The Covid response and Jacinda Ardern’s personal popularity were the decisive factors, while talk of strategic anti-Green voting appears to have been overblown. Researchers from the University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington share the key insights from their survey of 2020 voters.

Nine months out from the 2020 election, opinion polls suggested it would be a close race between Labour and National. But that all changed with the arrival of the global pandemic.

Covid came to dominate the policy and political agenda from March 2020, ensuring Labour focused its re-election campaign firmly on its pandemic response. As Jacinda Ardern said at the campaign launch, “When people ask, is this a Covid election, my answer is yes, it is.”

The result was resounding. On October 17, Labour won an unprecedented victory, forming the first single-party majority government of the MMP era. It was the largest ever swing to an incumbent in the history of New Zealand politics.

So what does this result tell us about electoral politics in the context of a global crisis, and the role of incumbency, leadership, trust?

The voters speak

When it comes to analysing an election result, changes in party vote or seats give us an overall picture. But to understand why the electorate votes the way it does we need to consider the choices made by individuals.

The New Zealand Election Study (NZES) allows us to look at a random sample of individuals drawn from the electoral roll, and to test some of the factors we know influence voting behaviour.

The NZES has been conducted after every general election since 1990. In 2020, we surveyed 3,731 participants whose views and votes provide us with a unique insight into the complex interplay of variables that might determine an election result.

Here we highlight some of the topline numbers from our analysis of the 2020 NZES to cast light on what led to the historical election outcome 12 months ago.

Covid overshadowed all

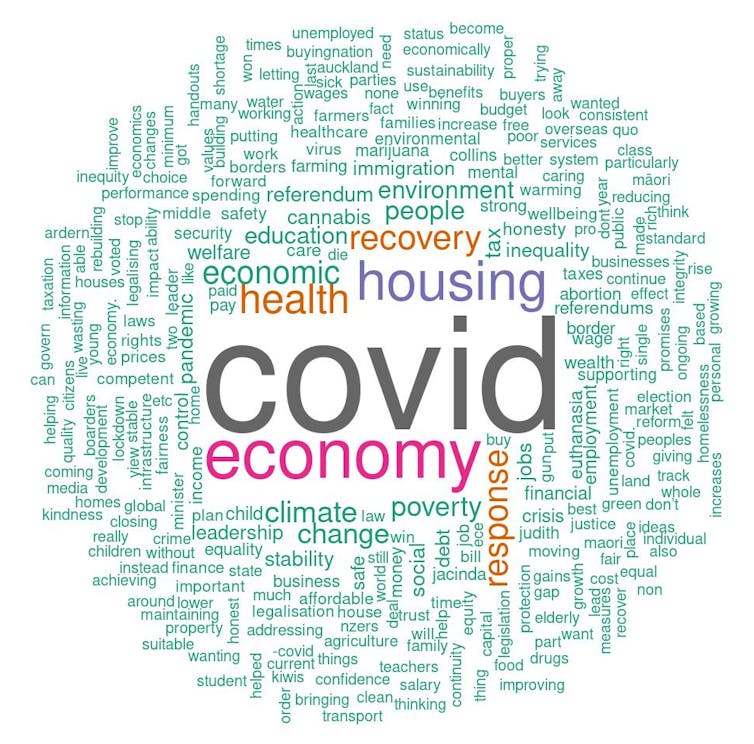

The data reveal that 2020 was indeed a Covid election. For instance, we asked people to say what they thought was the most important issue of the election. As our word cloud below shows, Covid was clearly the most mentioned issue, and ranked above many issues traditionally seen as important during election campaigns.

Moreover, the public overwhelmingly supported the government’s response to Covid, with 84% of people approving or strongly approving, while only 6% disapproved.

Of those who approved or strongly approved of the response, 57% reported casting a vote for Labour (9% voted Green, 3% New Zealand First and 1% Māori Party), while only 19% voted for National.

The majority (50%) of people who disapproved of the government’s Covid response voted for National, and a further 19% for Act, while only 8% voted for Labour.

Strategic anti-Green voting unlikely

National’s loss and Labour’s win sparked a number of speculative explanations. For example, Labour’s gains in provincial electorates were claimed to be a result of strategic voting by farmers anxious about Green Party policies and water reform.

Federated Farmers Mid-Canterbury president David Clark argued that “plenty of farmers have voted Labour so they can govern alone rather than having a Labour-Greens government”.

But our analysis of the NZES data reveals only a small change in the farming vote between parties. A majority (57%) of those in farming occupations voted for National and 21% voted for Labour. These numbers contrast with 2017 when National received 67% of the farming vote and Labour just 8%.

On the other hand, Act’s share of the farming vote increased from 2% to 16%, while the NZ First vote collapsed from 13% to less than 1%.

While these observations are based on a very small sample size of farmers, and should be interpreted with caution, our findings indicate the combined National-Act vote was relatively unchanged – making the anti-Green argument a little far-fetched.

The Ardern factor

Looking at the responses of all voters in our study, we find that of those who switched from National in 2017 to Labour in 2020, 46% placed themselves at the centre of the political spectrum, compared with 25% of voters who voted for National in both the last two elections.

This suggests these centre voters may have always been open to switching from National to Labour, casting further doubt on the strategic voting claim.

The popularity of Jacinda Ardern – and the lack of popularity of Judith Collins – is also highly likely to have contributed to Labour’s success. Of our NZES respondents, 65% said they most wanted Ardern to be prime minister on election day, compared to only 17% supporting Collins (no one else received over 2% support).

When asked to rate leaders from 0 (strongly dislike) to 10 (strongly like), 33% of people gave Ardern 10, and 69% gave her a 7 or above. In contrast, only 22% of people gave Collins a 7 or above, and 23% gave her 0.

Labour’s new voters

We found, unsurprisingly, that likeability and trust are highly correlated, but we also found trust in Ardern as leader was statistically significant in explaining the shift to Labour, even after controlling for how much people liked or disliked her, their prior vote, and their left-right positions.

This supports assessments from around the world that decisive and rapid responses to Covid-19, combined with clear communication, can lead to increased trust in political leaders.

We also know Labour won nearly half a million new voters compared to 2017. Where did this support come from? Around 16% of 2020 Labour voters reported voting for National in 2020, while 13% stated they did not vote in the previous election.

Of the new Labour voters, the majority (55.5%) were women and just over half (51%) were under the age of 40, with 33% Millennials and 18% Gen Z. When asked which party best represented their views, 58% chose Labour and just 11% chose National.

However, when asked if there was a party they usually felt close to, only 29% reported feeling close to Labour, while 53% did not feel close to any party.

Non-Covid concerns a warning

Our NZES data clearly show the 2020 New Zealand general election can indeed be thought of as a Covid election. Support for the government’s rapid public health and economic policy responses, and the popularity of Ardern, go a long way to explaining the outcome.

However, as the word cloud suggests, there are a number of policy issues that remain of concern to voters, including housing, health and the economy. These were issues that featured in 2017 and may continue to matter through to the 2023 election.

Our preliminary analysis, then, is a reminder that Labour cannot take its new voters for granted.![]()

Josh Van Veen, Research Associate, Public Policy Institute, University of Auckland; Jack Vowles, Professor of Political Science, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington; Jennifer Curtin, Professor of Politics and Policy, University of Auckland; Lara Greaves, Lecturer, University of Auckland, and Sam Crawley, Postdoctoral fellow, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.