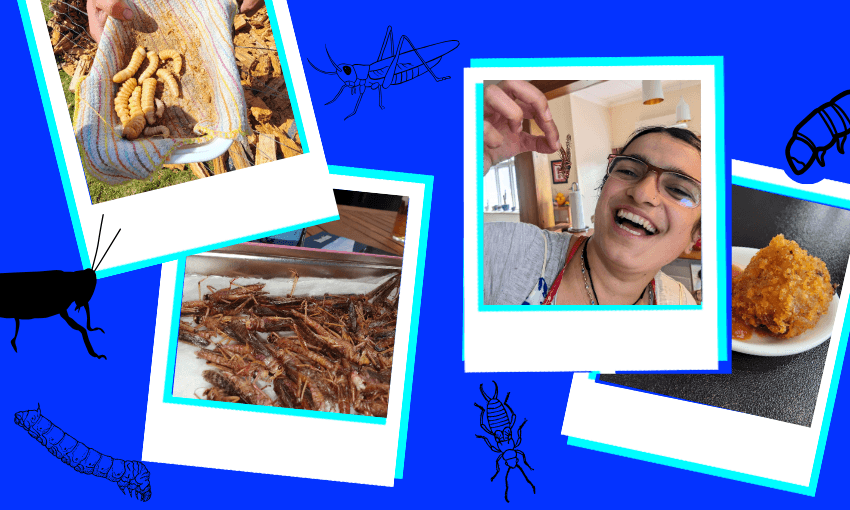

Summer reissue: Insects have been the ‘next big thing’ in food for the last decade, but will we ever have an appetite for them? Shanti Mathias investigates – and tastes some bugs.

The Spinoff needs to double the number of paying members we have to continue telling these kinds of stories. Please read our open letter and sign up to be a member today.

“I am completely certain,” I declared to my colleagues, “that if people had to kill the animals they ate, there would be much less meat eaten in the world.” Everyone nodded agreeably; no one offered to put the locusts in the work freezer on my behalf.

The locusts had arrived in a ventilated tube from Otago Locusts, a Dunedin-based locust farm, several minutes earlier. Inside, khaki insects as long as my thumb nibbled on grass that Otago Locusts owner Malcolm Diack had provided them for the journey. They made a subtle clicking, chirping sound, with shimmery patterns on their translucent wings, and twitched their antenna as they munched and scrambled over each other, their black eyes bright.

I had wanted to write about the locusts because insects have been the “next big thing” in food for at least the last decade. It’s been pointed out, again and again and again, that insects could be an excellent, nutritious source of farmed protein. Insects can be eaten whole, meaning a much bigger proportion of the animal is eaten than animals whose guts and skin are removed. Insects are much less resource intensive to produce: while estimates vary, one common statistic is that producing a kilogram of beef requires 15,000 litres of water (the beef industry disagrees). Insect protein, meanwhile, requires a third of the land and a fifth of the water required for beef – and almost all of that land is for the feed, rather than the insects themselves.

Eating insects is normal for many people: it’s estimated that two billion people eat insects regularly. “It’s such a good option for sustainability, and locusts can be grown here, without needing to be imported,” Diack says, enthusiastic.

On this basis, eating insects makes perfect sense – yet in New Zealand, insects are a one-off novelty, a gift to gross out your nephew, not a consistent source of food. In 2019, Bex de Prospo wrote an article for The Spinoff about closing Anteater, her edible bug business: “Maybe in five years, New Zealand will be ready for an edible insect revolution and we’ll have delicious bug burgers on our supermarket shelves.”

Five years later, this vision hasn’t come to pass. In the years since, more insect businesses have come and gone: a group of University of Otago students launched Ento, a locust powder business that initially bought locusts from Diack, but it isn’t currently operating. A directory website, Bugsfeed, links to various New Zealand websites which no longer exist. Eat Crawlers, the other main insect retailer in New Zealand, was just having its ownership transferred to a Singapore-based company when The Spinoff got in touch, and its new director didn’t respond to requests for an interview.

The most long-lasting insect businesses have instead turned their attention to the animal food industry. This includes Otago Locusts: Diack sells more locusts to gecko owners and zoos than curious punters, high-profile chefs or, most elusive of all, people who incorporate insects into their day-to-day diets.

