The Master of Technological Futures is designed to allow students to adapt to the demands of a rapidly changing world, at any stage of their career. Amanda Peart spoke to graduates and staff about how it’s transforming the future.

Working as a GP in inner-city Auckland, Dr Reza Jarral could see first-hand the lack of equity in the health system. He observed how the conventional delivery of its services was preventing people accessing the help they needed. The way he had to treat patients felt slow and inefficient. He knew he could see more people and provide better treatment if he had the right technology; technology he knew existed, but he just didn’t know how to harness it yet.

“I wanted to prove to myself that I had more to offer and that I could find new and better ways of advocating for my patients than just treating one patient at a time in a clinic,” he says.

At Tech Futures Lab, the future focused tertiary education organisation established by Frances Valintine in 2016, Jarral found the knowledge, confidence and connections to turn his vision into real value for patients. He discovered the ethical use of scalable technology (such as Artificial Intelligence) was key in his goal to democratise healthcare. This might allow people to access a doctor as quickly and as easily as they can order a pizza; ensuring healthcare can be delivered to the most vulnerable, but in a way that keeps their data secure, and private.

He is now a graduate of their flagship degree, the Master of Technological Futures, and continuing on his quest to bring healthcare to everyone, as the clinical director for the virtual GP app CareHQ. He’s also part of an international multidisciplinary project with the World Health Organisation, developing tools that benchmark safety metrics for health AI.

“The degree equipped me with the skills and exploratory opportunities I needed, and opened my eyes to possibilities that I wasn’t aware of before, and it is still resonating with me today,” says Jarral.

The Master’s degree is project-based, practical, and focused on giving students the knowledge, the tools and the connections to succeed in the world outside the classroom, as it is now, and how it might be in the future. It arms students with the critical thinking skills and tangible project experience to stay relevant and thrive in the face of inevitable change. Master’s projects should use what TFL calls “emerging disruptive technologies”, such as AI, machine learning, blockchain, as well as non-digital tech, like human-centred design, to solve a problem, or seize an opportunity.

Jarral’s project was “themed around the ethical application of AI in health, and in what ways we can contribute to this seemingly vast, intersectional and complex problem space”.

His sub-projects as part of the programme included co-founding a social impact platform with a data scientist, that scraped geotagged metadata from the internet to predict infectious diseases ahead of the curve. As Covid-19 emerged soon after they started their work in November 2019, the concept gained traction and received a grant from The Rockefeller Foundation, New York. He was also awarded the Acumen Generosity Award as part of an online student accelerator, with his work published in the British Medical Journal, to encourage others to tackle the problem area.

Jarral has also worked with an international standards body to publish the P7010 – a tool to help organisations monitor and measure the impact of AI systems on human well-being. The diversity of his practical work was possible because of the supportive, creative environment of the masters course.

“For anyone who feels like their career has pigeon-holed them in, and they want to break out and do new things, the ‘smorgasbord’ type approach in the Master’s degree is a fantastic way of trying new things and being exposed to new perspectives and a diverse group of people, without any risk. You’re in a safe environment and very well supported in your learning,” he says.

Jarral has long been guided by the Japanese philosophy of ikigai – a concept that captures your reason for being. It’s often explained in familiar western terms as the venn diagram where there’s an intersection between what you’re good at, what the world needs, what you love doing and what you can be paid for.

“If you can try and narrow down something that falls within those four sectors, you can have a sense of wellbeing and purpose that you didn’t have before,” he says.

“Throughout my Master’s I was always re-evaluating my ikigai based on the new information I was getting and new things I was learning, and as I kept narrowing it down, a career came out of it that I could not have imagined at all.”

Tech Futures Lab is a companion organisation to the Mind Lab which was founded by Valintine in 2013 to provide its students with a skill set designed to help them adapt to the demands of the future. The Master of Technological Futures is the only degree of its kind in New Zealand. It offers a 12 or 18-month Master’s degree, with an online only option for those who need it. It is designed to inspire people to refocus or future-proof their career, try new things or scale existing ones, or guide graduates onto a completely new career path.

Expert advisors support students on their projects and a rotating roster of industry experts who live and breathe the latest tech, including Valintine, are session speakers and lecturers, exposing the students to the latest industry news and innovations from New Zealand and around the world – looking at the macro and the micro. It’s also possible to study while continuing to work, and this allows students to have an immediate impact as they learn. Advancements in tech that happen one day can be the subject of a lecture the next, with the knowledge making an impact on how the students does their job.

