When life goes completely online, what happens to our performing arts that require face-to-face time? For Taranaki kapa haka group Aotea Utanganui, it meant adapting every part of how they practiced.

In mid-April, the kapa from Te Kāhui Maunga, the regional area which encompasses the traditional waka boundaries of Aotea, Kurahaupo and Tokomaru, welcomed the mauri of Te Matatini to the rohe, completing the first of many steps in their role as hosts of Te Matatini 2025.

“He kitenga kanohi, he hokinga mahara” – a familiar face stirs many memories. The pōwhiri for the mauri of Te Matatini was surely that. While a time of celebration, it was also a time of reflection. Kapa haka in Te Kāhui Maunga have faced many challenges over the last few years. None more significant than Covid, which caused the cancellation of the most recent regional whakataetae in 2020 with only three days’ notice.

Janine Maruera, one of the leaders of Aotea Utanganui, a kapa from the Te Kāhui Maunga, recalls this experience as an extremely difficult for all the teams and organisers involved. “There was a lot of debate and discussion before the decision was made. It was devastating for a lot of kaihaka who had put in months of training.” For the Pātea Māori Club, a kapa Maruera also leads and many of Aotea Utanganui also belong to, “things came to an absolute halt.”

Following the cancellation of the regional whakataetae, the national competition was then delayed from 2021 to 2023. Aotea Utanganui tried their best to move te ao haka online in the meantime, but with the stresses of Covid – including the loss of both of their leader’s fathers during the lockdowns – the stress proved too much.

“We tried some Zoom practices. They were difficult but hilarious at the same time,” Maruera says. “They became instead more of a chance for us just to stay connected. Ultimately, we came to the conclusion that the best thing for each of us to do was to put kapa haka on the back burner and focus on our own whānau and hauora. This was good for everyone as the weight was taken off our shoulders. It meant that when we were able to start practising again, everyone was in a good place. Tika ana te whakataukī, ka pai ki muri, ka pai ki mua. If everything goes well behind the scenes, at home; all will be well at the front, at kapa wānanga.”

As outlined in the Embracing Digital Transformation report by Toi Mai, which explored the ways five different sectors applied new digital delivery models due to the pandemic, experiences like Aotea Utanganui’s were common among those in the kapa haka space. “While technical difficulties abounded, including wi-fi connection, device availability, some without technical skills, internet lag and music issues, the most significant impact was the loss of wairua in rehearsal and whakawhanaungatanga,” the report said. And so, the first forays for many into that online space were about whanaungatanga, the priority being the health and well-being of whānau.

While this competitive kapa haka faced meaningful challenges moving online given the level of coordination and precision required for the stage, less competitive initiatives in Taranaki found success such as Kapa ‘aka with Whaea Shay, a kaupapa led by Ngāti Ruanui, a local iwi, which focused on teaching waiata and poi over Zoom.

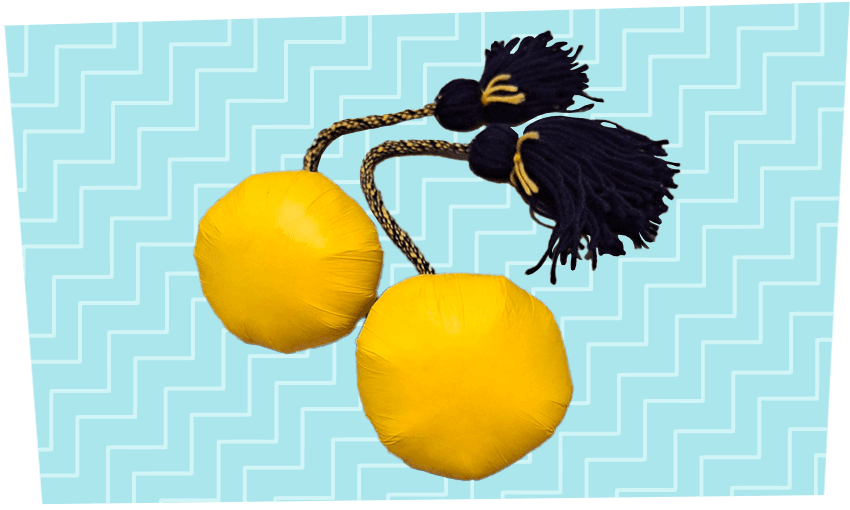

Aotea Utanganui’s change of approach proved successful, giving the kaitito of the kapa time to compose new waiata and think deeply about what messages they wanted to bring to the stage. For many rōpū, the online mahi didn’t look the same as when they could gather in person, but it was still an important time to build relationships and start to craft the many foundational parts of the performance that don’t rely on harmonies and timings. The fruits of this labour were seen throughout Aotea Utanganui’s performance at Matatini, but perhaps most of all in their whakawātea which featured samples of waiata from the Pātea Māori Club – including Poi E.

“It had been 18 years since Aotea Utanganui had been on the Matatini stage. The whole wheako was humbling, an honour and massively awesome,” Maruera says. “We had an amazing experience in the lead-up and at the whakataetae itself. We felt that we were taking really good stories to the stage and were excited about representing all of our people at home and past members who we have lost.”

Aotea Utanganui did not make the finals, but to get as far as the Matatini stage following years of unprecedented disruption was a testament to the commitment of the rōpū and their passion for the art.

Aotea Utanganui represents over 50 years of competitive kapa haka in South Taranaki. The first competitive kapa from the area, the South Taranaki Māori Club (a group that would later become the Pātea Māori Club) performed in what was then called the New Zealand Polynesian Festival, later Te Matatini, in 1972. So for the current rōpū, making a strong comeback after the years of cancellations was the only option to uphold the standard that had been set for generations.

“We continue to put our energies into this group because both my husband [Andy Maruera, another leader of Aotea Utanganui] and I wouldn’t be where we are if it wasn’t for this group and the Pātea Māori Club,” Maruera says.

The Toi Mai report noted that many kaihaka didn’t think full scale kapa haka practices were feasible online, and cited issues with connectivity as a barrier to online training in this space. “The difficulty with online training is you aren’t able to really experience the person and how the wairua of that person is,” said one respondent.

Another cited the cultural challenges with putting certain content online, regarding the rights to this content – an issue that is prevalent in Māori culture. “When you are sharing it with the wider world and unfortunately, some people want to mistreat or diminish the mana of our culture or our waiata into re-editing or augmenting or having a tutu with those taonga and so, there is a risk,” they said.

But Maruera says while these challenges put a dampener on things during the pandemic, once people were able to train in person again, it was like no time had passed – that passion for performance remained.

“For us, there is no better way to express what being Maori is than through performance. Now, our own tamariki are coming through the ranks and loving everything that kapa haka has to offer: whanaungatanga, discipline, mātauranga Māori, te reo Māori, and the list goes on. Personally, [our] greatest victory was performing at Te Matatini with lots of people who are new to haka and of course, our tamariki.”

With so many tamariki coming through, it remains to be seen how this generation who have been raised in the digital world will carve out the place of these new technologies in te ao haka.