In the third of Guyon Espiner’s extended interviews with former prime ministers for RNZ, Jim Bolger, who led the National Party to power in 1990 pledging to return the ‘decent society’ to New Zealand, criticises the prevailing economic orthodoxy, saying it has led to a dangerous gap between rich and poor.

Bolger defends the record of Ruth Richardson, who as finance minister introduced what she called the ‘mother of all budgets’, saying they had been blindsided by a Labour government which bestowed them ‘an economy that was heading towards bankruptcy’. He says, however, that subsequent governments have failed to protect core New Zealand values of fairness under neoliberal economics, and ‘demonstrably that model needs to change’. He goes on to say that while the Employment Contracts Act was essential to curb industrial action debilitating the country, union membership was now lower than is healthy, with unions ‘probably too small now to have the influence they should have’.

The prime minister who oversaw the Sealord deal and the ‘fiscal envelope’ says it was essential for New Zealand that the crown pursue settlements with Māori, and that he and Doug Graham, then minister in charge of treaty negotiations, had privately discussed the idea of an upper house with a 50% Māori composition. He has a few choice words for Don Brash, too, invoking another Donald, who lives in Washington, and noting the ‘absurdity’ of the Hobson’s Pledge campaign. And he calls on his National Party successors to boost the refugee intake: ‘The government knows my views on that.’

Bolger also recalls the ‘huge disappointment’ of the 1997 coup, hatched while he was overseas, that saw him replaced by Jenny Shipley. While MPs hoped to improve their electoral fortunes, the tactic had ‘failed’ in the examples of Shipley, Geoffrey Palmer and Mike Moore, prime ministers who came to power without a general election mandate, says Bolger. ‘The public obviously doesn’t buy that argument.’ Tempting though it might be to regard that as casting shade on Bill English, it bears noting that Bolger – as Espiner told the Spinoff a fortnight ago – was speaking before the new PM got the nod: on the very day, in fact, that John Key resigned.

Here Espiner reflects on the conversation, which you can watch below.

Scroll down to watch the interview. View the interview with Geoffrey Palmer here, and with Mike Moore here; review the series as a whole at RNZ. The Spinoff’s interview with Guyon Espiner about the project is here.

I think Jim Bolger might be about to spark a debate. Two debates actually. One on our economic settings and the other on race relations. He says neoliberalism has failed and suggests unions should have a stronger voice. He says Treaty of Waitangi settlements may not be full and final and that Māori language tuition should be compulsory in primary schools.

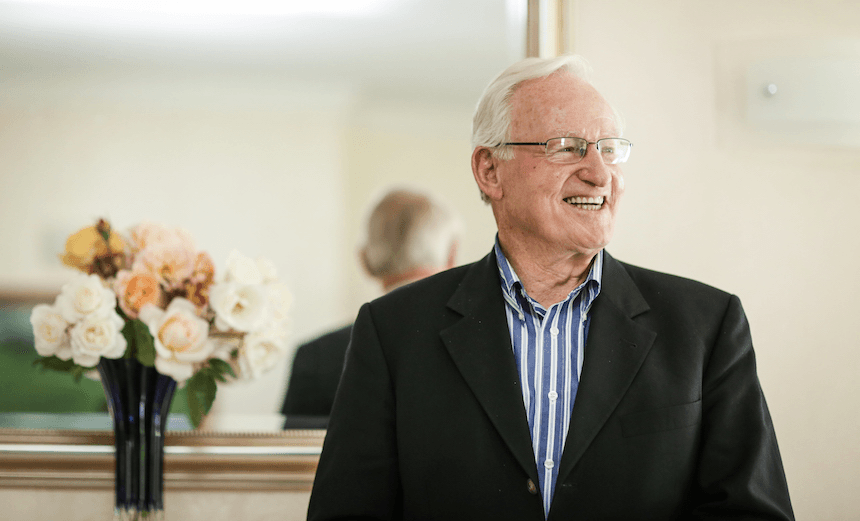

It was striking, sitting in Jim Bolger’s Waikanae home for the third episode of The 9th Floor, just how many of the issues he grappled with in the 1990s are still alive and being debated rigorously today. Adding to that sense of history was the fact that John Key resigned while we were discussing with Bolger what it was like to be a third term National prime minister.

There was a little bit of personal history for me too and we’ll come to that. But first the policy. Bolger says neoliberal economic policies have absolutely failed. It’s not uncommon to hear that now; even the IMF says so. But to hear it from a former National prime minister who pursued privatisation, labour market deregulation, welfare cuts and tax reductions – well, that’s pretty interesting.

“They have failed to produce economic growth and what growth there has been has gone to the few at the top,” Bolger says, not of his own policies specifically but of neoliberalism the world over. He laments the levels of inequality and concludes “that model needs to change”.

But hang on. Didn’t he, along with finance minister Ruth Richardson, embark on that model, or at least enthusiastically pick up from where Roger Douglas and the fourth Labour government left off?

Bolger doesn’t have a problem calling those policies neoliberal although he prefers to call them “pragmatic” decisions to respond to the circumstances. It sets us up for the ride we go on with Bolger through the 1990s, a time of radical social and economic change.

Judge for yourself whether or not they were the right policies but do it armed with the context. Bolger describes his 17-hour honeymoon after becoming PM in 1990. He recalls ashen faced officials telling him before he was even sworn in that the BNZ was going bust and if that happened nearly “half of New Zealand’s companies would have collapsed”.

The fiscal crisis sparked the Mother of All Budgets and deep cuts to the welfare state. Some believe this was the start of the entrenched poverty we agonise about to this day. How does the man whose election slogan was “The Decent Society” feel about that now?

There is so much to the Bolger years. The first MMP government with Winston Peters, the economic growth of the mid-90s, the birth of Te Papa and the first big Treaty Settlements.

Indeed Bolger is at his most passionate speaking about Māori issues. He has a visceral hatred of racism and explains the personal context for that. We asked him whether future generations will open up Treaty settlements again – given Māori got a fraction of what was lost – or whether they are genuinely full and final. He says it is a “legitimate” question and “entirely up to us”. If Māori are still at the bottom of the heap “then you can expect someone to ask the question again because it means that society has failed”. He is also scathing of former National leader Don Brash’s Orewa speech on “Māori privilege”. “It wasn’t anywhere near as bad as Trump but it was in that frame.” Of course Don Brash never made it to PM, replaced by John Key in 2006. Gone by lunchtime was the political phrase popular at the time.

When we returned to Bolger’s house after our lunch break, Key was gone, too, one of those rare times when “shock resignation” is an accurate headline. Bolger was buzzing as we talked long into the afternoon, feeling fate had settled in with him on the big chair in the lounge of his stately home.

I felt it, too. My first day as a political reporter was Bolger’s last day as an MP. I was asked to cover the valedictory for The Evening Post, a task I felt hopelessly ill-prepared for. In his parting words to parliament in April 1998, Bolger looked up at the Press Gallery and invited us to “take out your quills and bury me one final time”. We’ve done the opposite here, I hope, and dug up the past for The 9th Floor. It’s 19 years later – almost to the day – and I think we’re all a little bit better prepared to look at his legacy.

This content is brought to you by LifeDirect by Trade Me, where you’ll find all the top NZ insurers so you can compare deals and buy insurance then and there. You’ll also get 20% cashback when you take a life insurance policy out, so you can spend more time enjoying life and less time worrying about the things that can get in the way.

This election year, support The Spinoff Politics by using LifeDirect for your insurance. See lifedirect.co.nz/life-insurance