From the ‘fart tax’ to this week’s new ‘driver’s tax’ – no matter who’s in power, it’s as certain as death and, well, taxes that the opposition will adopt this tried-and-true naming convention for any policy that might hit constituents in the back pocket.

Nobody likes paying tax, not really. Sure, you can objectively approve of higher or broader taxes from an economic or social perspective, but you’re still probably not jumping for joy about the less-money-in-your-bank-account thing.

It’s for this reason that political parties of all stripes have taken in recent years to throwing “tax” to criticise any policy that could potentially involve an increased cost for the average New Zealander. Considering the government we have now, it seems like this tactic may have worked – the National Party in opposition loved nothing more than to call things a tax.

During last year’s election campaign, National could hardly go a day without calling out Labour over its “ute tax” or accusing it of introducing a “capital gains tax by stealth”. And this very week, Labour has decided to jump on board, taking aim at National over its so-called “driver’s tax”, proving the “[blank] tax” attack line is totally bipartisan.

By definition, a tax is a universally applied fee added onto income or a service – so it’s not completely disingenuous for either party to have coined these new names. But it’s certainly a slight moulding of the truth given these supposed taxes don’t apply to everybody in the way that GST, for example, does.

And it’s not new in politics, either. There was the “fart tax” of the early noughties, for example, while National in 2020 launched an entire campaign around Labour’s supposed plans to introduce dozens of taxes. Some, like a “water tax”, I can’t really explain.

Here are some of the most memorable examples of a proposed government-imposed cost being labelled a “[blank] tax” as a political attack. This list will be updated as further cases come to hand, or if we can be bothered.

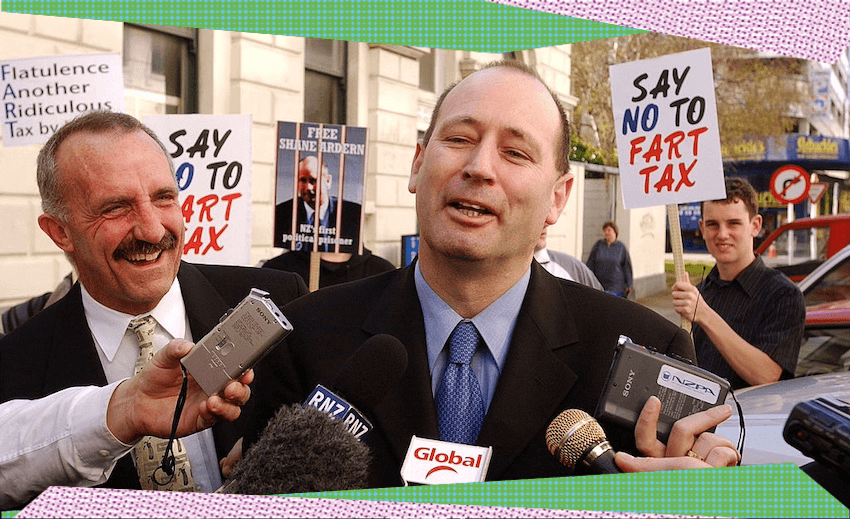

‘Fart tax’/‘burp tax’

An oldie but a goodie, and one that has continued to rear its head in the two decades since. The so-called fart tax of 2003 proved so controversial it has its own Wikipedia entry. It describes a proposed agriculture levy that would have been applied to livestock farmers (in effect to combat the, err, farts from cattle). The name was pretty silly given it was really the burps that should be targeted. Nevertheless, it was this proposal that prompted a National MP to drive a tractor onto the steps of parliament, a moment that has been immortalised in New Zealand political lore.

Skip forward into the 2020s, and plans to levy emissions from agriculture were back in the spotlight again as part of the Labour government’s He Waka Eke Noa scheme. The new coalition government has pushed the plan back five years to 2030.

The ‘ute tax’/‘car tax’

In reality, the now-scrapped “ute tax” was a reference to the Labour government’s clean car discount. That discount was paid for by levying an extra cost onto the price of newly imported combustion engine vehicles.

It was a constant target of attacks from National and Act, and one of the first things scrapped by the new government after last year’s election.

“The scheme was designed to achieve fiscal neutrality, with the ‘Ute Tax’ charges covering the rebates and administration costs. However, more was paid out in rebates than was received in charges, with taxpayers footing the bill,” said transport minister Simeon Brown earlier this year.

It dates back earlier than this, too. Here’s a National Party tweet from 2020 taking aim at the “car tax”.

