Refugee advocates are celebrating a win with a promised increase of the quota under the new government, but those refugees who get here are still facing years-long waits for family to join them. Tessa Johnstone reports

“That’s me!” Mohamed* says, with a grin.

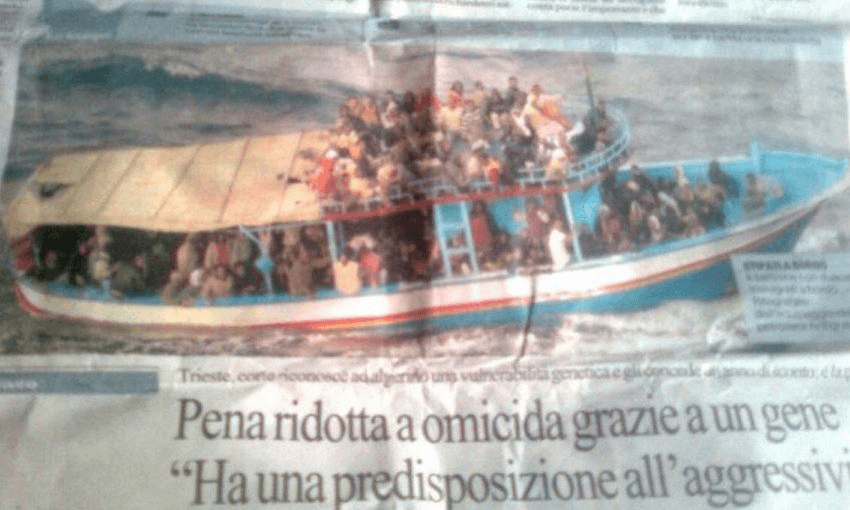

He’s pointing to a grainy photo of a clipping from a Maltese newspaper. Through the cracks on his iPhone screen I see a brightly-coloured boat bobbing in choppy waves. People spilling out of every side of it. Mohamed in a white singlet, leaning off the side, squinting at the photographer in the helicopter above.

They’re shortly to be rescued after a breakdown during a storm in the Mediterranean Sea. They’ve come from Libya and they’re not making it to Italy. While they don’t know it yet, they’ll be detained for three months in a Maltese military camp before being flown back to their home countries. On arrival, some will be tortured and imprisoned.

Mohamed says there were 255 people on that boat, including pregnant women, children and elderly people from a dozen countries, most fleeing danger of some kind. While they never made it to Italy, all made it off the boat alive, a fortunate turn of events for those who risk their lives for a shot at asylum in another country.

It takes him two hours to tell me the full story of his refugee journey. It took him seven years to get to New Zealand, including five years in an Eritrean prison after that ill-fated boat trip. It then took him eight years to work through the immigration process in New Zealand to bring his family to join him here.

It’s not uncommon for a former refugee to wait that long to be reunited with family in New Zealand.

Sponsoring refugees can spend years waiting for a letter from Immigration New Zealand to let them know if their application to bring family has ticked all the boxes or not, then months waiting for a case officer to be assigned, then another year working through the documentation and checks required.

In some cases, the sponsoring refugee has to prove they can provide secure housing for the family and then save thousands of dollars for the airfares to get them here.

Many families manage to get through those hurdles but then arrive to no support from the usual refugee resettlement support services, because the services are not funded for family members of refugees, although their needs are often the same.

The prolonged wait causes severe stress for family members here, many of whom are worried about their husband’s, or children’s, or sister’s physical safety in another country.

Former refugee Christalin Thangpawl says while most are grateful for a life in a country where there’s peace, it’s not enough. “We appreciate that the country saved our life, but if you really care about people then when they get here, they must be able to get family members here.”

There could be change on the horizon, with a review of refugee family reunification policies one of the Green Party’s wins under their deal with Labour.

“They’re being treated like it’s an ordinary immigration process, but it needs to be looked at as a refugee situation,” says Greens immigration spokesperson Golriz Ghahraman.

“If we are consistent, we have to recognise that the crux of a refugee determination is that they’re people who have to leave or flee and so there’s urgency. It’s not at any point been an optional, let’s move for a better life, situation.”

Amanda Calder, lawyer and chair of the Refugee Family Reunification Trust, says the process simply takes too long. “On a good day you’re looking at several years, sometimes four or five years. It’s not going to be fast.”

The current system puts families in a queue – a very long queue, jostling with hundreds of other at-risk families. There are currently more than 1400 applications, representing some thousands of family members, waiting to be processed under the Refugee Family Support Category. Immigration NZ estimates it will take at five years to work through them.

“It’s not fair if the queue is that long, waiting and hoping and stuck in a rut waiting for family. Meanwhile, goodness knows what’s happening to the family members left behind in refugee camps and similar awful situations,” says Calder.

A former refugee she is working with now first applied to bring his family here in 2012. He was finally given the ‘invitation to apply’ for his family’s visas in March 2016. That’s a four-year wait simply for a yes or no from Immigration NZ, and his family still haven’t arrived.

The Habte family were split apart while fleeing Eritrea. Two siblings came to New Zealand in 2008, while two were still stuck in Sudan. They were reunited here in 2017.

