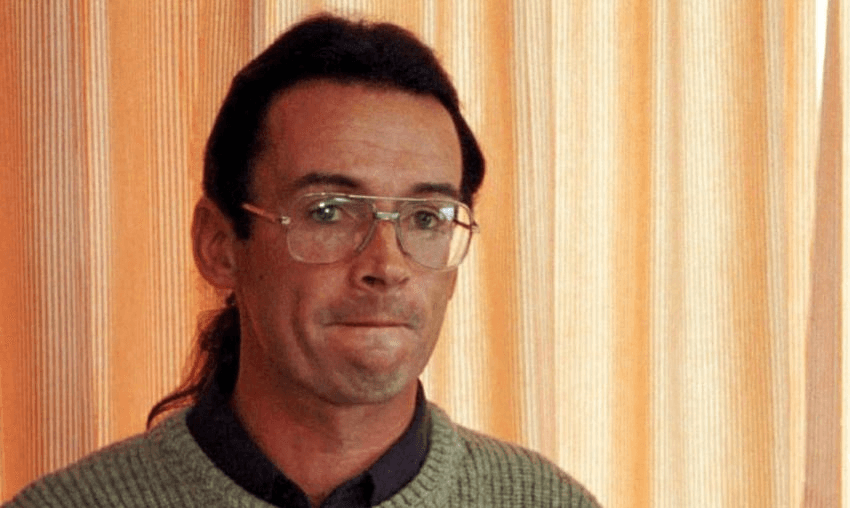

Despite two unsuccessful appeals against his convictions for child sex abuse, doubts around the reliability of the evidence against Peter Ellis have hung heavy for almost three decades. Yesterday it was announced that the Supreme Court would give him an opportunity to clear his name.

What’s all this then?

Peter Ellis, a convicted child sex offender and alleged satanist, has been granted leave to take his nearly 30-year fight to clear his name to the Supreme Court.

Ellis was charged and convicted of abusing seven children at the Christchurch Civic Childcare Centre in 1991, and served seven years of a 10-year sentence.

He has always maintained his innocence, refusing to attend parole hearings on the grounds he would have had to admit to the crimes to secure an early release.

His case has attracted widespread condemnation, with many calling it one of the worst miscarriages of justice in New Zealand.

Ellis has been diagnosed with terminal bladder cancer and reportedly only has months to live.

The Civic Childcare Centre? Sounds familiar.

The case was widely seen as New Zealand’s own manifestation of a wave of child abuse hysteria that swept through the western world in the 80s and 90s.

Hundreds of innocent childcare workers were convicted of bizarre, often impossible crimes, mostly related to satanic, ritualistic sexual abuse. Critics say these cases were almost invariably based on the coerced and inconsistent testimony of young children.

The Ellis case created an atmosphere of moral panic in New Zealand, dividing households. The convictions and coverage only exacerbated the disparity of genders in early childhood care, which largely persists to this day.

Satanism? Ritual abuse? What?

The claims against Ellis at times read like something out of slasher fiction. As Beck Eleven graphically described in North & South in 2015:

“During formal police interviews of 118 children, allegations were made that Ellis had taken youngsters on sex safaris, handed them to Asian men for sex, smuggled groups through tunnels and into dungeons. He had apparently thrown a bound child into the deep end of the QEII pool.

“Children claimed they’d been forced to drink urine and eat faeces, and had been hung in cages. One child said they were made to kick each other in the genitals while adults stood in a circle around them wearing black and white clothing and playing guitars.”

As with international cases of a similar nature, police consistently employed flawed investigative strategies. For example, they repeatedly interviewed children over a period of months, a technique no longer employed, and by their third or fourth interview, the children’s stories were near ludicrously fantastical.

One boy who initially claimed Ellis had smacked him on the bottom and touched his genitals asserted in his fifth interview that Ellis’ elderly mother had hung children in cages from her ceiling.

A six-year-old girl told police that the children had been abused by men called “Spike, Boulderhead, Yuckhead and, um, and Stupidhead.”

So why did anyone believe them?

Ellis advocate Lynley Hood said in her book A City Possessed that the campaign against Ellis amounted to a “witch hunt”.

She wrote: “from the police point of view being a gay man was a red flag. And from the militant feminist point of view that was going on at the time, being a man was a red flag. So there were two marks against him already.”

And it wasn’t just the police who thought as much. In 1993, Graeme Lee, then minister of internal affairs, told Paul Holmes that “homosexuals had unarguably an unnatural behaviour … In context to [the Ellis case], surely it stands to reason there is a predilection to paedophilia or child sex.”

Ellis’s supporters also expressed strong misgivings about the prosecution’s star expert witness Karen Zelas, a specialist in child sex abuse cases. Zelas had strong views on child abuse, telling the court that if a child said they’d been abused, it was true, and if they said they hadn’t, it could be denial and was also likely true. Zelas believed stomach aches, tantrums and bedwetting were all signs of child abuse.

Now a full-time fiction writer, Zelas was blamed for a miscarriage of justice in a seperate sex abuse case in 2003 when she was found by the Court of Appeal to have “gratuitously” exceeded the scope of permissible expert opinion.

Is this his first time back in court?

Ellis has twice appealed to the Court of Appeal, once after a referral by the governor-general.

The first appeal in 1994 quashed three of his convictions, after one of the child witnesses said she had lied, but the second appeal against the remaining 13 charges was dismissed in 1999. There was a Ministerial Inquiry in 2001 by Sir Thomas Eichelbaum, which concluded there was no miscarriage of justice. There were also unsuccessful petitions to parliament for a Royal Commission in 2003, 2008 and 2014.

With only months to live, Ellis’ fight to clear his name takes on a new urgency. It will be his last chance.