In the wake of a minister asking for an apology over a critical comment directed at her in te reo Māori in the debating chamber, Lyric Waiwiri-Smith explores parliament’s complex relationship with our indigenous language.

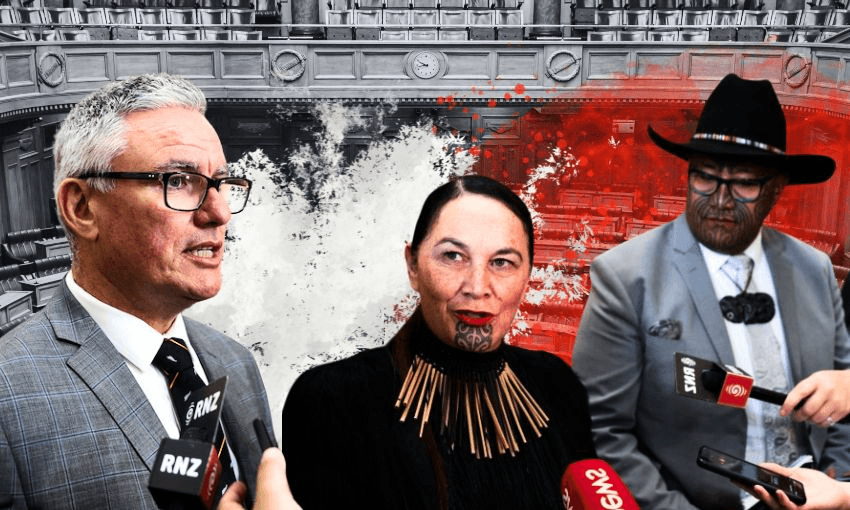

A comment made in te reo Māori to a government minister is still causing controversy, three months since it was uttered in the debating chamber. Children’s minister Karen Chhour has appeared teary-eyed in recent interviews, telling reporters she is under the pressure of a toxic working environment and feels victimised by other MPs, referencing a specific comment by Te Pāti Māori MP Mariameno Kapa-Kingi, who addressed her in te reo Māori in the House in early May: “E te minita, ka aroha ki a koe kua karetaohia e tō pāti. Kia kaha rā.” (Translated by Hansard: “To the minister, how sad that you have been made a puppet by your party. Be strong”.)

Chhour wasn’t aware of the meaning of the comment until Hansard was updated to include the English translation later. She complained to the speaker, who later told her that Kapa-Kingi would apologise. “I felt that that was wrong and she should apologise for that,” Chhour told RNZ. “Then [the speaker] said he had spoken to her, she was going to apologise to me … crickets, nothing.” Te Pāti Māori has denied Kapa-Kingi was asked to apologise.

MPs are able to listen to live translations of te reo Māori in parliament via an earpiece, but a brief comment in an otherwise mostly monolingual speech can be easy to miss. Many decades ago, Chhour may have had to wait much longer to hear or read the English translation of a Māori speech in parliament, and Kapa-Kingi may not have been allowed to deliver it at all. For more than 75 years, no Māori language interpreters were provided by parliament, and official te reo Māori translations were short lived. The practice of translating te reo Māori in parliament is much younger than the institution itself.

How long has te reo been spoken in NZ’s parliament?

Parliament saw its first Māori members sworn in 14 years after its establishment in 1854, when the Māori Representation Act 1867 created the first Māori seats – Northern, Western and Eastern seats in the North Island, and a Southern seat for the South. The seats were first held by Frederick Nene Russell (Northern), Mete Kingi Te Rangi Paetahi (Western), Tāreha Te Moananui (Eastern) and John Patterson (Southern). They were meant to exist only for five years, with the aim of giving representation to Māori excluded from parliament through land ownership requirements, but as issues with Māori land ownership continued the seats were made a permanent feature of parliament in 1876.

“Māori” wasn’t mentioned in parliamentary sessions until a year after parliament was established (“native” was a more common term used to describe tangata whenua instead), and the first full speech in te reo Māori was not spoken in the House of Representatives until 1868, when Te Moananui became the first Māori to speak in the chamber.

Translated by interpreter Edward Walter Puckey, Te Moananui told the House: “My thoughts and the thoughts of Māori people are not similar to the thoughts of the Europeans, they lie in a different direction … I say to you wise people, work: you the men whose thoughts are wisdom, work: you the people having understanding, do that which is good for the people, and lay down wise laws. Have no occasion to be anxious; you the people having wisdom should do all in your power to promote good.”

Attempts were made – and rejected – to establish a Māori iteration of the Hansard until 1881, when Western Māori representative Wiremu Te Wheoro proposed “speeches delivered by the Native members in the House be translated from Hansard, and printed for circulation among the Natives”. This saw the birth of Ngā Korero Paremete, the Māori-language Hansard which continued for 25 years until 1906, at which point it likely ceased as MPs were pressured to speak English and amid a wider suppression of te reo Māori, according to parliament’s official website.

Hang on – what is a Hansard?

That’s the official name for transcripts of parliamentary debates in the House of Representatives, which began in Aotearoa in 1867. (It’s named after Thomas Curson Hansard, the first official printer of the UK parliament in the early 19th century.) Parliament’s website publishes transcripts of every day the House sits and these are later bound into indexed volumes.

Anyway, back to what you were saying about interpreters …

They were present in the House from 1886 to 1920, after which point Māori MPs could only speak te reo Māori if they provided their own interpreters. Parliament did not again provide an interpreter for another 77 years, until 1997.