Senait Habte, a new mother, is lost for words when I ask how it felt to finally have her family with her here. Were you happy, I ask?

“Very much, very much,” she laughs. “It feels like home now. Before you were feeling alone all the time, feeling lonely. At least now we were together on Christmas Day.”

Mohamed, who wanted to bring his sister, brother-in-law and their children to New Zealand, said Immigration NZ took two years to let him know if his initial application had been accepted or rejected.

Once he started the visa application process, he says, the department would take months to respond to his queries or acknowledge paperwork submitted, yet would ask that he met short deadlines or risk the application being declined or expiring.

Despite the challenges, he succeeded in getting his sister to New Zealand last year. Mohamed is reluctant to complain, but admits it was a difficult wait.

“I’m very happy now, I feel like something big is behind me. Before, you were longing. For me I feel like I have come 360 degrees.”

The refugee family reunification policies and processes have reportedly improved over the years, but are still difficult to navigate. New Zealand usually takes 750 UNHCR-verified refugees a year under its quota system right now, and the government made an election promise to double that in the next three years.

Some of those refugees may then be eligible to apply to bring their partners or children to New Zealand in a future quota intake – but only if they declared them the first time they were interviewed by UNHCR, and in the case of children, only if the children are still under 24.

There are also 300 places each year in the Refugee Family Support Category, which requires people to meet a different set of criteria altogether. The main criteria is that they don’t have any immediate family in New Zealand, that they’re alone. The sponsoring refugee has to meet a number of other conditions, including finding housing for the family for two years, and meet the costs of medical checks, application fees, lawyers and airfares.

It then gets more complicated – there are currently two tiers of registration within the Refugee Family Support Category.

Tier one is for anyone who came in the quota, alone or only with dependents, to apply for family members to come. If Immigration NZ doesn’t fill those 300 places with eligible family members it can select applications from a second tier registration.

Second tier registration has only opened twice, and each time has only opened for three days at a time. The paperwork can’t be lodged in person, and it can’t be lodged even a day early, or obviously, late.

In the most recent round at the end of 2017, Immigration NZ got more than 1300 eligible registrations representing more than 6000 family members. It was a 75% increase on 2012 and the department estimates it will take five years to process the applications.

Immigration NZ attributes the long processing times to missing information. “Many applicants live in isolated areas where the transfer of information can take time,” says Immigration NZ’s Andrew Lockhart.

“Information which INZ requires to make decisions on applications include health/medical, documentation to evidence family ties, accommodation plans and document requests for verifications. Once information is provided to INZ, it is often necessary to seek responses from the applicants and the need to provide comment or further information can add to the processing time frames.”

Megan Williams, senior lawyer at Community Law Wellington and Hutt Valley, says that’s true, but it’s not the full story. Refugees do have difficulty getting the documentation needed, often because they have fled in a hurry without papers or haven’t lived in their home country for a number of years.

“But there’s also a resourcing issue with Immigration NZ and not enough case officers to deal with the applications, they seem to have very heavy workloads,” says Williams.

She says the long processing times are a huge strain on former refugees in New Zealand. “It can be really distressing for people. I’ve had cases where their parents haven’t seen their kids for five years, they may have been separated from their children for a number of years before they even get to New Zealand. The process of reunification can take another three years. The impact that has on families … The flow-on effects can be pretty huge.”

At times, Williams says, she has been extremely worried about the physical and mental health of clients she is working with.

“I had one client who could not sleep for years and she did things like forgetting to turn the element off. Her teenage daughter told me she was worried she was accidentally going to walk in front of a car because she’s so tired and so stressed and so anxious. This case took a really long time.

“The difficulty for some clients as well is not just the separation and the length of time it’s taking but their family members might not be living somewhere that’s very safe.

“In this case, the children, teenage boys, were in Sri Lanka. The Sri Lankan army was still rounding up teenage boys, they were disappearing, they were being beaten, and she was petrified.

“But the boys made it here. When I saw her afterwards, she looked about 10 years younger. She’s opened a restaurant. She’s gone from barely able to function to being quite a strong person in her community and really thriving.”

Williams says for former refugees, having family safe and alongside them is vital to resettlement. “Once people are here, that gives them the base to be able to start their life. People can’t move on until their families are safe.”

New Zealand Red Cross is the main provider of resettlement support for quota refugees for their first year, and sees it as a major barrier to settling in. “How do you settle when important people in your family are in really difficult circumstances or in danger?” says Red Cross’s client services national lead Rachel Kidd.

Some former refugees have existing mental health issues, or post-traumatic stress as a result of the violence and disruption they have been through – but some are simply there because of the anxiety caused by being separated from family.

“It provides stress for people,” says Kidd. “Most refugees who come here manage, some people will need to have counselling, may need to have counselling for a long period of time around how to manage this situation. It makes people anxious and it can make people incredibly unhappy.”

Refugee families are overjoyed to be reunited, but there is a significant burden for the sponsoring refugee to bear on their arrival.

While quota refugees spend six weeks at the Mangere Refugee Resettlement Centre, getting a crash course on New Zealand, basic English and being connected with vital services, those who come through the Refugee Family Support Category go straight to the sponsoring family member.

