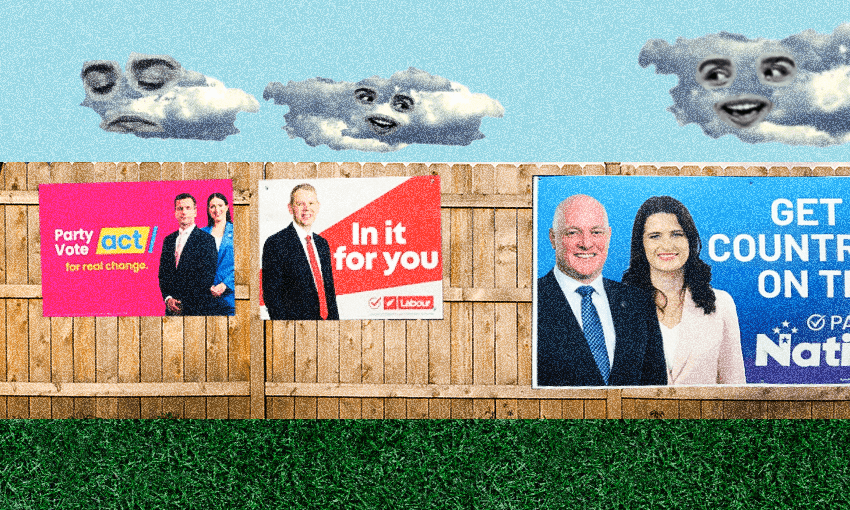

Across the country, an election brings political advertising affixed to the front fences of houses – some hosting an eyebrow-raising array of clashing parties. So who are the people behind these eclectic displays?

Just as fairy lights on houses and advent calendars at the supermarket herald the advent of Christmas, the emergence of multihued election signs featuring the faces of grinning candidates ushers in a different kind of season: election time.

Among those who display these ads in their front yards or on their fences, the norm is that they reflect a household endorsement for a particular political party or candidate, and an encouragement that others make the same choice on election day.

But there is also a more chaotic kind of display, assemblages of parties on the left, right and beyond, all stuck to a single politically confused fence. So what’s behind these nonpartisan curiosities of election campaign signage? Are the people who say yes to all these signs especially agreeable types, confused swing voters, politically naive, extreme centrists, champions of the democratic process, or avid collectors excitedly hoarding hoardings? Do they even care who wins?

Trading a bit of fence space for cold, hard cash would be an easy explanation for disregarding one’s political preferences, but that’s (hopefully) not the case, as it’s illegal. The Electoral Act 1993 states that it’s against the law for payment to be made in return for the use of any house, land, building or premises for campaign hoardings. There is a loophole, though, if “it is the ordinary business of an elector to exhibit for payment posters and advertisements and the payment or contract is made in the ordinary course of that business”.

In Pio Faamausili’s manicured back garden in the Auckland electorate of Mount Roskill, there are plots teeming with spring onions, taro, cabbages, newly planted strawberries, and the healthiest-looking silverbeet you’ve ever seen, but on the front lawn two political hoardings stand side by side: one imploring passers-by to vote for the local National candidate Carlos Cheung, the other to vote for the local Labour candidate Michael Wood. If the messaging seems mixed, it’s on purpose.

At 69, Faamausili is retired, but this week will be returning to work for 11pm-7am shifts as a forklift driver. Intriguingly, the National and Labour signs on his front lawn are not an endorsement of either. Faamausili, who has voted Labour for more than four decades, says he’s become equally disenchanted by the major parties – and politics in general – and sees the hoardings as a kind of unique political statement that he’ll be keeping an eye on both parties in the lead-up to election day. “I’m gonna watch these two and the way they yappity yap in the debates,” he says, pointing to the pair of two-dimensional politicians on his lawn.

He wouldn’t turn down other candidates, either. “If someone comes and they want to put a sign up, I’m gonna let them because I want to find out more about them,” he says. Later in the conversation he adds a very specific caveat: this invitation doesn’t extend to Winston Peters.

For others, accommodating these various signs on their fence is motivated by a sense of egalitarianism. At a west Auckland property on the corner of a busy intersection – prime real estate for those running a political campaign – there are no fewer than five different political parties plastered to the fence. There’s the ubiquitous Labour and National placards, interspersed by smaller parties Act, NZ First and DemocracyNZ. In a brief exchange at the front door, the occupant responds to my question about why they have so many diverging political parties on their fence with a confused laugh and a very straightforward answer: “They ask and we say yes.” After all, “they need to get their message out there somehow.”

Similarly affable is Sam, the occupant of a house with a duet of National and Labour campaign signs pinned to its fence in central Auckland. Sam’s is a Labour-voting family, but when National showed up first asking to attach their sign to the fence, they agreed – as long as they promised to “leave space for Labour as well”, says Sam. “We just thought we would give a chance to both parties to share their stuff for the election.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, accommodating two opposing politicians on a single fence wasn’t without drama. “Labour came and were like, ‘oh, there’s no more space on the fence’ – apparently National covered up the whole fence,” says Sam. “So we had to call up National to come take one of their boards off so Labour could put up one of theirs.”

Just down the road, I talk to Jamuna, who has the faces of three different political party leaders on her fence. “They come to the door and ask us or ring us and we just say, ‘yes, you can go ahead,’” she says, looking slightly perplexed as to why anyone would even be fazed by the variety. “It’s just to please them – it’s on the corner and people can see it so it’s just to give them the opportunity to display things.”

Despite being a typical swing voter, noting that she’s changed her vote every election, Jamuna has already made her decision about where her two ticks will go this election. When I ask her why she wouldn’t prefer to reserve her fence space solely for the political parties she actually wants to form a government, she’s ambivalent. “People are going to vote for what they want, so what does it matter? It’s just about giving them a chance.”