But the hype remains. Accordingly, eating insects has at times been treated as a concept worthy of Silicon Valley hype and funding cycles, with investors putting more than $1.3bn into insect farming companies as of 2023, mostly in Europe. While this is much less money than other alternative proteins, including Impossible Foods and the publicly listed Beyond Meat, it does indicate a wider sense that insects could be big business.

The non-profit sector also touts insects as an effective alternative protein, with a major report from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation in 2013 examining invertebrates as a future food source. However, this particular document has also caught the attention of online communities – in a bad way, becoming the focus of online conspiracies that people will be forced to eat bugs.

The conspiracies don’t help, Diack says. Otago Locusts is already a small operation, but the bulk of its orders come from pet owners and zoos, not hungry people. The locusts live inside two shipping containers at the back of Diack’s Dunedin property, fed by spray-free grass he gathers locally. “Someone commented [on Facebook], ‘you’re growing the plague in your backyard,’ but I’ve been doing this for years, it’s all under control,” he says.

Locusts can actually reach New Zealand independently, but as their profile on the Landcare Research website notes, they don’t “reach plague proportion in New Zealand, probably because temperatures are not high enough to trigger swarming”. “If they got outside in winter, they’ll just stop and go to sleep until a bird eats them. If they got outside in summer, they would be able to fly and wait for a bird to eat them,” Diack says. He has to keep his “little locust farm” carefully temperature-controlled, and points out that he would have a much bigger operation if he did have funding from international organisations. “No one is going to force you to eat an insect,” he says.

Some countries have more incentive to investigate insects as a protein source. Singapore, which has a slightly larger population than New Zealand but only 2% of the land area, leads the way in alternative protein. Last month, its government explicitly approved 16 species of insect as fit for human consumption. However, this doesn’t mean that raising insects for food is illegal elsewhere – Diack received approval for his locusts being sold as food in 2016, after raising locusts as pet food since 2009, and the Food Standards Australia and New Zealand authority has guidelines for labelling insects as a food source, even though New Zealand has no explicit legislation that deals with eating insects.

Of course, insect eating has always taken place: Māori ate insects long before colonisation, a practice that has continued with huhu grubs. “We experienced a big loss of matauranga around insects after colonisation,” says Chrystal O’Connor, a PhD student at Lincoln University who is studying how native insects are a source of sustainable protein. She recently published a paper looking at Māori attitudes to eating insects. “I heard lots of stories about how people remember their grandparents eating or talking about huhu grubs,” she says. Forty-one percent of her participants named insects as a significant source of kai pre-colonisation, and 94% of people mentioned huhu grubs as an edible insect.

But it wasn’t just huhu grubs. “We were hunter gatherers,” O’Connor says. “We ate cool insects!” Mānuka beetles, for example, were crushed into powder and mixed with raupō pollen to form a high-protein food. O’Connor has identified about 15 other insect species which were regularly eaten by Māori.

While huhu grubs are still eaten, they’re rarely a cornerstone of people’s diets. “They’re more like a novelty, if you go camping you might fry some up for the experience but not include it in your everyday diet,” O’Connor says. She’s currently raising caterpillars – chosen because about 28% of the insect species consumed around the world are caterpillars, and they grow fast – and feeding them kawakawa and mānuka leaves to see if the rākau rongoā (traditional Māori medicinal plants) give the animals additional medicinal value as well.

O’Connor gets one species of caterpillar eggs from a supplier; the others she gathers in the wild, as they haven’t been raised for eating before. They live in 1.8 metre enclosures – very different from the vast fields needed for red meat – and feed on leaves gathered from the wild. “Taste and texture wise, [the caterpillars] are more familiar to other foods – they’re not mushy like a huhu grub would be,” O’Connor says.

In her research, O’Connor found that 87% of Māori she surveyed would be willing to eat insects. Diack says that there’s consistent interest in at least trying to eat insects. “I could stand on the main street of Dunedin harassing people – I think it would be the same, at least 50 to 60% of the population would be okay with eating insects.” There’s also the fact that even if you haven’t tried a huhu grub on a hike, you’ve probably eaten insects at some point in your life. That old myth about swallowing eight spiders a year isn’t true, but there are often small amounts of insects in food (at a low level that doesn’t pose a health risk).

Eating insects as a novelty, or by mistake, is one thing, but what will it take to make insects a widespread part of New Zealanders’ diets? Even the locust farmer isn’t munching on wings and legs very often. “I don’t actually eat that many locusts, because they’re my stock,” Diack says.

