Following the launch of debut game Dr Grordbort’s Invaders, Weta Workshop’s game division invited Baz Macdonald in to discuss the project’s long development and to explore what the future holds for mixed reality gaming.

Stepping into Weta Gameshop, the development studio at Weta Workshop, the first thing you see is a gigantic Edwardian-era fireplace decorated with the busts of steampunk characters and models of quirky, slightly sinister robots, flanked by the mounted heads of outlandish alien creatures.

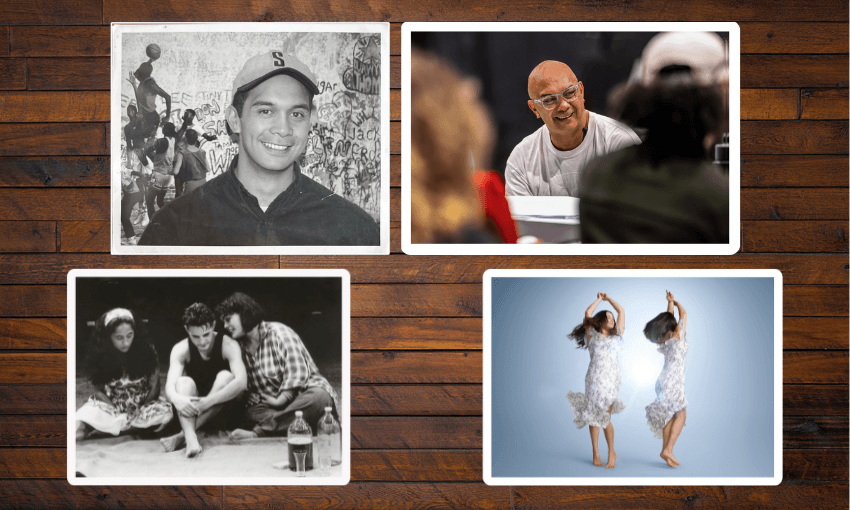

It’s a scene taken directly from the universe of Dr Grordbort, a steampunk meets space opera conceived and developed for over a decade by Gameshop game director Greg Broadmore, who greets me at the studio with a fierce handshake and a warm smile beneath his enormous beard. As a 17-year veteran of Weta Workshop, he’s part of an old guard who came through the Lord of the Rings years and into a new era of Weta – one in which it is now involved in everything from props design to museum exhibitions to game development.

As shown by their Gallipolli: The Scale of War exhibit at Te Papa, Weta Workshop has never been content to do things traditionally. With every new venture, Weta seems determined to find the most out-of-the-box way of exploring that field; their game development studio is a perfect example.

In jumping into the video game industry, most developers would be content to develop a game for an existing platform like the PS4, Xbox One or PC. But not Broadmore and the Weta team. They have instead been developing a title for a ground-breaking new mixed reality headset which allows you to turn your own living room into the setting for a robot invasion.

Broadmore leads me to a boardroom lined with panels from Dr Grordbort comics. An avid gamer himself, he explains that while Dr Grordbort started as a series of collectibles and comics, he always dreamed of bringing the world to life in a game. It was with this mindset that he and Weta Workshop CEO and Co-founder, Richard Taylor began conversations with film studios and game publishers around the world about the idea of a Dr Grordbort video game and feature film. That is when they met Rony Abovitz, the founder and CEO of Magic Leap.

Abovitz was working with Weta’s film division when he mentioned his idea for an augmented reality device – an idea which would eventually become Magic Leap. This was eight years ago, long before the device and its innovations had been created, or Magic Leap became a Silicon Valley darling, even before the current VR evolution had taken off with Oculus and PSVR.

“When [Abovitz] first told me that he was going to make these goggles that would allow you to hold a ray gun in your hand and shoot enemies and have this adventure in your house – I was thinking ‘OK! You’re crazy’,” Broadmore says, “because the last VR/AR I could remember were in the arcades in the ’80s – which were terrible experiences.

“He was describing something which was pure science fiction.”

But it was science fiction that soon captured the hearts and minds of Silicon Valley. Magic Leap went from operating in secret in 2014 to being valued at US$4.5 billion in 2016 after a series of increasingly gargantuan funding rounds. Weta was right there from the beginning.

“[Abovitz] flew me over for meetings when there was only three or four of them in the company.” Magic Leap now has over 1700 employees registered on LinkedIn.

Over the last seven years Weta Workshop has slowly been building up its game division while doing the research and development necessary to discover what works in this mixed-reality medium. In the process, it went from just three people to over 50 employees at the peak of development. It is only in the last two years, with Magic Leap approaching release, that Weta took on full-scale development of what would become Dr Grordbort’s Invaders.

