Youth parliament began on March 1. What is it, and why should you be interested in a bunch of kids going to parliament? Naomii Seah explains.

At 5:15 pm, March 1, the minister of youth Priyanca Radhakrishnan appears wearing a snazzy headset and mouthpiece combo. Next to her in the legislative council chamber is speaker of the house Trevor Mallard and next to him is clerk of the house David Wilson. Radhakrishnan, Mallard and Wilson are all appearing for the drawing of the youth parliament mock bill, which will be debated by 120 rangatahi – each selected by a current MP to represent them – over two days in July. Youth parliament has been held every three years since 1994, and this year’s session is about to kick off. It’s a tradition that ensures “rangatahi voices and perspectives are listened to, valued and really embedded in decision making,” says Radhakrishnan.

The drawing of the bill certainly looks different to when youth parliament began in 1994. It’s happening over livestream on the youth parliament Facebook page, and Wilson is diligently wearing an N95 mask. The proceedings are certainly more relaxed than a formal parliament process. It therefore might be easy to dismiss youth parliament as playing politics for kids; but if you did, you’d be making a serious mistake.

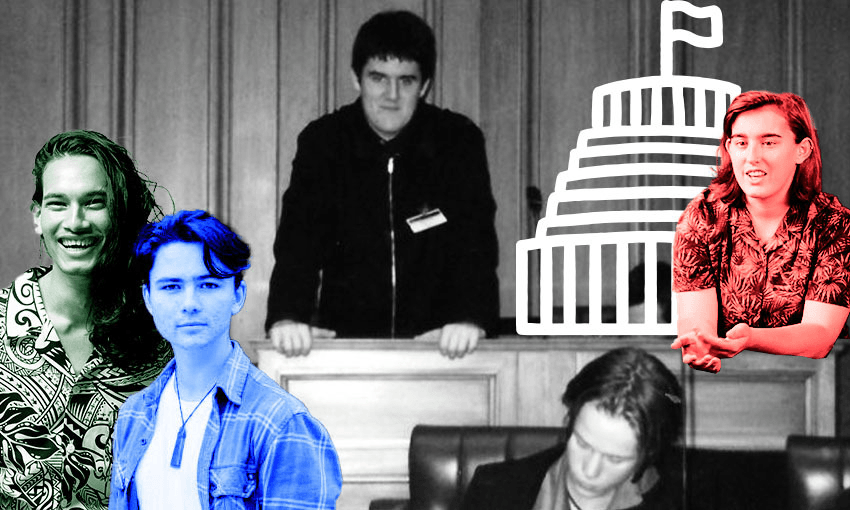

Rangatahi in Aotearoa have proven time and again that they deserve to have their voices heard. Some of our most prominent social movements in the last few years – the School Strike 4 Climate, Vote 16 and banning conversion therapy, just to name a few – have been led by our youth. And it’s not a coincidence that many of the leaders of these movements like Luke Wijohn, Sophie Handford, Azaria Howell, Molly Doyle and Shaneel Lal have participated in youth parliament.

Wijohn, Hanford, Howell, Doyle and Lal all took part in the 9th youth parliament, held in 2019. Wijohn and Handford were some of the principal organisers of the School Strike 4 Climate march, which had a turnout of over 80,000 in Auckland alone. The organisation later disbanded, releasing a statement that acknowledged their marginalisation of indigenous climate activists. But the images and the memories of the massive event live on. The movement was a testament to the very real organising power of youth. Handford has now been serving on the Kāpiti Coast District Council for three years, getting her start aged just 18. Wijohn continues his climate activism after a brief stint as a 2020 Greens candidate in the Mt Albert electorate.

During the 2019 youth parliament term, Wijohn, who was the youth MP selected by Chlӧe Swarbrick, passed a motion to declare a climate emergency in under two minutes. The motion’s success stood in stark contrast to Swarbrick’s failed attempt to pass a climate emergency in parliament just a few months earlier. A climate emergency was later declared in 2020.

During the 9th sitting of youth parliament, youth MPs Doyle and Howell called for the voting age to be lowered to 16. Howell had been championing the issue for years, penning an opinion piece for The Spinoff on it in 2018. Doyle and Howell were part of the group that launched the Make it 16 campaign which eventually brought a case to the High Court in 2020. Although the case was ultimately unsuccessful, the judge ruled that the current voting age was unjustified age discrimination, thereby leaving the door open for future campaigning. Minister for justice Kris Faafoi, who himself attended the first youth parliament sitting in 1994, has announced that parliament is set to review election laws, including the legal voting age, and a panel will report back in 2023.

Finally, after representing Jenny Salesa at the 2019 youth parliament, Lal has gone on to spearhead the campaign to ban conversion therapy, which recieved the most submissions in the history of Parliament and passed earlier this year with almost unanimous support.

Young people are already shaping the Aotearoa of the future. In fact, as the climate motion shows, the youth are ahead of the curve while the rest of us are playing catch-up. It’s clear that although the bills passed through youth parliament are “mock bills”, what happens at youth parliament is often a preview for what will be debated at parliament years later. Chris Bishop debated legalising cannabis and euthanasia at the third youth parliament in 2000, before voting through the End of Life Choice Bill as a National MP 19 years later. A climate emergency was declared in parliament one year after it was passed in youth parliament. That’s all to say that the issues debated in youth parliament today are likely to become the legislation of the future.

Rangatahi who attend youth parliament have proven their engagement, passion and drive, with many of them becoming politically influential – if not as actual politicians then as activists and advocates, or actors in the legal system. Other prestigious youth parliament alumni include Tui Dewes, New Zealand’s high commissioner to the Cook Islands, who attended the second sitting of youth parliament in 1997 alongside 2020’s breakout MP Ayesha Verrall. Labour MPs Steph Lewis, Camilla Belich and Tangi Utikere are also youth parliament alumni.

This year, youth parliament will debate the Minimum Wage (Starting-Out Wage Abolition) Amendment Bill. If passed, the mock bill would remove the almost defunct “starting-out” wage, which is defined as no less than 80% of adult minimum wage. Attendees will also participate in select committees, which will give them the opportunity to debate other issues important to them. As history has proven, it pays to pay attention to the events at youth parliament. The issues that are being debated, and the conclusions the parliament comes to, are likely to come up again in the near future. And the next time they do, it’ll be for real.

Follow The Spinoff’s politics podcast Gone By Lunchtime on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favourite podcast provider.