Many insect-food businesses sell processed insect products, like crickets ground into flour and added to pasta, or added to soup and energy bars. Without carapaces and wings to look at, these products avoid at least some of the ‘ick’ factor which many people associate with consuming arthropods. But while sizzling a huhu grub from a log in the forest is free, most commercial insect-farming operations are still small scale, and therefore expensive.

Diack charges $1 for fully-grown winged adult locusts, although smaller hatchlings are cheaper. On sale, Eat Crawlers’ cricket pasta is $4 for 250 grams, while 100 grams of mealworms are $33 – much more expensive than non-insect options. The cost of farmed insects is a major barrier to new businesses trying to sell insects. Beyond specialist suppliers, farmed insects are hard to get – not, for example, available at the dairy or supermarket. (The Spinoff asked Woolworths if the supermarket chain was interested in stocking insects; a spokesperson said that “there are currently no plans to introduce edible insects”, but added that they were open to consumer demand.)

O’Connor, though, is hopeful. “There are chefs using insects and making them look delicious, and if people know the type of insect was eaten in the past, they’re more likely to try it.” The novelty is a good thing: it can get people to put something they haven’t been acculturated to think of as food in their mouth.

Diack, meanwhile, likes to serve deep-fried locusts at parties. “I always find a couple of drinks increases the enthusiasm,” he says. He thinks widespread, commercial insect consumption in wealthy countries could be 10 or 15 years away – helped along by the climate crisis necessitating that the global population eats less traditional meat.

It’s not like diets haven’t changed massively before. As Alex Smith documents, a few decades ago it was unusual to eat raw fish in New Zealand, and now sushi is incredibly popular. After the colonisation of the Americas, potatoes, tomatoes and chillies were distributed around the world, and are now integral to many culinary traditions. And as O’Connor runs up against in her research, Māori food changed irrevocably after colonisation, with foods like fry bread adapted to indigenous traditions.

The cultural power of learned eating preferences is still incredibly powerful. I don’t eat meat, but in concept, I have no issue with eating insects – I’m definitely interested in alternative, more sustainable forms of protein. I feel a pang of moral guilt as I put Diack’s crawling locusts in the freezer, even though I know the industrial agriculture which produces most of my food relies on mass insect death via insecticides. These insect deaths, like the slaughter of animals usually encountered as meat in plastic packets, happen out of my sight, but these ones I’m responsible for.

A few hours after putting the locusts in the freezer, I pull them out, now still and thoroughly dead locusts out of the freezer. My moral concerns are forgotten: instead, I feel my stomach churn at the thought of having to chew and swallow the insects.

Diack likes to call locusts “sky prawns” to make them more appealing. In fact, the protein in locusts is so similar to crustaceans that people with seafood allergies usually can’t tolerate the insects either, and when I fry the locusts, they turn a shiny red colour, just like a lobster.

As I shake them out of the box and into the oil, I feel a little repulsed. The wings turn brittle and shiny; the thoraxes curl in the heat. Once cooked, I scatter some salt and paprika on top and get my flatmate to hype me up. I pop the insect into my mouth and bite. Once I can’t see it, the disgust fades: there’s not much to it: a mild nuttiness, the slightly chewy body and crunchy legs. It isn’t a transcendent culinary experience – I haven’t tried very hard with the seasoning – but it is completely fine, the kind of thing I could easily eat absently while reading about a murder-mystery train ride or watching a movie.

At the start of the day, the thought of eating insects had seemed unappealing in reality, if intellectually interesting. But with a locust chewed and down the hatch – and then another, and then another – I wonder what I was so worried about. Just trying an insect makes me see how easily this food source could be integrated into what we eat already. I start imagining: what would the locusts be like with some tangy soy sauce, stirred through a rice bowl? Could I caramelise them and crumble them over porridge?

O’Connor is excited about the possibilities of medicinal native caterpillars becoming a lower-emission, high-value export. But it’s a conversation with her uncle that reminded her that changing people’s feelings about eating insects is possible too. Like other members of her Waikato farming family, he’d asked her for years why she would research insects as food. But on a recent visit home, her uncle’s perspective had changed. “He said, ‘if you’re researching it, I’d better have a go.’” Maybe one day soon, she’ll be able to take him to a local restaurant so they can all eat insects together, just as ordinary as a boil up or a roast.

First published August 28, 2024.