The former Labour communications chief talks to Toby Manhire about being proven wrong by Jeremy Corbyn, Theresa May’s ‘catastrophic’ deal with the DUP, and the chances of a Tony Blair comeback.

Tomorrow: Campbell on the Lions tour

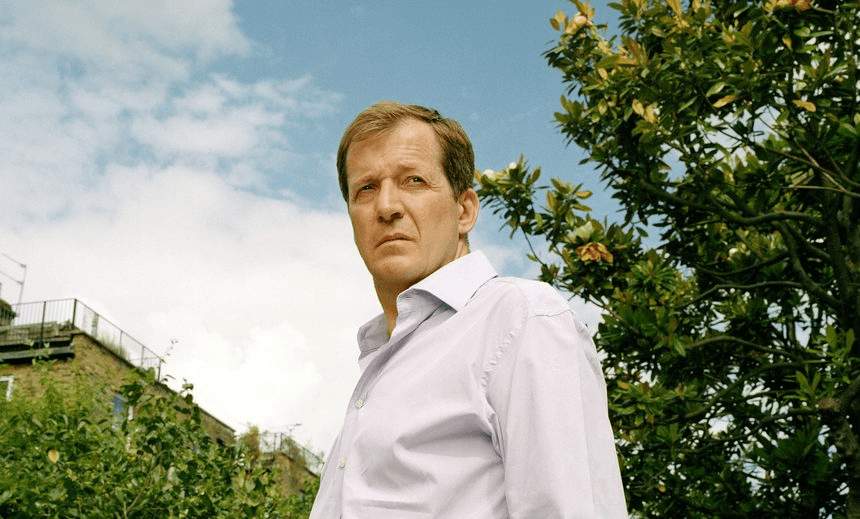

As spin doctor in chief for Tony Blair, Alastair Campbell became a massive presence in British politics – not least over his involvement in preparing the dossiers making the case for going to war in Iraq. A former journalist and author of several books, he now works as a consulting strategist and ambassador for mental health charities.

Campbell became a fresh figure of controversy over his involvement in the 2005 tour to New Zealand by the British and Irish Lions, for which Clive Woodward had appointed him head of press relations. With another Lions series against the All Blacks about to begin, the Spinoff spoke to Campbell about his memories of that tour 12 years ago – and you can read that on the site tomorrow. First, we quizzed him on the post-election fallout in Britain. As someone who predicted a Corbyn leadership of Labour would be a “car crash”, was he reassessing things? Is Theresa May imperilling the Northern Ireland peace process by dealing with the DUP? And will Tony Blair be making a return?

The Spinoff: How are you?

Alastair Campbell: I’m alright. I’m walking through sunny Regent’s Park, in one of – as my German friend called it – the world’s first first-world failed states.

I saw George Osborne, the former chancellor under David Cameron, saying on the Andrew Marr Show, with a very satisfied look on his face, that Theresa May is a dead woman walking. Is that the way you see it?

Yeah, very much so. I think it’s unsustainable for her to imagine that she can recover from the loss of authority that she’s suffered.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XNfCDSDiYY

I mean, we all know that in the end political authority is not just about numbers. If it was, Angela Merkel would not be the most powerful leader in Europe, as she is. Authority can be measured in many ways, and one of the things that you measure it by is the extent to which how big calls and big decisions play out. The fact is she took a big call on the election, and instead of exposing Labour’s weaknesses, it fundamentally exposed hers.

The whole thing was about giving her more authority for Brexit. She’s ended up with less. Also, as I said yesterday in an interview on the BBC, this thing with the DUP is just catastrophic. It’s actually horrific what she’s doing, because this a time when the British government is trying to mediate between the Unionists and the Nationalists in trying to get the Northern Ireland institutions up and running, so I think on that, on Brexit, on what it says about where we are as a country under her leadership – and I’m afraid I think there’s a leadership vacuum at the moment. I mean, she’s meeting Macron tomorrow: can you imagine a more ridiculous juxtaposition, of winners and losers. He having just utterly broken the mould and having won a landslide for the parliament, and she having completely having screwed things up.

I think she can limp on. She can get the numbers, if she does this ridiculous deal with the DUP, she can start the Brexit negotiations, but, you know, she’s fundamentally weakened. I think the only thing that’s really keeping her there is the fact that none of the people who have been mooted as alternatives are, I think, remotely credible. I mean, the idea of Boris Johnson now as prime minister, I think, is just beyond a joke.

On the DUP: you’ve been involved a lot in the Northern Ireland peace process. Can you explain to anyone who may not be familiar with the political process there why it matters if the DUP is to become part of the embrace of the Westminster government?

The party that we mainly dealt with, until Ian Paisley came to the fore, was the Ulster Unionist Party, the UUP. The Democratic Unionists are, if you like, much more Unionist.

So there’s two things. The one that is commanding the most attention here is the fact that the DUP do have these extraordinarily socially conservative positions, which most people in Britain find very difficult, whether that’s on gay rights, or abortion, or whatever. There’s been a lot of focus on that.

But for me, the real significance of their place in this is their position in the peace process. The DUP and Sinn Fein are, if you like, two sides of the divide that we have, more or less successfully, managed to straddle. Back in the early 90s, Peter Brooke, who was then the Northern Ireland secretary, made a very, very important speech. He basically said – and this became the start, really, of the process that led to the Good Friday Agreement – he basically said that the government, the British government, had no selfish strategic interest. We, as it were, were neutral between Nationalists and Unionists. So how can you be neutral?