Quota refugees are supported by both volunteers and professionals for at least a year through the Red Cross refugee resettlement programme, but family reunification cases are not. The sponsoring family member has to help them find accommodation, furnish the house, connect them with English language courses, Work and Income and, if needed, specialist mental health services.

Amanda Calder says it places a strain on all the families who arrive under the Refugee Family Support Category, “The current housing shortage is particularly hard for refugees searching for a rental property – they simply can’t afford the high rents and struggle to find a place to call home.”

New Zealand Red Cross has been running a successful pilot volunteer scheme for reunified families in Wellington, but it may not be continued unless extra resourcing is found.

It is estimated the government will spend just over $35 million on refugee resettlement by the end of the financial year, though that figure includes selection and processing and costs associated with Mangere Resettlement Centre which has been undergoing upgrades.

The Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment declined to say exactly how much funding it gave Red Cross for refugee support services, citing “commercial sensitivity”, but the charity’s last annual report puts its spending on resettlement at $6.8 million, most from government.

A Red Cross spokesperson says that it’s enough for core funding, but public donations are still needed for extras such as school uniforms or buying household items for former refugees that they can’t source through donations. For the volunteer programme to be expanded to reunified families on a permanent basis and nationally, the charity would need further resources.

Community lawyer Megan Williams says there needs to be consideration given to how other support organisations are funded.

“It’s the agencies who are the most immediately affected that are considered [for funding]. The ones, like Red Cross, who do that initial resettlement work. But there’s so many agencies surrounding them, like us, and healthcare providers, and social support services, all those other agencies that will come under increased pressure, They’re not given much thought for increased funding.”

For work on refugee family reunification cases, Williams said the law centre is not even close to meeting demand from the community and has to seek private funding for what little it is able to do.

Even at Community Law Wellington and Hutt Valley, which is relatively well-resourced, they have 50 cases ongoing at any one time, a waitlist of about 20 cases, all managed by two staff members and some volunteers. Some community law centres aren’t able to do any work on family reunification because they don’t have the resources.

“If I could improve the system … the big thing I would want to say is legal aid being made available for this legal work. It’s a complete lottery for the kind of help you’ll get depending on where you live,” she says.

The sponsoring refugee, and community organisations, often end up picking up the bill for this work.

Calder started helping the Somali community with immigration cases more than 20 years ago, but soon realised it wasn’t enough to give advice.

“I could never say to a refugee, good news, your family can come, but you’ve got to find $16,000 for airfares for six people to come here. I would always find the money, and I did it informally for a few years, approaching people who would gift the money.”

Calder set Refugee Family Reunification Trust up as a charity in 2001, and since then has been able to raise more than $1.6 million to help families with the costs of reunifying in New Zealand.

“Many refugees can’t access the immigration process because of their poor English and because it’s complicated, and they also can’t come up with the money. ”

The Greens’ planned review of refugee family reunification is yet to take shape but Gharaman says it is hoped it will look at everything from how family is defined to funding available to support family reunification.

Better family reunification processes would boost resettlement, says Ghahraman.

“For example, you might bring someone who can help with childcare because in some cultures – including our own – it’s how people manage young kids.

“That means adults can enter the workforce more easily and become contributing members of our economy.

“[Family reunification] is really positive in terms of morale and the humanitarian effort, but also the bottom line stuff.”

It’s part of our obligation to refugee resettlement to have good family reunification policies and process, she says.

There is no timeline set for the review yet, but Ghahraman says she hopes it will include consultation with the sector to work out what needs to change.

There are different opinions about what the best solutions are.

If Amanda Calder had her way, some of the quota places – set to double in the next three years – would be going to family members of UNHCR-verified refugees in the first place.

New Zealand takes the cases that UNHCR recommends, which are usually the most urgent, at risk cases. Calder suggests there’s an argument to take more family cases within this quota.

“There’s always that tension. Do you take a really urgent, at risk case, or do you take the family members of a person who has been here for ten years, and may not be as urgent, but who have been in a refugee camp for 20 years?

“It’s in New Zealand’s interests for refugee families to be together – it must save on mental health costs, it must save on so many levels, it’s better for refugees’ resettlement to have their family with them.”

Kidd agrees there needs to be better support for family reunification but that the quota should still be made up of the most vulnerable people.

Instead the number of places available to family members should be increased from 300 to 500 through the Refugee Family Support Category, and settlement support for them on arrival should be funded.

“Those people really need to be getting the same sort of support that quota refugees are getting. They’re coming from similar situations, even worse situations, and being seen upfront is really helpful to make sure they can get on to a level playing field and get good support.”

Christalin Thangpawl, chair of the NZ Myanmar Ethnics Council, says she hopes that the government does something to speed up the time it takes and make it easier to reunite refugee families in New Zealand.

“It’s possible. We’re all human beings, and it’s possible, because policy is made by human beings. It doesn’t matter what your religion, or your skin colour, or which language you speak, we’re all human beings who should be with family, and be able to reunify with a family member.”

*Mohamed asked that his surname not be used for personal safety reasons