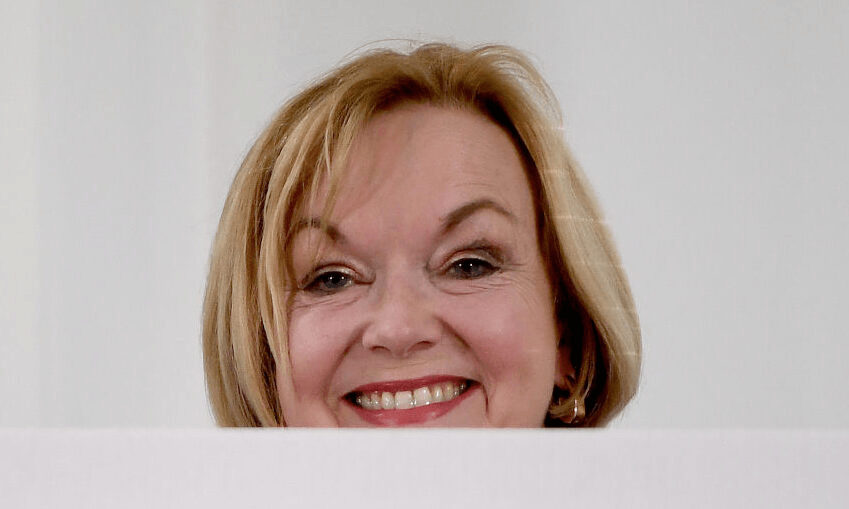

The path might be steep and unsteady, but there is a path to victory that could see Judith Collins sworn in as prime minister after October 17. Toby Manhire crunches the numbers.

To be clear: with 12 days to go the National Party remains very much the underdog. Several polls in recent months have put Labour not just heading for victory, but capable of governing as a single-party majority government – something that has not been delivered since MMP was introduced in 1996.

National would need a lot of things to go right to defy the odds. It’s far from in their control. But they’re still in it. Let’s take a look at the party’s likeliest path to government – one which doesn’t require support for any party to move up or down by more than a few points.

National + Act

Pending some unimaginable upheaval, National’s path to government will need the support of Act. The free-market, free-speech, anti-gun-reform party has soaked up a good number of disaffected National voters and surged to the brink of its best election result ever. Any National-led government will have Act as coalition partner or confidence and supply ally.

Keep the momentum and mop up the minnows

Ever since the first leaders’ debate, Judith Collins has taken on a new lease of leadership. The confidence appears to be translating into improved polling, with the soothing performances of Shane Reti making up for the holes in Paul Goldsmith’s bucket.

Recent days have seen Judith Collins making an unmistakable play for votes from people who might have gravitated towards other smaller parties. A sudden run of references to her Christian faith, and a visit to an Anglican church, look like a medium-term play to solidify support in caucus, but also an invitation back to the mothership to the 1.4% of the electorate planning to vote New Conservative, according to the last Colmar Brunton / TVNZ poll. There have also been policy embraces of the racing industry – hello the remaining NZ First loyalists (1.4%)! Pronouncements on gun reform in the second debate round off a busy time of pitching the big tent on the right.

Labour voter complacency

The strength of Labour’s polling – over 50% a number of times – combined with the sometimes slapstick scenes that have bedevilled National in 2020 could see the turnout for the incumbents slip. There’s nothing National can really do to influence that, though, and they certainly won’t be relying on it happening.

The ‘shy Tory’ effect

The so-called “shy Tory” factor was coined to describe a phenomenon in which the Conservative Party of the UK outperforms its polling numbers. The theory goes that people are reluctant to voice their position to the pollsters, but once in the booth vote for a tax cut or toughness in law and order. Conceivably, this might be more pronounced under a more rightwing leader such as Judith Collins than you’d see under, say, John Key. Again, however, this is the last thing National would be wanting to depend on.

Half the house doesn’t need half the votes

Last week’s Colmar Brunton poll had National on 33% and Act on 8%. Together, the two parties were up three points from a week earlier. Labour was on 47% and the Greens on 7%, respectively down and up one point, so unchanged when stuck together.

The parties of the right are inching up, then, but with voting already under way, a combined 50% of the vote looks like fantasyland. The good news is they don’t need 50%.

The votes for any party that falls under the 5% threshold and fails to win a constituency go into a basket that is often labelled “wasted vote”. A better name might be “unrepresented vote”. Let’s say that the unrepresented vote amounts to 5% – as it roughly did at the last election. That would leave 95% represented vote, and so to command a majority in parliament, or 61 of the 120 seats, you’d need more than half of that 95%: anything more than 47.5%.

(It might be a bit different if there were an “overhang”, triggered by a party winning more constituency seats than the proportion they’d be entitled to under their party vote, but let’s leave that to one side for now.)

On current polling, the probability is there will be a low number of parties going to parliament: just four. But what if it was only three?

A Green wipe-out

National’s best path to victory would see the Greens fall under 5%. Across six Colmar Brunton polls this year the party has averaged 5.6%. The most recent result – 7% – will have sent waves of relief through the party, but it’s not quite banked yet. The Greens’ final results have tended to be slightly below their poll numbers, and there have been some suggestions that the Covid election might mean a dip in overseas voting turnout, where the Greens have traditionally performed disproportionately well.

For National, it’s another area in which there are few tactics that could help them – a full-bore attack on the Greens would likely only embolden their cause. But were the Greens to dip under that 5%, and with Chlöe Swarbrick a very longshot in Auckland Central, the door would open further for a Collins win. Indeed, nothing would be sweeter for National prospects than a Green result of 4.95%.

To the numbers

With all of the above in mind, it seems to me the likeliest path to a National-led government would, in short, see:

- National continues to climb, up to over 37%.

- Labour accordingly drops a couple of points.

- Act holds steady at around 8%.

- Green Party falls under 5% and fails to win an electorate.

- No other party surpasses 5% or wins an electorate, but combined collect around 5% of the vote.

Let’s plug all that into the Electoral Commission’s handy MMP calculator.

Parliament would end up looking like this:

That would mean a deeply un-MMP-looking parliament of three parties; and those who insisted in 2017 that the biggest party should lead the government would be biting their tongues.

Is it likely? No. But it’s a long way from impossible.