Those who rush to condemn the Auckland visit of Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte display their ignorance of the nation’s complicated history and nuanced current situation, says Cameron Walker.

December 2017: The author has added a postscript to this article. Scroll to end to read

Since Rodrigo Duterte was elected president of the Philippines in May, the country – for the first time in decades – appears regularly the World section of New Zealand media. Before his election few outside of the Philippines would have known any Filipino swear words, or even the name of the country’s president.

Many media stories have portrayed him as a foul mouthed killer and dictator in waiting. Media coverage of Duterte’s short visit to Auckland this week continued this theme.

Larry Williams on Newstalk ZB described Duterte as a “nasty, nasty piece of work”. Williams asked Michael Bott, a prominent New Zealand human rights lawyer, if Duterte should be banned, to which he replied “I don’t think he has any place in New Zealand”. Bott even drew parallels between Murray McCully meeting Duterte and Neville Chamberlain appeasing Hitler.

Human rights violations in the Philippines, including the recent wave of drug suspect killings, are of huge concern to me. As part of the group Auckland Philippines Solidarity I have written many press releases condemning killings by the security services, helped organise speaking tours of Philippine human rights advocates to New Zealand and spent time with leading human rights organisations in the Philippines.

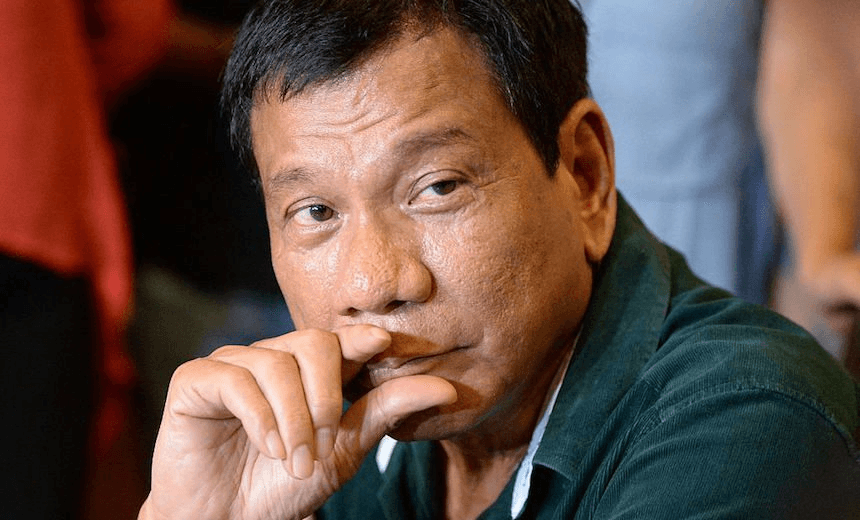

(Photo: NOEL CELIS/AFP/Getty Images)

I should be happy the issue of extrajudicial killings in the Philippines is finally being tackled regularly by the New Zealand media. However, attempts to paint Duterte as an evil monster worthy of pariah status ignores the long history of state death squads in the Philippines. Death squad killings were rampant under the Marcos dictatorship (1972-1986) and have continued in varying degrees under every president since. They have targeted both political activists and alleged criminals.

Of all the Philippine presidents since 1986, only Duterte has been singled out for such extreme international condemnation. This risks letting other political factions responsible for serious human rights abuses off the hook.

The exaggerated criticism of Duterte fails to acknowledge some positive developments under his leadership. His administration has restarted peace talks with the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), which represents the Communist Party of the Philippines and its armed wing, the New People’s Army (CPP/NPA), in talks with the government. On this issue Duterte may prove to be less bloody than his predecessors.

Since 1969 the CPP/NPA has been fighting an armed struggle against the Philippine government. The conflict has cost tens of thousands of lives. During the Arroyo (2001-2010) and Aquino administrations (2010-2016), the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and allied paramilitaries launched a brutal counter insurgency campaign against the movement, targetting armed rebels and civilians a like.

Trade unionists, student activists, human rights workers, indigenous people in isolated rural villages and clergy were accused of being civilian sympathisers of the Communists and subject to serious human rights abuses by state forces, including murder by gunmen riding tandem on motorcycles. Some activists were kidnapped and have never been seen since.

(Photo: MANMAN DEJETO/AFP/Getty Images)

In contrast, in the same period as Mayor of Davao City, Duterte preferred a more conciliatory approach to the communist conflict. When I was in Davao in 2012 I interviewed a former NPA fighter who had been critically injured in a clash with the AFP in a rural area. Duterte organised a private jet to fly her to Davao to receive the specialist medical attention she required. On other occasions he also facilitated the release of soldiers and police captured by the NPA. His actions certainly resulted in fewer lives lost on both sides.

Many in the Philippines hope Duterte will continue this conciliatory approach throughout his Presidency and maybe even achieve a lasting peaceful resolution of the conflict. Both the Philippine government and the NPA have currently declared a ceasefire. The peace talks, facilitated by the government of Norway, are not only covering issues such as amnesty for political prisoners, but also the wider socio-economic issues, including poverty and the wide gap between rich and poor, which sparked the conflict in the first place.

Philippine activist groups, including unions, environmental groups and human rights activists held a conference last month to mark Duterte’s first 100 days in office. They praised Duterte for charting an independent foreign policy from the US, reopening peace talks and supporting land reform. Yet they were strongly critical of extrajudicial killings of drug suspects and other authoritarian measures. Philippine human rights groups continue to criticise the government for failing to release all political prisoners and recently for allowing the body of Ferdinand Marcos to be reburied in the Libingan ng mga Bayani, a cemetery in Manila meant to honour former military servicemen.

New Zealanders should raise concerns about human rights in the Philippines.

However, painting Duterte as an evil monster is counterproductive and fails to take into the account the complexities of the political situation in the Philippines.

New Zealand human rights advocates would be better to take the nuanced approach of their counterparts in the Philippines. Condemn the bad and support the good. Not taking into account the views of those actually on the ground campaigning against death squad killings just reinforces the ugly colonial view that people in the Third World are hopeless and need saving.

Postscript December 2017

Sadly the ceasefire between government forces and the NPA did not hold for long. In February the NPA ended its ceasefire claiming government troops were still attacking its base areas. The government soon reciprocated by ending its ceasefire.

On November 23 2017 Duterte issued Proclamation No. 360 s. 2017 which officially terminated the peace talks with the National Democratic Front, the political representatives of the CPP/NPA.

The President has encouraged the AFP to “flatten the hills” where NPA rebels are present, without regard for civilian casualties. He also threatened to bomb schools, run by the indigenous Lumad people of Mindanao, deemed left wing friendly by the military. Recently a number of political activists from progressive organisations have been murdered by unidentified gunmen.

Activist groups in the Philippines have also expressed anger at the failure of Duterte to uphold his promises of land reform, independence from US foreign policy and ending the casualisation of the Filipino labour market.