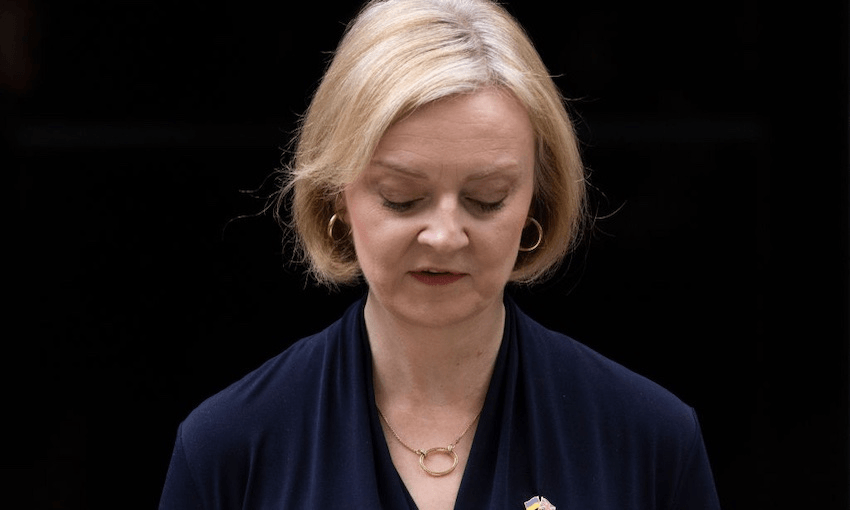

Liz Truss became the shortest-serving prime minister in UK history overnight. Henry Cooke explains how this all happened and what might happen next.

Sometimes politics happens slowly. No one really thought Theresa May was going to make a whole term after her disastrous 2017 election and the Brexit fumbling that followed, but it took until 2019 for Boris Johnson to actually take over, and months for him to fall.

Other times it happens very quickly. Over the weekend, after Liz Truss’ new chancellor had managed to calm the market turmoil somewhat, it looked like she might be able to limp on for months, without much power but still in office. Today she resigned – leaving open the possibility of Johnson returning to power.

What pushed her over the edge?

The short version: She alienated the wing of the party that had helped elect her while also pissing everyone else off, after causing serious harm to the economy and cratering her party’s polls.

The slightly long version: Liz Truss has not really had a good day in office, but Wednesday (UK Time) was particularly bad.

The papers were aflutter with rumours that the government would give up on the sacred “triple lock” on pensions – basically a guarantee that pensions go up by a decent amount every year. Her staff and fellow cabinet ministers were very clearly not denying these rumours.

At Prime Ministers Questions (think Question Time, but just her) she recommitted to the triple lock, leaving many to wonder why exactly she had allowed the rumours to start and dominate the news agenda if she wasn’t actually going to do the big unpopular thing in the end.

But that news was soon swept away as her hardline right-wing home secretary Suella Braverman resigned – technically over a security breach, but much more realistically over the fact the government was now pushing for more migrants to fill skills gaps. Her letter to Truss was clearly more about auditioning for a future leadership election than anything else, and signalled a clear break between Truss and the Brexity right of the party. Braverman had run against Truss over the summer leadership election and then supported her, giving her the crucial boost she needed to get to the run off with Rishi Sunak.

This huge right wing bloc, who got behind Truss to stop Sunak, were clearly unhappy. The tax policy some of them had pushed was abandoned.

But then, just because the day would not stop, along came a parliamentary vote on fracking, set up by Labour to embarrass the Tories. The Conservatives’ 2019 manifesto (that was the last election) banned fracking for the foreseeable future, but Truss campaigned on allowing it again.

The Tories let it be known that this vote would be treated as a confidence vote, meaning if the Tories lost it the King would need to step in and call a general election. It also means that all Tory members who voted against their party would “lose the whip” – essentially suspending them from the party.

Yet several prominent Tory MPs said they would vote against the government, thanks – after all they were just upholding the manifesto they were elected on!

As the vote was happening true chaos engulfed the House. The energy minister said it wasn’t actually a confidence vote after all. Both whips were reported to have resigned, with one exclaiming “I don’t give a fuck any more”. There was reportedly actual manhandling of MPs to get them into the right voting lobby, although this has been strenuously denied. Eventually the PM said the whips hadn’t actually resigned.

That was all in one day?

Yes. It got so bad Downing Street issued a statement at 1.30am.

But she held strong until the afternoon on Thursday?

That’s right. As Thursday got going a growing group of Tory MPs called on her to resign. Eventually the chair of the 1922 committee – basically the leader of the backbench party – went to meet her, likely to tell her it was over, and if she fought it things would get even uglier.

Does this mean months without a PM again?

