In the aftermath of Yoon Suk-Yeol’s attempted insurrection, South Koreans around the world have been making their voices heard as they defend their homeland’s democratic institutions. Aotearoa is no exception, explains Rebekah Jaung.

As we forge on ahead

Those who live, follow on

– from the song ‘March for Our Beloved’, poem by Paek Ki-wan, lyrics by Hwang Sok-Yong. Composed in 1981 and first officially released in 1991.

Can the past help the present?

Can the dead save the living?

– from Han Kang’s Nobel lecture published December 7, 2024.

When the terrifying prospect of martial law became a reality, it was Gwangju in May 1980 that led us here in December 2024.

– from the speech of floor leader for the Democratic Party Park Chan-Dae preceding the vote to impeach Yoon Suk-Yeol on December 14, 2024.

At 10.25pm local time on December 3, 2024, then South Korean president Yoon Suk-Yeol gave an emergency presidential address to the nation saying he was “declaring emergency martial law”. This was the first declaration of martial law in the country in 44 years, and the first time the country had been in this state (albeit briefly) since it became a democracy in 1987.

News from the homeland always reaches diaspora communities with a bit of a lag due to living in different time zones, so I only realised something had happened when I saw that the group chats had gone wild overnight. Someone posted the text of the martial law declaration at 3.30am, which was followed by a barrage of “Is this real???” then screenshots and confirmation from those living in Korea, which were soon followed by more official news articles accompanied by exclamations of disbelief. Watching the footage of lawmakers jumping over fences and wrestling with police in riot gear to enter the grounds of the National Assembly, helicopters full of soldiers landing on the lawn and people wresting guns away from the martial law forces simultaneously felt surreal, violating and, in watching the resistance, heartening.

For those who had lived experience of martial law, including surviving the May 18 Gwangju Democratic Uprising in 1980, as described by our first Nobel laureate Han Kang in her novel Human Acts, martial law is synonymous with fear and repression. For those like me, who have learnt about this period from history books and other people’s memories, it felt like we had stepped back in time. The first quotation in this piece is an excerpt of a song that is synonymous with May 18 and sung at the annual commemoration of the event. The true number of casualties inflicted by the martial law forces on the civilians of Gwangju is still unknown, and it was only discussed in secret and at risk of detainment and torture until the end of martial law. If you want to learn more about this foundational event in modern Korean history, there are many other beautiful (and devastating) works made in its memory including: A Taxi Driver (film, 2017), 26 Years (animated film, 2012), May 18 (film, 2007) and Youth of May (series, 2021). Or attend a local in-person or virtual commemoration event this coming May.

The terrifying similarities between what happened in 1980 Gwangju and what could have happened on the night of December 3, 2024 keep cropping up as more details from Yoon’s insurrection attempt emerge. Not only is the text of the two martial law proclamations nearly identical, there are growing allegations that the plan involved goading North Korea into an altercation (read war) in order to justify the declaration of martial law – the justification that was used by the Chun Doo-Hwan military dictatorship to justify the brutal massacre in Gwangju.

