Christian Religious Instruction is given in around 40 percent of New Zealand primary schools – not as an optional class, but one which parents must opt out of. Most of us believe in the separation of church and state, writes Tina Carlson, so why do we continue to give Christianity such prominence within our schools?

We are lucky to live near a local school which has a really good reputation, but I’m not sure if I will enrol my children there. Why? Because the local Brethren church is providing the school with weekly Religious Instruction (RI). I know ‘The Brethren’ has negative connotations, and I don’t want to demonise them in particular, but their presence makes me very uncomfortable – if I’m honest, it makes me angry.

That they are an evangelical/fundamentalist church is part of my uneasiness, yes, but denomination notwithstanding I don’t think it’s right to give any religious group access to primary school children, especially without parental consent. People have a choice about attending church and if that is what people want to do I respect that, but when it’s the church which is ‘attending’ the school, it impinges on my family’s choice to not participate in religion. That’s when it becomes problematic.

It came as a shock to me when I first learnt that in New Zealand many state schools do not teach about the world religions at all, supposedly because it is too contentious. On the other hand, around 40 percent of primary schools do provide scripture classes (and these are not seen as contentious?), which to confuse matters is sometimes referred to as religious education. I can’t quite get my head around this because in Sweden, where I come from, we have religious education as a core part of the curriculum – meaning that you learn about the world religions in a general, non-biased way. But Bible classes in public schools are viewed as something rather old fashioned, from the time before colour TV, and were done away with permanently in the 1960s. It is not just Sweden by the way: the way New Zealand handles religion in public schools is unusual, especially for a secular state.

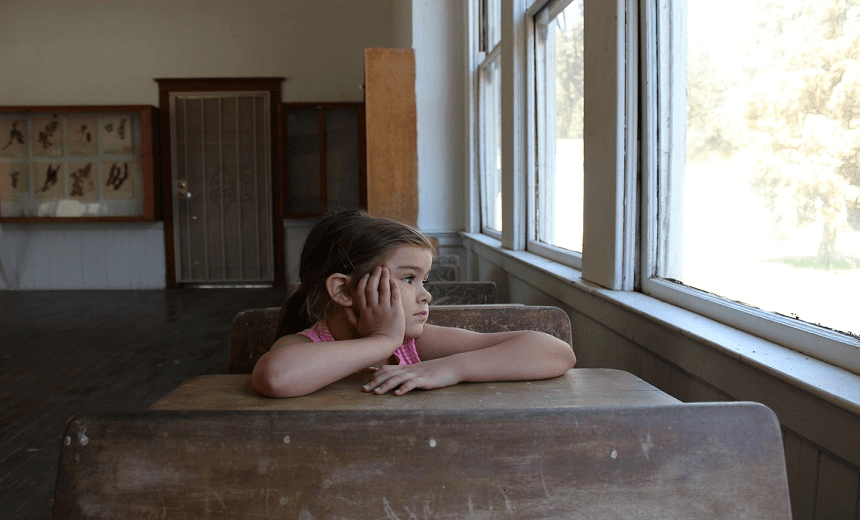

In schools where it is practised, Christian Religious Instruction (RI) is an opt-out system. The result is that children are segregated based on their – or rather their parents’ – religious belief. Separating children along these lines focuses on what divides us, not what brings us together; a school should be an inclusive place for all the children regardless of their race, gender or religion.

Because of religious segregation, my child will likely be treated as an outsider in her own school. These days many Religious Instruction programmes are run like stage shows: there is singing, dancing, games, lollies and cartoons, and any child who doesn’t attend would definitely feel that they are missing out. The programmes are targeted at very young children, usually starting between the ages of five and seven. How can these children be expected to understand why they are excluded?

While I would prefer that Religious Instruction be removed from schools, at the very least it should require informed consent. The right to opt out means that children attend Bible class by default, and tacit agreement is assumed. Speaking up against a school-endorsed programme is not something every parent is prepared to do. When a rapidly increasing 42 percent of the population now identify as non-religious, assuming Christian religious belief is simply not good enough. And another problem: if you don’t know about it, you can’t opt out. There are cases of parents not being told about Religious Instruction classes because they are marketed instead as Values Classes, without acknowledging that they are Bible-based.

The Churches Education Commission (CEC) – the main provider of Religious Instruction, which they call Christian Religious Education – claim that their classes are suitable for non-religious students and that they support the New Zealand curriculum. However when Victoria University religious studies professor Paul Morris reviewed their courses he said they were “not suitable for non-Christian, non-evangelical students” and may well be at odds with the curriculum. In the past the CEC claimed that their courses were endorsed by the Ministry of Education and the Trustees Association, but stopped after being censured by the Advertising Standards Complaints Board. The truth is that the CEC is entirely self regulating and that they themselves are the only ones that approve the content of their courses. They do not have any official authority and have nothing to do with the Ministry of Education.

