In recent weeks, several American editors have been exposed for their toxic work practices. For a New Zealand journalist who spent a decade ensconced in this deeply dysfunctional culture, their day of reckoning comes not a moment too soon.

The worst behaviour I ever saw from a grown man was at The New York Post. He was an editor so toxic that staff members warned me when I was moved to sit within spitting distance of him. A week or so later, he threw a tantrum of monumental proportions when my proofing printouts – I was editing the newspaper’s New York Fashion Week supplement – touched his work area. The six-foot-something baby went red in the face, stamped his feet and banged his fists, screamed F-bombs in front of 30 colleagues and called me a “bottle-blonde strumpet” when I asked him not to swear at me. Afterwards, I was chastised by a senior female editor for prompting one of his legendary outbursts.

Maybe the big baby will lose his job this month. Plenty of other men behaving badly in the American media have.

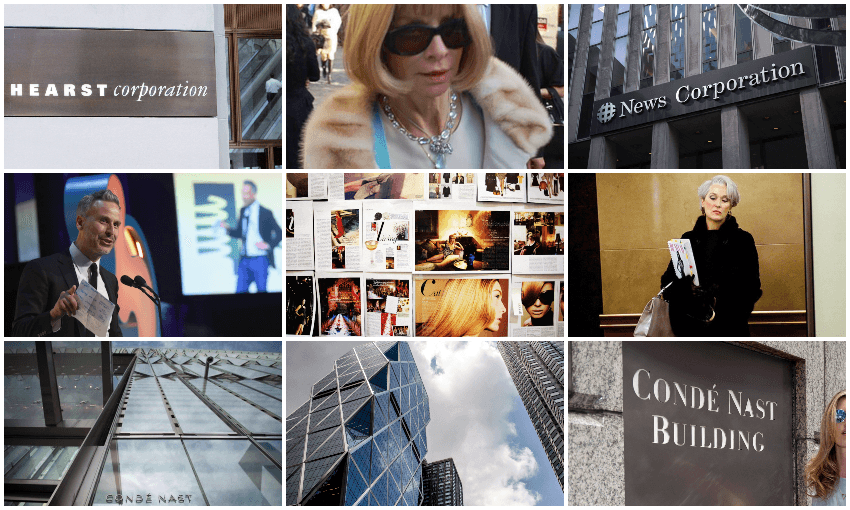

Last week Adam Rapoport, editor of Condé Nast’s Bon Appétit and a white dude who not only thought it was OK to dress up as a cliché version of a minority for Halloween but also to ask his African-American editorial assistant to clean his golf clubs, resigned after staff became mutinous. He walked the plank around the same time editors at The New York Times and Philadelphia Inquirer who printed pieces that showed their bias and tone-deafness towards minorities, people of colour (POC) and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Yes, Rapoport sounds terrible. His boss, Anna Wintour, comes across as terrible too in both the novel The Devil Wears Prada and The September Issue documentary. But they’re no worse than many of the editors – men and women with outsized egos and out-of-whack values – that I laboured for over 10 years working in magazines and newspapers in New York City in the early 2000s.

At Hearst, publishers of Harper’s Bazaar and Esquire, I freelanced for an editor who had such bizarre rules about copy that it was impossible to write a grammatically correct sentence. It didn’t help that she turned up to the office once a fortnight or so; the rest of the time her palatial, glass-walled office sat empty and we fretted about what she would say about the pages we put together.

At Condé Nast, the class system dictated that minions like me weren’t allowed to talk to the editors in chief if we met in the elevator. If Anna Wintour, the Kanye West of publishing, entered a lift, you had to get out to save her from riding with the plebeians. When Ruth Reichl, editor of Gourmet and my publishing hero, strolled into an elevator that was empty except for me one afternoon, I wanted to say, “I love you; I’ve read all of your books”. But the threat of her wrath, or the wrath of someone in HR if she reported me, meant I stayed schtum. She exited on the ground floor of the shiny skyscraper and wandered out to her town car where her chauffeur held open the door.

Anna Wintour had a table permanently laid with linen and fancy silverware in the Condé Nast dining room. The restaurants and cafeterias were amazing in those days; you could dine like a king for very little, and even though everyone knew they subsidised the food so we’d never leave the buildings, it felt like a real perk of the job. At Time Inc., the restaurants had stations dedicated to all types of food – Mexican tacos, Indian curries, south-western barbecue – but that was where the companies’ diversity seemed to begin and end. In every job I had in publishing, my colleagues looked just like me: stressed, under-slept white women in their 20s, 30s and 40s. Shamefully, I can remember every POC I worked with in those days because there were so few of them.

At the New York Post, there were lots of old white guys to balance out the young white women, particularly in the sub-editing department. I dreaded taking my pages to them to be proof-read. I’d stand in their pod, hovering, waiting for someone to acknowledge me while they studiously ignored my presence. It was like being hazed in a retirement village.

But it was on a weekly magazine that the treatment from the higher-ups was the hardest to take. Most nights we worked until 9 or 10pm. On many nights, just before going to print, our editor-in-chief would tell us that she was binning a story and we needed to start again. You couldn’t get to a doctor or do any supermarket shopping during the week. You couldn’t even get away from your desk to get your own lunch. When my parents visited from New Zealand, I dared to leave work at 7pm to take them to a Broadway show. Once when I sent a staff writer home to New Jersey to be with her dying dad, I was told to make her work that weekend (I refused).

Every day someone would be crying in a bathroom cubicle. I never cried, but I stopped sleeping; my boss suggested I get a prescription for Valium so I could handle the job. We all survived, but like any abusive relationship, it took its toll.

There were nice bosses, at Time Out New York and at Time Inc. And let’s be honest, there are terrible bosses in New Zealand’s media companies too. Before I moved to New York, I was a staff writer at a current affairs magazine. The editor recruited the female employees to help her tidy her house before she hosted team drinks one summer. Even then I knew enough to know that was some demeaning, sexist bullshit.

Twenty years later, at my last editing job in New Zealand, the publisher told me she’d considered putting tracking devices on our cars to make sure we were always working in work hours. The more things change, the more they stay the same.