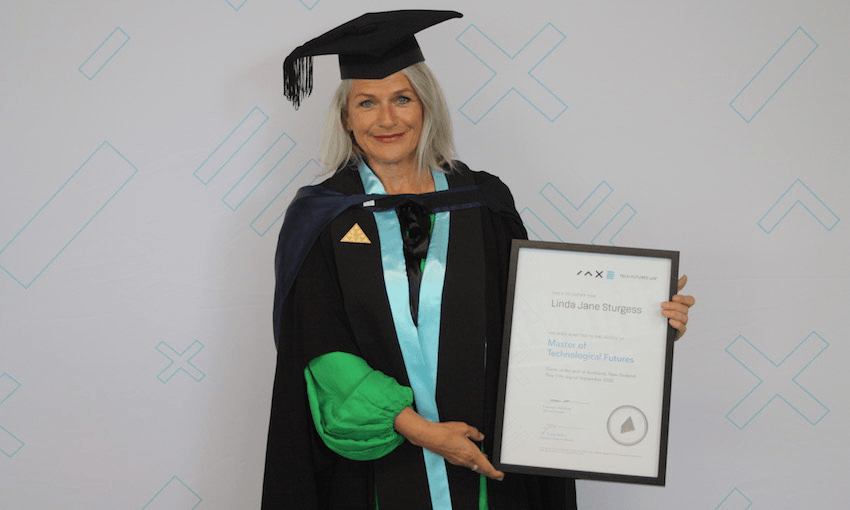

For top banking professional Linda Sturgess, the master’s degree was her way out of a career rut, and into a new, more fulfilling role at BNZ, managing a team of business bankers, who are funding and supporting innovative companies.

“I had been dealing with personal wealth for 11 years and felt painted into a corner in my career. I felt like I needed something new to reinvent myself,” she says.

Her manager suggested the Master of Technological Futures, and she was hooked from the first information evening. Sturgess was there to kickstart her next career move, but she also found a new outlook on life, through the “transformational” degree. She even swapped her SUV for the bus after being inspired by the focus on sustainable futures in the degree.

“It reignited that passion to find out and be curious and not take things as they are just because that’s the way they’ve always been done,” she says.

Through her career helping people manage their money, Sturgess could see the disparity between who was able to access financial advice and assistance, and who really needed it. She wanted to make good financial advice accessible to the younger generation and her master’s project focused on designing a platform for millennials to access digital financial advice and take action to meet their financial goals.

“It made you think so much deeper about some things, and challenge your old values and thought processes. I was worried I was going to be the oldest there by 30 years, but that wasn’t the case at all and would not have mattered anyway. The masters was full of amazing people; it sparked a real curiosity and a desire to be the absolute best version of myself.”

Kaupapa Māori values are embedded in the degree, emphasising the need to look at things in terms of intergenerational benefit rather than short-term gain, learning from the past, caring for our environment. The projects are informed by manaakitanga and their potential to benefit Aotearoa exploring things like improving equity and outcomes in housing, health, employment and education.

The course challenges the students to imagine what their vision of Aotearoa in the future could be. What would our key sectors be, if not primary? How can we return our environment to pristine condition and put climate change at the heart of our decision making? What do we need to do to make sure our kids are educated in the way that is needed in the current world? The answers to these questions are informed by indigenous knowledge.

A key guide to these values at Tech Futures Lab is Pou Awhina/Māori Advisor, Sara Stratton, who is herself a graduate of the Masters in Technological Futures. Stratton (Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Kahu) guides students and staff on tikanga, Māori methodology and the Te Tiriti o Waitangi, acting as a bridge between Māori and Pākehā cultures, mindsets, and values.

Stratton master’s project was called A Māori Lens on Digital Technology, with a particular interest in ethics and values, and what a Māori perspective of values would bring to the rapidly evolving sector. She is a firm believer that Māori and indigenous values and knowledge are desperately needed and a unique guide on the journey on the path to new horizons. Since graduating, she has become a member of the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on AI Fairness. She is also part of a project to develop a basic digital technology introduction programme for women in prison, 64% of whom are Māori, to empower them with new skills and better prepare them for the future.

What Stratton found at Tech Futures Lab was a genuinely different and truly relevant way to learn and a place where her voice and perspective were harnessed as part of her learning. It wasn’t easy and was often uncomfortable. Leaning into that discomfort was essential “as you know that’s when change is really happening,” she says.

When Frances Valintine registered Tech Futures Lab she was studying at the Singularity University in Silicon Valley, an experience that exposed her to a level of conversation on complex and long term themes that she felt were not being explored in New Zealand.

Her vision was for graduate school where “people come together to have complex conversations across a wide range of areas which have some intersectionality between them, or conversions between them and were common to everyone who was in business, based on the five pillars of people, planet, processes, technology and data.”

She is a self-confessed learning addict; however, not enough people are taking up the chance to get their own fix, she says, with fewer adults pursuing learning opportunities. The underinvestment in professional development means people are missing out on something that could transform their career, their community and themselves, and businesses are missing out on valuable skills and knowledge coming back into their organisation.

“Adults can constantly learn and do new things, and they’re not going to get what they need, to continue their career, in their day job,” she says.

“Learning and developing talent is a core part of hiring staff, whether they do six weeks or six months. If you’re not investing in people to learn and evolve, then you’re not getting the benefit of all the capabilities they have.”

Valintine has watched as Covid-19 has forced businesses to rethink the skillsets they really need. She’s also seen the labour market evolve under the pressure of the pandemic, and now New Zealanders may be competing with international talent for jobs, due to the potential of remote working. It means staying aware of how technology is changing the way we work and upskilling is vital.

“It’s my fear that professionals get to a certain age and then lose their confidence in what they can do, because the language around them is changing and the skillsets are changing, and they are sitting there saying ‘what just happened?’” because they’ve left their career development to chance,” she says.

The Master of Technological Futures is designed to take that chance away, and release the potential of learners at any point in their careers.

“Do it for yourself, reward yourself, so that you can feel confident, you feel alive with a sense of responsibility, accountability, and this desire to understand what good looks like.”