We’re in a situation now, for example, where the administration has been suspended because of a political crisis a few months ago. The British and Irish governments, their role in the Good Friday Agreement, when the institutions are suspended, their role is to act as mediator. How on earth can you be the mediator when one of the parties is now propping them up? As Jonathan Powell [chief UK negotiator on Northern Ireland 1997-2007] said yesterday, effectively the DUP can now hold Theresa May hostage. That’s unsustainable for the peace process. And it just underlines how desperate she is, frankly, to cling on.

On the other side of the ledger in the UK, there’s Jeremy Corbyn, who looked if anything even more satisfied that George Osborne on the TV. I mean, if you’d been beamed in from space you’d have felt certain Jeremy Corbyn had won the most seats in the election and not Theresa May, and –

I’ve been doing some work in the Balkans, and a friend of mine in Albania, who was watching on television, sent me a message saying, “Why are the losers behaving like winners and the winners behaving like losers?” And I think again we’re back to the point about expectations. If your expectations are very low, and you surpass them, then you can project it as a success. I basically think, you know, stop the celebration and just reflect on the fact that we didn’t win.

Now, Corbyn has certainly fought a better campaign than most of us expected him to. He tapped into this whole thing about austerity. He motivated a lot of people to vote for the first time. That’s all good, but against a really terrible, truly terrible Tory campaign, with somebody exposed as being utterly not up for the job, with the health service imploding, social care imploding, Brexit looming as a catastrophe, we’re still considerably well behind the Conservatives. So I don’t think we should get carried away.

But you did say a couple of years ago that Corbyn was a “car crash”, that he could drag the Labour into oblivion. You weren’t alone in that. But have you had cause to revisit that assessment?

Yeah. Look, we’ve not been wiped out, that’s true. And I’m not going to take anything away from the fact that he’s tapped into something in a way that I didn’t think he would. But for all that people say the fundamentals have changed, that there’s no such thing as the centre ground, and all this, to get the majority in our country, with the system that we have, you have to be able to build a coalition of support across the spectrum.

He did very well with young people. But at the moment, I don’t think the Labour Party leadership fully understands the extent to which this was also, this rejection of Theresa May, was also a rejection of her approach on Brexit. I don’t think that our approach on Brexit is sufficiently different. So there’s a lot of stuff in there. Like you say, if you’d have landed from Mars you’d have thought Jeremy Corbyn was prime minister in a landslide. We’re a long way from that. And I still think the public have real reservations. It’s up to him, and it’s up to the rest of the people in the Labour Party to persuade the public that that bridge can be filled, between what they think and what’s holding them back from voting Labour.

And don’t forget, as well – and this is something that I’m not making this as an anti-Corbyn point –there were lots of people who, frankly, voted Labour in part because they were worried that Theresa May was going to get a massive majority. There were Labour MPs, Labour candidates, who openly were going around the doorsteps saying, look, vote for me, I’ll be your MP, and don’t worry, we’re not going to win. They were saying that, publicly, because they knew that for all that he was inspiring and enthusing some people, there were other people that we were losing because we’d moved so far away from the centre ground. So, it’s a very complicated picture. It’s too simplistic, either to say that all the Tories’ faults were down to Theresa May, or all the Labour gains are down to Jeremy Corbyn. It’s much more complicated.

But it’s always complicated, isn’t it? It was interesting reading a piece that your son wrote for the Guardian before the election. He’d started, I think, from the same point as you, but he’d come around to the idea, even before the election that Corbyn was what was wanted, and what was needed. Are you open to that perspective now in a way you weren’t before?

I think I’m more open to it, but I’m less persuaded that that is going to be the means by which the country elects a Labour government. To be fair to Calum, my son, who has a very, very astute political mind – he predicted Brexit and he predicted Trump, some way out – and as it says in the piece, it’s basically this sense that if people feel disengaged enough, if they feel that they’re not being heard, not being listened to, the world is not really improving the way that politicians say, they’re going to give the politicians a kicking. And just to complicate it further, a lot of what is happening in votes around the world at the moment is kind of anti-establishment, anti-politics, anti-mainstream, whatever. So, for example, you look at Scotland, there’s all sorts of reasons why the Scottish National Party – they still did well in one sense, compared to 10, 15, 20 years – slid backwards is because now they’re the establishment there. It’s not Labour who is the establishment in Scotland, it’s not the Tories, it’s the SNP. So they got a kicking. In England, it’s very much the Tories. And Jeremy Corbyn, because he’s a very good campaigner, he was able to project himself, if you like, as the anti-establishment protest politician. And he did very well on the back of it.

What about your old mate Tony Blair. There was talk some months before the election, following a piece, I think, in the New Statesman. Is there any return of the Tony Blair bus happening any time in the future?

I think that got completely overblown in terms of how people interpreted it. What I think is right, is Tony accepts that his brand, if you like, his reputation, is not remotely as powerful as it was in 1997. But he is still a huge figure, and what’s more he has, I think, a really good political mind. And if you like, the election has sort of borne this out: if you give the country the choice of a very leftwing Labour Party and a very rightwing Tory Party, committed to this ruinous hard Brexit approach, then a lot of people are going to end up feeling politically homeless and voiceless. For all the excitement that’s been generated by the Tories being stopped from getting back with a majority, that remains the case.

But you’re not going to see Tony Blair standing for parliament again. People should just forget that.

This content is brought to you by LifeDirect by Trade Me, where you’ll find all the top NZ insurers so you can compare deals and buy insurance then and there. You’ll also get 20% cashback when you take a life insurance policy out, so you can spend more time enjoying life and less time worrying about the things that can get in the way.

This election year, support The Spinoff Politics by using LifeDirect for your insurance. See lifedirect.co.nz/life-insurance