The piece of legislation that allows Religious Instruction to take place in state primary schools is the Education Act 1964. In fact this is all the Act does – of the 204 original sections, only five remain and they all relate to the practice of Religious Instruction in state schools. Other notable sections of the Act dealt with things like ‘Married Women as Teachers’ and other such societal conundrums. That section has of course since been repealed, but it gives a flavour of the times in which the Act was written. One of the problems with the Education Act 1964 is that it is predates current human rights legislation by around 30 years, so it can therefore not be assumed to comply with it.

The Ministry of Education (MoE) does not collect any information about which schools provide Religious Instruction, much less what material they use, nor are they particularly interested. This is because the school is technically closed when RI takes place. That the closure is in name only and that RI takes place during the school day – so the school does not appear closed to children or parents – does not matter. When parents complain about RI to the MoE they are simply referred back to their school board or to the Human Rights Commission.

This is not to say that the MoE is unaware of the problems within the Education Act 1964. It was advised 16 years ago by its own lawyers that the opt-out system constitutes direct discrimination. There were also guidelines prepared in 2006 to assist school boards in relation to Religious Instruction which would have gone some way to moderate current practices, but these were never released.

But it is not just non-religious parents and their own legal advice that the MoE is ignoring. In 2015 the Trustees Association (NZSTA) recommended that the Religious Instruction provisions be updated, for reasons including that they are “ineffective, outdated and an ongoing source of friction” [PDF]. Just recently the Human Rights Commission (HRC) said that an opportunity to review the religious instruction provisions, “an issue of some contention”, had been missed under the Education Update Bill of 2016 [PDF]. Why the MoE chooses not to act on all this information is anyone’s guess, yet they are adamant that the Education Act 1964 will not be reviewed.

Which brings us to the Human Rights Commission itself. The Commission has been remarkably quiet on this issue, at least publicly. The HRC will refer you to a little booklet called Religion in New Zealand Schools: Questions and Concerns [PDF], authored by the above-mentioned Professor Paul Morris. The guide is overwhelmingly positive about Religious Education, or learning about religions and the beliefs of others. But when it comes to Religious Instruction and the observances of a particular religion, the message is ‘it’s complicated’.

The HRC guide specifically highlights that the issue has not yet been decided in a New Zealand court of law. The complication arises because under the current legal provisions Religious Instruction is allowed in a secular school, providing you do not discriminate. According to the Bill of Rights discrimination occurs if someone is treated differently and disadvantaged. So does Religious Instruction constitute discrimination? Well, it depends on how it is done. But if only one option is provided, and that is the most common practice in state schools, aren’t those for whom that choice is not applicable ‘treated differently and disadvantaged’? Imagine if the Education Act 1964 allowed Political Instruction instead of Religious Instruction and schools then decided to allow only one political party to attend, to spread their ideology unchallenged on a weekly basis. Would that be fair? Would it be reasonable?

The Secular Education Network (SEN) is a group of parents and individuals, of which I am one, who believe that the Christian prominence and bias in public education is inherently unfair. We believe in the separation of church and state and that all faiths should be treated equally. We want fairness for children of all faiths and beliefs in an inclusive curriculum with non-biased teachings about religions and values. The SEN is seeking to challenge what we believe is the systemic religious discrimination in New Zealand state schools. We have recently taken a legal challenge to the Human Rights Review Tribunal and are hoping for a ruling in the High Court. You can contribute to this challenge through the Givealittle page here. The Secular Education Network is also a community for parents who are thinking of opting out, are unsure about their rights, or want to encourage their schools to change Religious Instruction practices, as well as a place to share information and support others in the same boat. It often helps knowing that you are not alone.

I believe it is time that some more voices are heard. It is time to halt the Christian monologue and open up an inter-faith dialogue which is inclusive of the non-religious. Our children need to have access to quality education about the world religions, beliefs and practices, because without knowledge there can be no understanding, and without understanding there can not be tolerance. My argument is for the right to religious freedom, and included in that is the respect of each other’s beliefs. I hope that is something we can all agree on, non-religious and religious alike.

Tina Carlson is a Playcentre mum. She has a Bachelor of Arts with a sociology major and is a qualified electrician. She lives on a lifestyle block with her two daughters and husband.

Follow the Spinoff Parents on Facebook and Twitter.

[contact-form-7 id=”249″ title=”Flick Connect Form”]