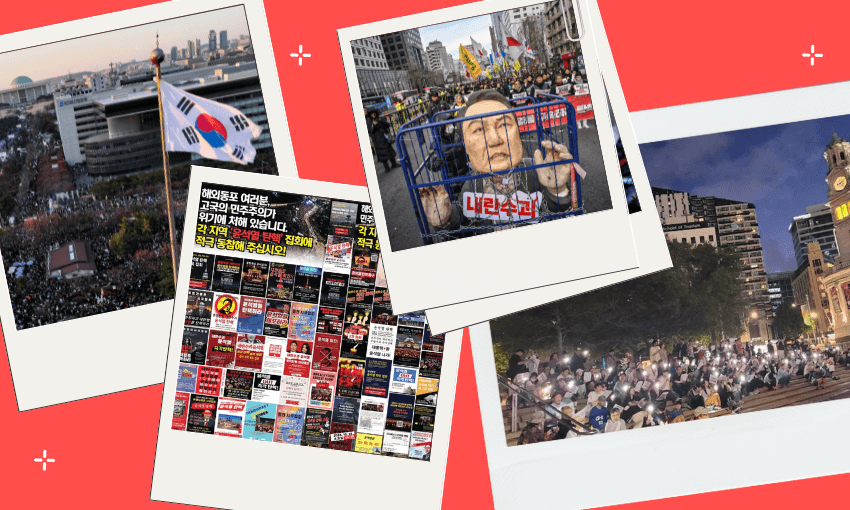

Returning to 2024, the whole night’s events only took six hours but seem to have changed everything. The weekly protests calling for the impeachment of Yoon Suk-Yeol have been running continuously for more than two years in response to mounting suspicions about corruption, including those regarding his wife Kim Keun-Hee. But the protests that had previously been attended mostly by stalwart activists have become a daily event that, according to protest organisers, gathered over a million attendees on the weekend of the self-coup attempt.

For those whose view of South Korea is from a greater distance, the sight of massive protests on the streets of Seoul and other cities may seem familiar. The last conservative administration headed by Park Geun-hye was felled in 2017, when an abuse of power scandal peppered with absurd details (shamanism, an obsession with K-dramas and the Korean Olympic equestrian team) was the final blow to a presidency already weakened by events such as the Sewol Ferry Tragedy and the police killing of farmer Baek Nam-Ki at an earlier mass protest. South Koreans showed up to weekly protests in their millions and overseas Korean networks, including those in Aotearoa, were activated to make their voices heard in defending Korea’s democratic institutions.

This round of protests has been marked by the emergence of a new generation of participants. Younger people, ranging from high school students to those in their 30s, with no lived experience of martial law themselves, have turned up in their thousands, with new iconic protest items such as K-pop light sticks and internet culture-coded “nonsense flags” for organisations such as “Korean Swifties: Friendship Bracelet Department”, and “Angry Animal Crossing Residents Neighbourhood Association”. For adults, this new generation of protesters elicit both fierce pride and heartbreak, as even a nine-year-old Korean can now say they have lived through two impeached presidents.

The images of the peaceful and community-minded protesters also echo the legacy of Gwangju. The uprising was led by students and was taken up by the wider community when two students were killed by martial law forces, and even when the city was under siege, citizens lined up to donate blood at the hospital and shared rice balls so that no one would go hungry. The fact that the huge gatherings of 2016 and 2024 could occur without significant incidents, and the trend of pre-paying for coffee, snacks and meals at shops in the area of the protests and tidying up afterwards, exemplify the Gwangju spirit of civic mindedness despite the disarray in the country’s highest offices.

Protests were also held in at least 45 cities globally. In Aotearoa we have had protests in both Tāmaki and Ōtautahi over the past two weeks, with the second Tāmaki protest gathering over 150 people. Held the night before the impeachment vote on 14 December, we sang together, shouted slogans, played the rising k-pop protest anthems and even had a donor pre-pay for drinks at a nearby cafe. Thankfully, the impeachment vote at the national assembly the next day passed, meaning that the process of impeaching Yoon Suk-Yeol now moves to the Constitutional Court for ruling – Yoon and his supporters have vowed to challenge every step.

Although a lot remains unclear, waking up to a day when a dangerous man did not have control over the military of our homeland was a huge relief. Reflecting on all that has happened over the last fortnight, despite the initial fear and the yet to be fully ascertained economic and other consequences of this threat to our democracy, the people of Korea have shone. Perhaps it is the hard-won prize of all we have endured, what we have survived and what (who) we have lost in our struggle for independence and democracy, but when it really matters, it is the collective that comes to the fore. At this time in global politics, when many people are feeling powerless and disempowered, the lessons of Gwangju 1980, Busan-Masan 1979, Seoul 1987 and Korea 2024 may serve as a reminder that democracy is an active process. In the words of the third South Korean who went through the impeachment process but was reinstated by the Constitutional Court:

“Democracy has no endpoint. However history continues to progress… The final fortress of democracy is the organised power of an awakened citizenry. This is our future.” (Roh Mu-Hyun)