Rushed-in changes risk burning out teachers and overwhelming our most vulnerable students, argues principal Martyn Weatherill.

Parents may be wondering why teachers and principals asked the government last week to pause the fast-track implementation of new structured maths and English curricula by Term 1 next year. It isn’t because we are stubbornly resistant to educational change, or because we do not care about children’s needs. It’s because we want any change to work and to lead for success for students, not to burn out our teachers and overwhelm our most vulnerable students.

According to a current NZEI Te Riu Roa survey, 77% of principals and 73% of teachers believe the curriculum changes are happening too quickly for them to be implemented effectively. They report that on average, 30% of their students have additional learning needs, and two-thirds of educators feel that fast-tracking the curriculum changes will not do anything to meet the real needs of kids in their school.

“If teaching was maths, writing and reading, and the other important learning areas, and students were all learning at approximately similar levels, no problem,” one teacher said. “It’s when society expects us to parent, provide psychological support, toilet train, manage anxiety, be trauma informed, and maintain our own work-life balance – there are not enough hours in the day.”

“Student outcomes are linked to lack of support, so the pace is one thing,” A principal said, “but neglecting the needs is the worst part – how are all children going to achieve without support?”

Minister Stanford appears to hold the misguided notion that curriculum changes can be delivered by simply putting down one book and picking up another, which will then automatically lead to more students succeeding.

Any educator will tell you this is not how it works. Curriculum change is at least a year-long piece of work which needs to be implemented with care and ongoing professional learning. Careless implementation (which is what we are being told to do) works against effective learning.

We need careful delivery to optimise successful learning for children, and this conversation is not happening at government level; it is happening between teachers and principals. We are the ones asking the fundamental question that is absent at the ministerial level: what do children need to learn and succeed? Teachers and principals – who already juggle complex work demands – will ensure they are prepared and bring the right approach to the classroom so students can learn and thrive. Without such careful delivery, the feeling amongst many teachers is that the rate of change is tantamount to experimentation.

“It is important that we implement change with integrity,” one respondent to the NZEI Te Riu Roa survey said. “The current pace of change is a barrier to this happening. I am concerned that we will end up with rushed implementation that undermines both teaching and learning.”

The fast-tracking of the new maths curriculum – which was supposed to be implemented in 2026 and is now being rushed in by January 2025 – is the straw breaking the camel’s back for many in our sector. The “structured maths” curriculum, published and open for consultation for just four weeks, has not gone through a robust evidence and testing process and has been roundly criticised by maths experts as a result.

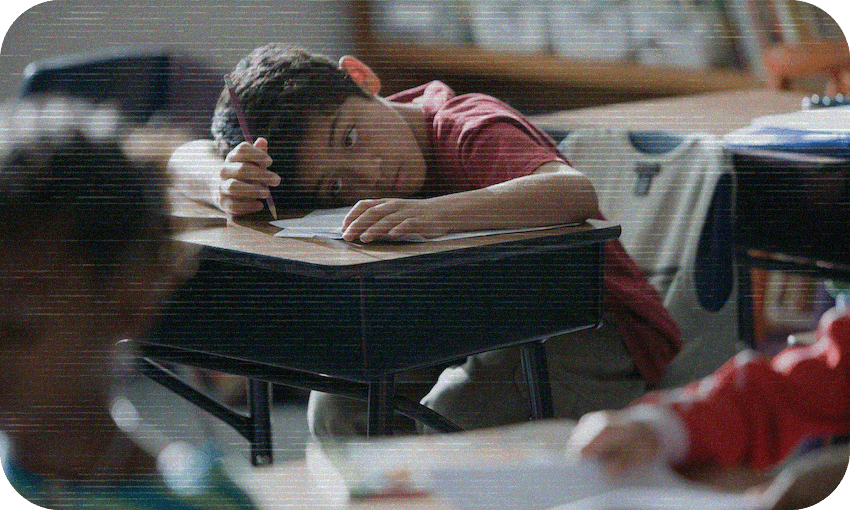

Prescriptive workbooks will not work for all learners. Teachers need to be able to provide the right learning, for the right student, at the right time. That is the key to successful learning. The worst-case scenario I anticipate is a lack of learner engagement leading to behavioural issues because of teachers and principals having to implement a rigid curriculum that does not engage students. Because when students are bored, they act out. When students are overwhelmed and stressed, they act out.

Narrow curricula options make teaching literacy and numeracy a box-ticking exercise and risks seeing many children become disengaged. No teacher wants to see 29 bored children in a classroom because there are no alternatives to a highly prescribed and mandated approach.

There is plenty of room to improve how children learn. But we are concerned that the improvements we have identified time and time again, such as increased funding for learning support needs, remain ignored. In my school, 90% of my students are good at maths. They are not being failed by the education system. The remaining 10% don’t need a new curriculum. They need learning support.