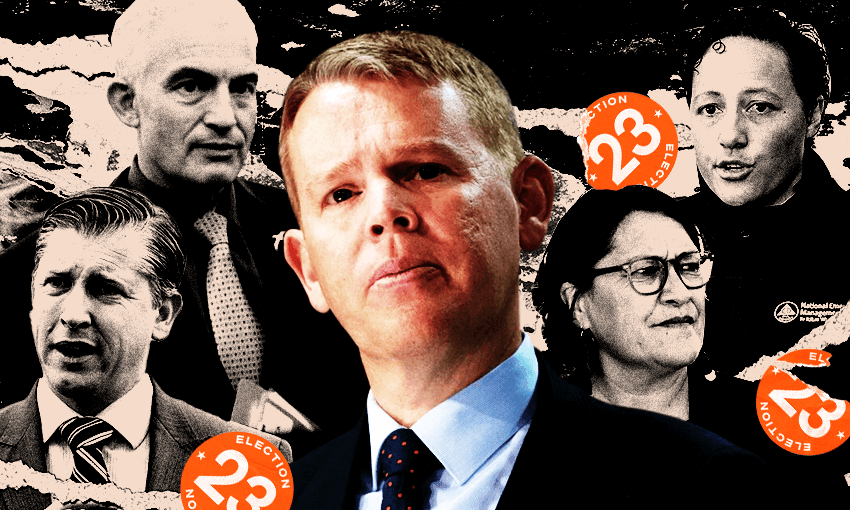

As his contemporaries flounder, the prime minister finds himself in a lonely position regardless of the election result, writes Mad Chapman.

At first glance, Ardern plotted her resignation perfectly. She planted the seed with close colleagues and friends Grant Robertson and Chris Hipkins before Christmas (but didn’t inform the rest of caucus until moments before her public announcement), and following her resignation, and Robertson ruling himself out, there was no public contest for the role. Kiri Allan and Michael Wood were both floated by commentators as possible contenders but Hipkins quickly emerged as the unanimous choice, and he immediately got stuck in with the Auckland Anniversary flood emergency, with new deputy Carmel Sepuloni alongside.

Ardern left office and Hipkins moved in, barely disturbing the waters.

And in the careful orchestration of the leadership takeover, it seems everyone else was forgotten.

Kiri Allan, for some years considered a potential successor to Ardern, announced on Tuesday that she wouldn’t be contesting the 2023 election after being arrested for careless driving and failing to accompany a police officer following a Sunday night car crash. Allan cited a personal relationship break-up (she had previously described herself as “heartbroken”) and ongoing mental health struggles as context for the incident. She promptly vacated her ministerial portfolios and is currently at home on the East Coast.

Allan is the fourth minister to depart in controversial circumstances since Ardern herself resigned as prime minister in January. Labour in 2023 is a case study in workplace fatigue and turnover contagion. After six years in power and three years in a global pandemic, Labour’s people are tired. And tiredness begets mistakes.

Ardern resigned after leading the country through a terrorist attack, multiple natural disasters and a global pandemic that resulted in an unprecedented level of vitriol being directed both at the government and her personally. A common response to her resignation was “sure, you must be tired and need a break”. There’s no question that Ardern personally wore the weight of most of the events during her nearly two terms. But every minister’s workload and public exposure increased exponentially. Allan also spoke candidly in November of the growing aggression from the public towards politicians. With Ardern removing herself as the lightning rod for public scrutiny, that exposure would only grow.

When Hipkins became prime minister, there was the air of new energy that comes with any new leader. Hipkins was fresh and a high-performing minister. It was going to be a new era with new people and new ideas. Except that didn’t happen at all.

Because while Ardern was the most visible politician working within a highly stressful environment for five years, everyone else in government was in the same boat, paddling just as hard with all of Ardern’s policies and promises at their feet. And when Ardern handed the steer to Hipkins, those same people were still paddling the same boat. Instead of introducing new ideas, Hipkins simply unloaded some of Ardern’s. Hardly a move that would inspire his colleagues to dig deep into their reserves.