Not this time. The last leadership election ran from early July to September, with several parliamentary rounds and then a long time for party members to get a say and meet the candidates. This time it will all be over by next Friday, or possibly by Monday.

How will the replacement be picked? Are we in for a huge range of candidates again?

Probably not.

At the last leadership election, a candidate needed just 20 fellow MPs to nominate them, which isn’t that hard in a party of 357 MPs. Seven candidates cleared that bar, and were progressively winnowed down in several rounds of voting.

This time the bar is 100 MPs pledging support by Monday morning (Monday night NZT). No MP reached that high on the first round last time: front runner Rishi Sunak got 88, while Truss got just 50.

If there are more than two candidates left there would then be a round of voting among the party’s MPs to narrow it down to two. If there are two, an “indicative vote” will be held by MPs but then the final say is handed over to party members in an online vote.

What if only one candidate reaches 100 nominations?

Many Tories will be hoping for this outcome, a bloodless transition with no pesky members being involved. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to happen.

Why such a change since the last one?

The Tories know the country will not put up with another months-long period of stasis while a new PM is selected by 80,000 or so members.

This indicative vote will be used to show the membership who the party’s MPs can actually work with and who it might revolt against. Remember, the parliamentary party far preferred Sunak to Truss.

And the 100 rule is widely interpreted as a way to eliminate people the members might like but most MPs would hate – like, say, the last prime minister.

Could Boris really come back?

Everything and anything is possible.

By all reports, he wants the job again. To many in the party, the personal chaos he presided over, which saw the Tories mostly just a single-digit behind Labour in the polls, might seem preferable to the national chaos Truss has presided over, which has seen thousands of people lose their potential mortgages and the Bank of England step in to save the pension funds.

And lots of Tory members would want him back. But it’s not certain he would clear that 100 MP bar. The reasons Johnson was forced out have not gone away: the wider public is still disgusted with the fact he broke lockdown rules for parties, and his colleagues are sick of the many times they went out to defend him in broadcast interviews with lines that later turned out to be untrue. Most people don’t like lying, but people really don’t like lying on someone else’s behalf, especially if they get found out.

Who are the other contenders?

Penny Mordant came third in the last race, but led many polls of members for a time. She is an affable MP without much heavy-hitting cabinet experience, and was demoted by Boris Johnson. Several colleagues called her lazy during the leadership race, but her initials are the same as the phrase “Prime Minister”, which is pretty good. Plus on camera she seems quite ordinary and friendly. She voted for Brexit.

Rishi Sunak hasn’t declared but has a lot of declared support already, and is the bookies’ favourite. Sunak was chancellor during Covid-19 and ran against Truss in the leadership race, winning among his fellow MPs but losing to the members. He spent the entire campaign warning that Truss’ policies of unfounded tax cuts would end in, well, this. He voted for Brexit.

Ben Wallace is the current defence secretary and is very popular inside the party, looking every bit the former soldier. But it’s not really clear that he actually wants the job given he didn’t run last time. Wallace voted Remain.

Kemi Badenoch made waves during the leadership election after a short career as a relatively junior minister and is positioned strongly on the social right. She supported Brexit.

Suella Braverman. Remember like 1000 words ago, the home secretary who resigned? Her! She is also on the right of the party. Prior to the Boris drama she was attorney general so has some serious experience. She supported Brexit.

Who is going to win?

I don’t know, man. Probably Rishi Sunak? But maybe Boris or Penny? The bookies have those three ahead.

Shouldn’t there be a general election?

On a conditional level, the country elected the Conservative Party to government for a five-year term in 2019, not Boris Johnson. The party has a right to change its leader as much as it wants during that period.

On a political level? Many in the country feel they have been force fed a programme they never voted for and desperately want to toss these guys out. Yet there is almost no incentive for the Tories to go to the people. After all, most of them would lose their jobs if they did. However one of the core issues for Truss was that she didn’t really have a mandate, so there is a chance a new leader would feel they really did need a new mandate.

It sure makes one think New Zealand’s three-year term might not be such a bad idea.

Why is the UK like this?

The 2016 Brexit vote seemed to fundamentally break something in the country’s stable constitutional order, and it has faced huge disruption ever since.

Governments ever since have wanted to deliver something impossible: A break from the European Union that wouldn’t hurt the economy or break up the UK itself, but would also deliver all the freedom from EU rules that Brexit promised.

Chaos has defined the country’s politics since. The one man – Johnson – who seemed able to at least get his entire party onboard with Brexit was so personally chaotic the party nevertheless had to get rid of him.

Or you can blame the anti-growth coalition. Or general declinism. Or the fact that most governments in power for this many years (since 2010!) just end up with their contradictions overtaking unity. Or maybe it was the partisan press. One thing is for sure – there may be calm waters for the country somewhere in the future, but we aren’t there yet.