National will repeal Labour’s Car Tax. pic.twitter.com/XperE38zke

— NZ National Party (@NZNationalParty) June 18, 2021

Since the subsidy was ditched, sales of electric vehicles have dropped dramatically.

The ‘app tax’

“App tax” was used by National as an attack line last year, and now it’s being used as an attack by Labour. That’s because while National campaigned on scrapping the addition of GST on services like Uber, it decided to keep it when entering government. “Obviously, we campaigned on a tax package that had other sources of revenue, and we now have a coalition government. We need to make adjustments,” finance minister Nicola Willis said.

Labour’s Grant Robertson, in response, said: “This is an absolute shambles, alongside putting in place tax cuts funded by more people smoking. We now have a backflip around this charge,” he said. If there’s a political attack more widely used than calling something a “tax”, it’s accusing your opponent of a flip-flop.

‘Capital gains tax by stealth’

The name given by Nicola Willis to the former government’s extensions to the brightline test. While the brightline test does act akin to a capital gains tax – by requiring income tax to be paid on capital gains from properties that aren’t the owner’s main home, if they’re sold within a certain timeframe – it is narrower than the full-blown CGT that was proposed by the Labour government’s tax working group.

“National will reverse Labour’s stealth capital gains tax by taking the brightline test back to two years and returning to the previous version of the rule, ensuring Kiwis’ family homes are protected from the tax,” said Willis in 2023. The change will be effective from July 1.

The ‘reverse Robin Hood tax’

So called because it involved taking money from the “poor” to subsidise the “rich”, this was another nickname given by National to the government’s clean car discount scheme. “In essence it is a reverse Robin Hood system, they are taking from the poor to give to the rich and that’s just not right,” former National transport spokesperson Michael Woodhouse said.

It’s certainly a lot catchier than the other entries on this list.

‘Jobs tax’

This was National’s name for the social insurance scheme proposed by Labour. In short, the scheme would offer ACC-like payments to people left out of work due to redundancy or illness, meaning they could maintain an income if they had been forced to stop working for a reason other than an injury.

In response, Christopher Luxon said: “Small businesses have been struggling just to keep the doors open over the last two years. Now, just when Kiwis deserve some relief, the government wants to hit workers and businesses with a brand new tax to fund a new gold-plated unemployment benefit,” Luxon said.

Regardless, the jobs insurance scheme was ditched (or, at least, indefinitely bumped down the road) in Chris Hipkins’ policy bonfire a year ago.

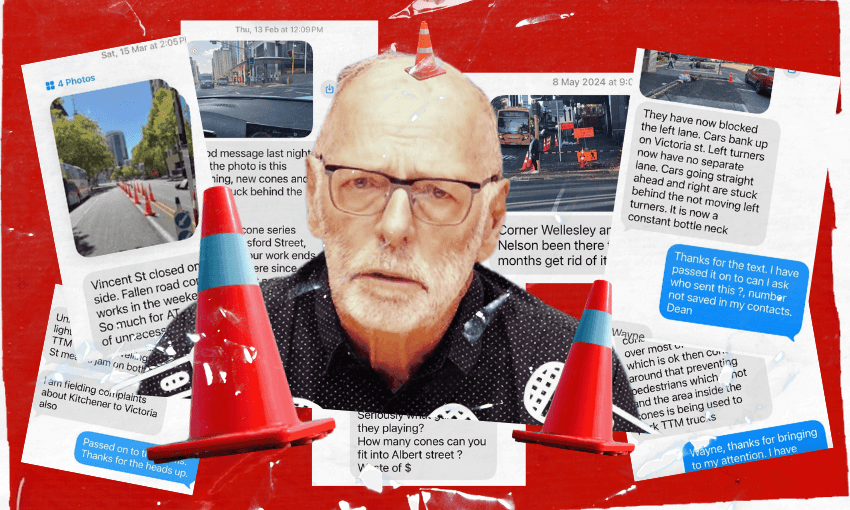

‘Driver’s tax’

The newest addition to this list. Announced this week as part of the government’s draft transport plan, it would see vehicle registration costs hiked by $50 from 2026. Labour was quick to describe the fee increase as “effectively taxing drivers“, with MP Shanan Halbert following the tried-and-true naming convention and labelling it a “driver’s tax”.

Aucklanders just got slaughtered by Simeon Brown- New ‘drivers tax’s’ and a axe to funding any infrastructure that provides any alternatives to driving. Show me a global city that is going backwards like this?!

— Shanan Halbert 🛥️ 🚊 🌍 🏳️🌈 (@shananhalbert) March 4, 2024