Have you ever worked somewhere and had one colleague that kept you sane? And every week you’d mutter something along the lines of “if you ever quit, I would quit too”? As the effects of the pandemic stretched into a second and third (and now fourth) year, workers all over the country were reaching breaking point and those thoughts became a constant. For many Aucklanders, it resulted in a 2021 lockdown breakdown. For everyone, it was strained relationships and a feeling of treading water. (Hipkins himself separated from his wife some time in the past year.) But unlike politicians, many of us were able to have our breakdowns and breakups in private, hopefully with an understanding employer providing space and support.

Ardern resigned before it could happen to her (at least publicly). And Robertson, despite decades of ambition, decided he didn’t have it in him either. Once Ardern left, others couldn’t. Poto Williams and Aupito William Sio had already announced their retirements from politics. A week after Ardern’s resignation, Robertson announced he’d be running list-only in 2023, allowing for no byelection if he chose to resign following a potential Labour loss. For the next wave of ministers (Hipkins, Woods, Wood, Allan, Nash), now was not the time to step back. The unstated assumption was that those newer to parliament would still have the energy, despite the overwhelming stress of this term.

Nash, Wood and Allan didn’t resign entirely of their own accord. But it’s worth considering how many of Labour’s senior ministers, who worked alongside Ardern through all the stress and trauma listed above, simply don’t really want to be doing this any more. Meka Whaitiri certainly didn’t want to do it any more when she defected to te Pāti Māori.

The job that Ardern left couldn’t have looked less appealing. There would have been ministers, Allan included, who felt that being presented with the job of prime minister after what they’d just been through was like being offered a gym membership after nearly starving to death.

And so it was Hipkins taking over the load, chucking out policy cargo and urging his inherited ministers to keep paddling. Instead, they’ve done the opposite. Whether through negligence, arrogance, or simply mental exhaustion, Hipkins’ team of ministers has fallen around him. And with each resignation, the load on those still standing increases. It’s a snowball effect that will become hard to escape for the few ministers left holding a now comical number of portfolios.

Commentators this week have confidently predicted that Allan’s downfall has secured a National win on election day. The campaign hasn’t even started and polling shows it’s anyone’s election to win, but Hipkins has found himself sitting on an optical illusion pedestal. He took the top job with a secure cabinet around him and now, with ministers falling away, he’s accidentally risen to be alone on a plinth.

Much as the likes of Allan may have felt compelled to stay on after the omnipresent Ardern stepped away – with that feeling only amplifying as Nash and Wood each fell, leaving some of their portfolios to her – who will now be required to step up? Megan Woods has been through the housing wringer and kept a low profile of late. Jan Tinetti is waiting for people to forget about her sojourn to the privileges committee. Andrew Little has been there, done that. Damien O’Connor has been in parliament longer than I’ve been alive (literally).

The younger (or newer) ministers now taking on outsized responsibilities are Kieran McAnulty (five portfolios), Priyanca Radhakrishnan (three portfolios, associate minister for two others), Ginny Anderson (five portfolios, associate minister for one other), Barbara Edmonds (four portfolios, associate minister for three others) and most recently Willow-Jean Prime (two portfolios, associate minister for three others).

Maybe they’ve all managed to refuel and prepare for their sudden responsibilities amid the departures of close colleagues, but a more likely scenario is a growing sense of responsibility and obligation among a crop of ministers that would otherwise have likely developed into senior leadership within the party. Outside of anything else, it’s hard to imagine a new minister across multiple portfolios being very successful in any of them. So until the election (still three months away), every Labour minister’s main job will simply be to survive.

Hipkins will stay as leader because there really are no other options. But barring a star turn from Sepuloni this campaign, it’s going to be lonely up on that pedestal no matter what happens on election night.