A previous ruling by speaker Frederic Lang in 1913 ordered that all Māori MPs must speak English if able, after Āpirana Ngata attempted to speak Māori without an interpreter present in order to obstruct proceedings. In 1914, Lang ruled “it is not proper, nor is it consistent with the dignity of the House, for the honourable member to speak in Māori unless his speech is interpreted.”

Does that mean te reo Māori disappeared from parliament?

Certain MPs continued to speak Māori despite a lack of interpreters, including those connected to the Rātana church and movement, who were allowed in 1930 to speak Māori if their speech was brief and an immediate translation was provided. According to NZ History, Tāpihana Paikea, a Labour Party MP from 1943-63, spoke Māori without an interpreter, using the language to send messages to his wife, who was listening on the radio.

The Māori language petition of 1972 and the kōhanga reo movement and broader push for the language’s revival in the 1980s, and subsequent recognition of Māori as an official language of New Zealand in 1987, saw a slow change to attitudes. In 1990, Labour MP and then minister of Māori affairs Koro Wētere inspired the establishment of simultaneous translation of Māori speeches in the House after causing a ruckus in the chambers by responding to questions in Māori without providing an immediate translation. He had been questioned by then National MP Winston Peters, who raised a point of order against Wētere’s use of te reo Māori, which was rejected by speaker Kerry Burke. “About a year ago I ruled on the matter that, as both languages were of equal official status, I could not require a member to give a translation following an address in the House in either of the official languages,” Burke said. “The Standing Orders clearly establish that members may speak in the House in either language, and that provision includes the asking of questions. That is a Standing Order over which I do not have discretion.”

Three years later, Peter Tapsell became the first Māori speaker of the House and, as it is “customary to have a waiata after a Māori speech”, he sang a version of Matangi: “E rere ra, te matangi/I waho Maketu/kei reira ra koe – e hine/noho wairangi ai e/mauria mai to aroha/ki i tawhiti e/waiho au i muri nei/tangitangi hotu ai e.” Afterwards, he suggested using Māori occasionally would be appropriate for formal matters.

Use of te reo Māori has picked up among Māori and non-Māori MPs in recent years, whether it be the use of commonly understood words (kia ora, mahi, motu), bilingual speeches (such as the maiden speeches of Te Pāti Māori’s fresh MPs in December) or fully-fledged Māori sentences. Despite changing attitudes towards the use of Māori in parliament, some instances – such as Kapa-Kingi’s comment to Chhour, or Te Pāti Māori opting to use “Kīngi harehare” to refer to King Charles, and possibly a skin rash – still cause controversy.

Confusion and controversy

A lack of understanding of te reo Māori can often cause hiccups in the House. In 2018, National MP Gerry Brownlee, a former Māori language teacher, raised a point of order after believing that speaker Trevor Mallard had called Nanaia Mahuta up on using too much te reo Māori during question time (Mallard had used “iti”, or small, to warn Mahuta to reduce the length of her answers, which Brownlee misunderstood to mean he wanted her use of te reo to be “iti”). Brownlee then took the opportunity to accuse Kelvin Davis of using an insult in a te reo comment the previous day. At the time, Davis argued he should not be responsible for providing a translation of what he said, and stressed the importance of context in te reo Māori, where a word can have different meanings depending on its use. (It’s likely Brownlee was referring to Davis’s use of the word “koretaketanga” in a comment that referred to “ngā koretaketanga o tērā taha o Te Whare ki te kōrero i te reo Māori”, translated in Hansard as the “ineptitude of that side of the House to speak the Māori language”.)

Two months prior, Brownlee had interrupted Davis while he was speaking in te reo to say that some MPs didn’t have the earpieces needed to hear the translation, arguing the supply of earpieces was not the responsibility of MPs. Mallard suggested MPs had been supplied earpieces but had misplaced them.

In December 2023, Te Pāti Māori co-leader Rawiri Waititi sparked debate in question time after posing a question in te reo Māori to acting prime minister Winston Peters. Gerry Brownlee, now speaker of the House, argued parliamentary Standing Orders meant the prime minister didn’t need to answer the question as “in this case, [he] doesn’t feel like he has to answer it.” Labour’s Grant Robertson argued the speaker’s ruling, while “strictly speaking” in order, did not reflect practice in his time as an MP where questions had only been refused for being “definitively out of order”. He argued that simultaneous translations in the House meant Peters, the prime minister and other MPs do have the ability to answer questions in Māori.

Who’s responsible for translating te reo Māori in parliament?

The translation of Māori language is overseen by a five-person unit called Ngā Ratonga Ao Māori, which provides translations in spoken and written form. The small department has evolved in recent years to include developing the ao Māori strategy He Ao Takitaki, to encourage further use of te reo Māori and understanding of tikanga Māori in parliament.

Parliament made its first move into simultaneous translation in 2010, allowing MPs to hear instantaneous translations via earpieces, and for Parliament TV viewers to read translated captions. While Ngā Ratonga Ao Māori oversees the official translation of te reo Māori in parliament, MPs have in the past defended using words that could have multiple translations, as was the case in the Kīngi harehare scandal (“hare” being an East Coast kupu that can be translated to “scab” or “Charles”).

According to parliament’s rulebook Parliamentary Practice in New Zealand, “an interpretation is not a polished version of what a member has said. It will always be somewhat rough and ready… Translation is a different process and takes place off the floor of the House when a speech given in te reo Māori is translated into English for inclusion in Hansard.” For that reason, there can be some delay before a translation or even the original comments in te reo Māori appear in Hansard. As of August 6, te reo comments made by Green MP Hūhana in the debating chamber on July 25 were yet to be included in the official Hansard report.