Australia’s decision to revoke the citizenship of a dual citizen, who has lived in Australia since the age of six, has prompted a furious response from the New Zealand prime minister. ‘They did not act in good faith,’ she said.

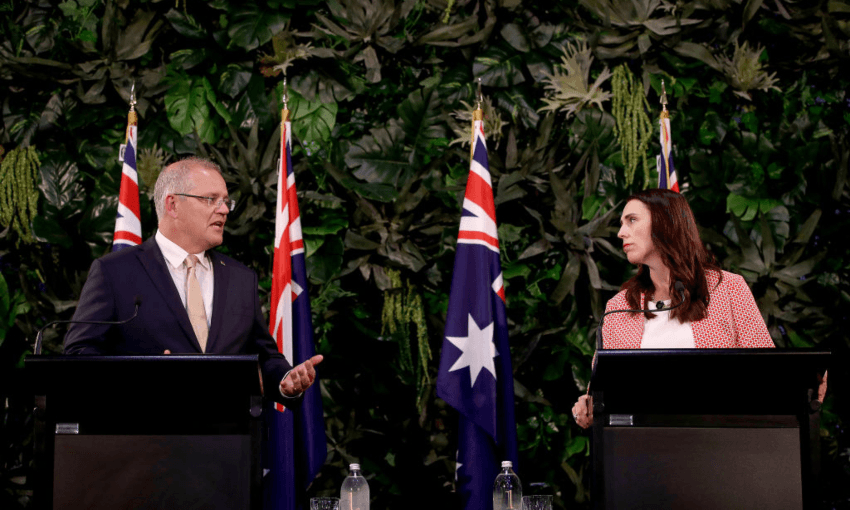

In blunt and dramatic contrast to the typically cordial tone of trans-Tasman relations, Jacinda Ardern this afternoon expressed her fury at her Australian counterpart, publicly lashing out at Scott Morrison after he revoked the citizenships of a woman and two young children detained at the Turkish border.

At the centre of the conflict between Wellington and Canberra is a 26-year-old woman who was recently detained, reportedly while attempting to clandestinely exit Syria. Turkish authorities say she’s an Islamic State terrorist. She was also an Australian citizen – until recently.

Today’s acrimony signals a profound breakdown in New Zealand’s most important international relationship that has little precedent in modern history, an expert warns. Strained relations between both prime ministers, which have slowly disintegrated with continuing deportations of New Zealanders by Australia, now looks to be on life-support.

According to the New Zealand prime minister, the woman had lived in Australia for the past two decades. Her family and friends are in Australia. She travelled to Syria on an Australian passport. She was an Australian. She was however born in New Zealand, a country she left at the age of six. Which also makes her a New Zealand citizen by birth.

Ardern raised the issue of the woman when authorities first detected that she was headed to Syria. Ardern told reporters today that she wanted the two governments to come to an agreement for how to deal with dual citizens who could be terrorists. Instead, Australia revoked the woman’s citizenship, making her solely New Zealand’s problem.

“You can imagine my response,” Ardern said today at parliament about when she learned of what Morrison had done. “I think New Zealand, frankly, is tired of having Australia export its problems. But now there are two children involved.”

Instead of coming up with a plan, the Australians had walked away from their own problems, said Ardern. She had warned Morrison repeatedly that she would “very strongly” react to his decision once it become public. She warned him again this morning, after the woman’s arrest was reported, that a public lashing was imminent.

“I never believed that the right response was to simply have a race to revoke people’s citizenship. That’s just not the right thing to do. We will put our hands up when we need to own a situation, we expected the same of Australia. They did not act in good faith,” she continued.

“I will finally add: If the shoe were on the other foot, we would take responsibility, that would be the right thing to do. I ask of Australia that they do the same.”

New Zealand is unable to simply follow Australia’s lead and cancel the woman’s citizenship and that of her children; that would make the woman stateless, something barred by international law.

Alexander Gillespie, an international law professor from the University of Waikato, said that while Australia hasn’t violated international laws, what it did is ethically wrong. “This just isn’t the way that countries that are good friends should act,” he said.

Australia has adopted an unusually harsh response to citizens that head overseas to commit terrorism, revoking citizenships and refusing repatriation in most cases. The United States and most European countries have instead sought to bring their citizens home, either to face justice or counselling.

Morrison was unapologetic when asked about the move during a press conference in Canberra.

“My job is Australia’s interest, that’s my job,” he told reporters there.

Legislation in Australia automatically cancels a dual-citizen’s citizenship when they engage in terrorism, he said. The two prime ministers are scheduled to speak later today.

“Australia’s interest here is that we do not want to see terrorists who fought with terrorism organisations enjoying privileges of citizenship,” he said.

Today’s exchange across the Tasman is an important moment in the relationship between both countries, and not in a good way, said Robert Ayson, professor of strategic studies at Victoria University.

“I don’t remember a New Zealand prime minister being this obviously angry about anything that an Australian leader has done. And my memory goes back some way,” he said. “I think we can say there is a serious problem in this relationship now.”

The use of the term “bad faith” by Ardern, which is about as damning a phrase as diplomacy allows, was quite striking, he said.

Ardern’s public revelation that she’s tried, repeatedly, to warn Morrison about her anger shows that she’s concluded he just isn’t listening, said Ayson.

“When your most important international relationship isn’t working, that’s a real problem,” he concluded.

This is not the first clash between the two leaders. During a press conference in Sydney a year ago, days before both countries went into lockdowns in the face of Covid-19, Ardern told Morrison “do not deport your problems” over his treatment of New Zealand citizens.