Invaders brings the Dr Grordbort universe to life in your own home. With the headset on, you become a soldier fighting off an invasion of robots who appear through portholes in your floor and walls. Using an arsenal of ray guns, you fight off waves of these robots in missions that delve deeper and deeper into the world and lore of the Dr Grordbort universe.

After years of development, in August the Magic Leap One was launched into the US market. Then in October, at the annual Magic Leap conference, it was announced that Invaders was going live that day.

The response to the launch was underwhelming, especially in the face of the years of hype and the amount of funding Magic Leap received from industry leaders like Google. At launch, Scott Stein from CNET wrote that his initial experience “didn’t blow me away, despite Magic Leap’s promises”. However many tech writers welcomed the Magic Leap as an exciting, if flawed, precursor of entertainment technology to come. Joanna Stern of The Wall Street Journal wrote that the Magic Leap One was “an inspiring glimpse at the future of our interaction with technology, and each other”.

Broadmore says the team always saw the initial launch as a sort of “early access” period. The hype build for the device was necessary, he says, because the biggest obstacle with any new tech is getting people interested in the first place.

“Magic Leap has the challenge of convincing the world that this medium – spatial-computing mixed reality – is even a thing. I mean, most people don’t even know it exists. Magic Leap had to hype to get where it got. You don’t get to build anything revolutionary by going ‘it will be OK’. You have to back yourself, and you might end up building up unrealistic expectations in people’s minds.”

It has been frustrating to see the device criticised for its rough edges by the tech press, Broadmore says, especially when on the next page they are heaping praise on devices such as new smart phones.

“One of those things has been around for ten years and is just polishing the same thing and this other thing is categorically, stratospherically, in a new realm. [Magic Leap] might have rough edges, but it is actually a revolution.”

Despite the muted reaction to the Magic Leap One, Invaders itself has been widely heralded as a demonstration of the possibilities of mixed reality. “If there’s one experience meant to show the Magic Leap One’s potential, it’s Dr. Grordbort’s Invaders,” wrote CNET’s Patrick Holland. “This game is to Magic Leap what Super Mario Brothers is to Nintendo. It’s beautifully designed, intuitive to control and a blast to play.”

Because of the close partnership between Magic Leap and Weta’s game wing, the companies share the short-term goal of proliferating this technology and its potential. In fact, the companies and their goals are even more intimately integrated than it seems from the outside, with 70% of the game division being employed by Weta Workshop and 30% by Magic Leap. Primarily, the Magic Leap staff are engineers who need frequent access to the proprietary Magic Leap codebase.

One of the biggest obstacles to AR uptake is getting people to understand the experience without actually trying the device themselves. As such, Weta and Magic Leap are planning a campaign of demos around the US in 2019. Both companies are clearly in this for the long haul; as for Broadmore, he’s a true evangelist of the medium and the potential it holds for the future of gaming – and of entertainment itself. He doesn’t see a mainstream adoption of mixed-reality as a matter of if, but as a matter of when.

Screens are a fantastic medium, he says, but the concept of interacting with them is abstract – you need to teach people how to do it. “If you hand a keyboard and mouse, or even a controller to someone who doesn’t play games, it is like asking them to learn to drive a car in order to drive a person. But why should you have to learn to operate a human being? You already know how to operate a human being! That is the beauty of mixed-reality.”

Just as Wii did with games like tennis and bowling, mixed reality removes this layer of abstraction and allows people to interact with game worlds through nothing more than their own innate motor skills. This accessibility means there is a real potential for mainstream adoption of this technology by anyone and everyone, Broadmore says. “I’ve seen so many older people play the game – and they get it straight away.”

Broadmore talks passionately about the emerging potential of mixed reality. He paints a picture of a future in which AR systems could change the texture of the world around you, transporting you to different worlds and realities within the physical parameters of your everyday environment. But this technology doesn’t need to be confined to your home, he says – there is potential for the gamification of the entire world through devices like Magic Leap. He described a technical test in which an engineer programmed coins to generate within his headset on a beach in California, and then drove around picking them up, Mario Kart-style.

With Invaders launched, Broadmore says the studio has moved from working exclusively on it to developing three new games. Though these projects are too early to announce, Broadmore hints they are interested in exploring how mixed-reality could integrate “shared experiences” – AKA multiplayer – in the Dr. Grordbort universe.

As to whether the studio will branch into more traditional video game development, Broadmore says they are independent enough that they could develop independently from Magic Leap if they chose to.

The projects the game division is working on in the short to medium term will also be in the Dr Grordbort universe – which Broadmore says they have “barely begun to explore” in Invaders. But with one of the core tenets of the studio being the cultivation of new ideas, he says he can see Gameshop moving into new IP for future projects.

“I want to go as wide and crazy as possible – so making your own IP is where it’s at.”